-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Americans take to tanks...

like ducks to water

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: Americans take to tanks...

like ducks to water

