-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

How Canada is fighting Hitler

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: How Canada is fighting Hitler

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

Beating her plowshares into swords, our neighbor pours man and materials into war

WITH less than one tenth the man-

power of the United States, Canada

has already thrown a decisive and

startling volume of military and indus-

trial power into the battle against Hitler.

Its army of 400,000, of whom 100,000 are in

England, is the largest in its history. Its

planes and pilots, which when they were few

fought savagely in the Battle of Britain,

today number more than 100,000 Air Force

personnel and thousands of planes. The

Navy, expanded more than ten times, main-

tains vigilant watch over the North Atlan-

tic. And finally, Canadian industry, rela-

tively small in 1939, today furnishes most

of the equipment for the Dominion’s own

armed forces, and within six months will

reach its production peak, a full year ahead

of the United States.

The transformation of the Dominion’s

economy from agricultural to industrial has

been a modern machine-age miracle. A na-

tion of farmers, trappers, miners, and

traders has turned into a nation of soldiers

and factory workers. During this fiscal year,

Canada is making a literal gift of 1% billion

dollars in war equipment to the Empire and

fully half of the Empire's air strength will

eventually come from the Dominion—two

reasons why every Canadian is giving up

almost one half of his income in taxes.

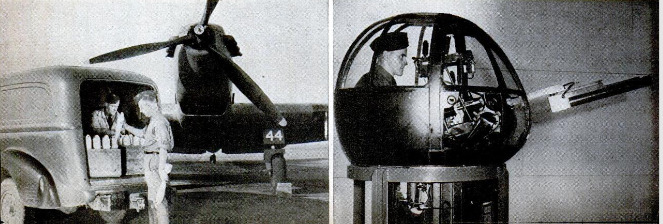

As aviation-minded as any people on

earth, the Canadians have made their most

conspicuous war effort in the air. At the

beginning of the war, the Dominion’s air-

craft industry was very small. This year

its production has approached 200 planes a

month—bombers, fighters, and trainers—

and it still is increasing.

But producing planes is not enough. Men

must be trained to man them. And when

the Nazis invaded Poland the Royal Ca-

nadian Air Force consisted of some 4,500

flyers and groundmen. Today its strength,

including the civilian employees, is close to

100,000 and still is growing rapidly.

Head man of the air effort is C. G. “Chub-

by” Power, Minister of National Defense

for Air. One of the realists who face the

fact that this war is going to be won the

hard way, Power says that before it is

over half of the Empire's airmen will be

Canadians.

The R.C.A.F., a separate organization

trained to codperate with the army and the

navy, has an Overseas War Establishment,

a Home War Establishment, and—of highest

long-range importance—is in charge of the

British Commonwealth Air Training Plan.

The Air Training Plan, started three

months after the war began, was launched

to train air crews from all over the Empire

in Canada. Schools had to be built, flying

fields prepared, training planes purchased

in the United States because Canada had no

production of its own.

Before the project could get under way,

the German blitzkrieg swept across France,

and Canada rushed every plane and airman

available overseas for the defense of Brit-

ain. Despite this delay, the program was

pressed and by the fall of 1940 airmen were

being turned out, trained and ready to fight,

a whole year ahead of schedule!

It was a job that took a lot of doing.

More than 100 air fields were prepared, 90

R.C.A.F. schools and some 40 auxiliary es-

tablishments were opened, with the Cana-

dian Government paying the bills for all

this construction.

Getting recruits was the easiest part of

the job—every youth in Canada wants to be

an airman. Eighty percent of the men

trained are Canadians (including the ten or

twelve percent of Americans who wear the

letters “U.S.A.” on their shoulder tabs), ten

percent are Australians, eight percent New

Zealanders and two percent Britons. South

Africa and India have their own air-train-

ing systems.

Students first are classified on their capa-

bilities and aptitudes into the three air

“trades’—pilot, observer, and radio opera-

tor. All are gunners as well.

Initial training is a five-week course at a

manning depot, where the recruit learns in-

fantry drill and the ways of the air service,

and takes part in conditioning sport. The

radio operators next go to a wireless school

for a 20-week course, then move on to an

air-gunnery school for a month.

Pilot and observer candidates are sent to

an initial training school for five weeks of

‘mathematics, armament and map reading,

and on-the-ground flight instruction in Link

trainers. Observers get 14 weeks in an air

observers’ school studying navigation, pho-

tography, and aerial reconnaissance, fol

lowed by six weeks at a bombing and gun-

nery school, topped off with another four

weeks at an air-navigation school.

The pilot candidates move directly to one

of the 26 elementary flying training schools

which are operated by civilian aviation com-

panies under R.C.A.F. supervision. The 48-

day elementary course comprises theoreti-

cal, ground, and flight instruction. First

solo flight comes after ten or twelve hours

of dual instruction, and at the end of the

course the student has had about 50 hours in

the air, half of it solo. Next is ten weeks

studying aviation theory, maintenance work,

advanced, night and instru-

ment flying, cross-country

Davigation, and air gunnery

at one of the 16 service flying

training schools.

Twenty-two weeks after

starting at the initial train-

ing school, the pilot who

passes the course has his

wings—the observer and ra-

dio operator the _single-

winged insignia of their

“trades.” Fast going, but

this essential wartime speed

hasn't been achieved at the

cost of sacrificing lives. Al-

though some of the schools

send planes up as rapidly as

every 25 seconds from dawn

to dark, up to September there

had been only 31 fatal train-

ing accidents. That the train-

ing is thorough as well as

rapid is shown in frequent

assignment of a pilot to his

first service job—flying a

bomber across the Atlantic!

Very soon after they re-

ceive their wings, most of the

air-crew men are sent over-

seas, for final operational

training in fighter aircraft.

Most Canadians are con-

vinced that in this war air

power is all-important—both

to disrupt German industrial

effort and to soften up Ger-

man civilian morale by big-

scale bombing, and to over-

come the Luftwaffe in the

air as an essential prelude to

offensive action on land.

And Canada is ready for

land action, too. Since the

war started, the Dominion

has raised its army from less

than 60,000 regulars and mi-

litiamen to well over 400,000,

about 230,000 volunteers for

the duration to fight any-

where, and 170,000 in a re-

serve army. Three divisions,

over 100,000 in all, are serv-

ing in Britain under Lieut.

Gen. A. G. L. McNaughton,

Canada’s top soldier. An

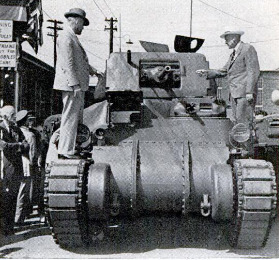

armored division has been

equipped with Canadian-built

tanks—part of the new indus-

trial output—and probably

now is on its way overseas.

A Canadian infantry divi-

sion is a hard-hitting fighting

unit: three brigades of in-

fantry, a machine-gun battalion, a cavalry

regiment mechanized to fight in light tanks

and armored cars, three regiments of field

artillery with 72 25-pounder guns (which

are about the same caliber as U.S. 105s),

an antitank regiment with 48 two-pounder

guns, and auxiliary troops. On paper it also

has a tank brigade, but only one of these is

in actual service and other units will be

formed as rapidly as factories turn out the

armored vehicles.

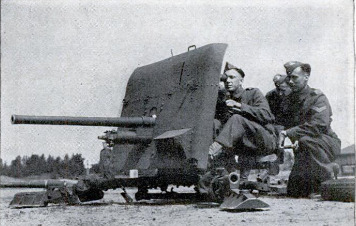

A highly important piece of equipment is

the Canadian-built Universal carrier pow-

ered by a Ford V8 engine—a fast, agile,

lightly armored tractor on whose mounts a

Bren light machine gun

may be used either as

an antiaircraft weapon

or against ground

troops. It also carries

a 55 caliber antitank

magazine rifle which

can be fired either from

the vehicle or on the

ground.

In battle, the car-

riers’ job is to get the

Bren guns and their

crews into action in a

hurry and with mini-

mum casualties; that

done, they scoot for the

nearest cover. On

marches they are used

for general transportation like any tractors.

The Bren gun is the principal infantry

weapon; each section of nine men has one.

Most of the men are armed with ten-shot

bolt-action Lee-Enfield rifles, and carry

hand grenades. Two-inch mortars also are

used, and every man must know how to

handle every infantry weapon.

In the camps which I visited the brown

faces under the tin hats looked rather more

serious than our soldiers’ faces do—several

younger officers were on “24-hour notice” to

report at embarkation depots. The troops

were as well cared for as ours, but it was

plain that less money had been spent on

nonessentials. The food was excellent. So

were the bathing and sanitary arrange-

ments. Recreational facilities were rough-

and-ready but adequate. Discipline was

noticeably good and obviously not harsh.

Recently, recruiting for the Active Serv-

ice Army has slowed down, but army offi-

cers ‘believe this lack of enthusiasm is due

to the Canadian Corps’ bad luck in not get-

ting into any fighting overseas. As soon as

the shooting starts, they think, there will be

a flood of volunteers. They back up their

opinion by pointing out that the air force

and navy, which are fighting now, have no

recruiting problems.

The navy, is fighting, though little official

information is released. When the war

started, Canada’s navy consisted of 13 ships

and 3,600 men. Now there are over 20,000

men, all of them volunteers, manning more

than 200 warcraft including destroyers,

armed merchant cruisers, and the new cor-

vettes—destroyerlike vessels used for con-

voy and patrol service—minesweepers, con-

verted yachts, and other small antisubma-

rine craft. By next March there will be more

than 400 ships and 27,000 men in the service.

The Canadian Navy, up to early October,

had a long casualty list, with 420 dead.

To furnish adequate food, clothing, and

materiel to her armed

forces, Canada has

made every possible use

of machinery and man-

power. Clarence Deca-

tur Howe, the Ameri-

can-born Minister of

Munitions and Sup-

plies, has directed the

gigantic task. Except

for one plant which had

just started to produce

Bren guns, the coun-

try had no munitions

industry when the war

began. Aircraft pro-

duction was insignifi-

cant, and only 1,500

workers were employed

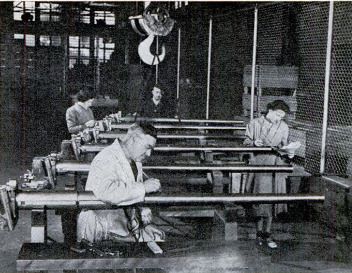

in shipyards. Today, following a $500,000,-

000 investment in new equipment, a Gov-

ernment training program, and a subcon-

tracting system which allows not a single

machine tool to be idle, 111% million people

have almost reached their potential limit of

production.

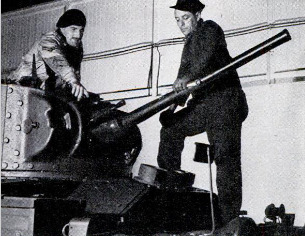

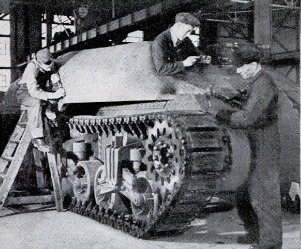

I was allowed to see a few of the signifi-

cant items which compose this huge pattern.

Infantry tanks of British design were roll-

ing off the production line in a former rail-

road shop. Another plant was making 28-

ton cruiser tanks of Canadian design, with

cast-steel welded armor which needs no

rivets, Canada’s top scientists and research

men were working on war tasks in the lab-

oratories of the National Research Council.

Thousands of women and girls made Bren

guns in an Ontario plant which has the

largest output of any automatic gun plant

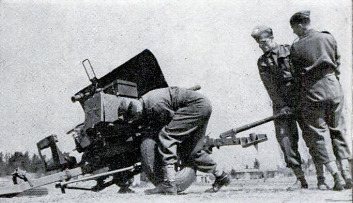

in the world. Bofors antiaircraft guns were

produced in an elevator factory—by the

same men who used to build elevators,

The encouraging fact is that today the

people of Canada are convinced that they

are doing their best, and that their best will

be good enough. Winston Churchill himself

is authority for their firm belief that without

Canada’s war effort the resistance of the

British Empire could not be maintained.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Arthur Grahame (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

Eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1942-01

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

96-100

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

Popular Science Monthly, v. 140, n. 1, 1942

Popular Science Monthly, v. 140, n. 1, 1942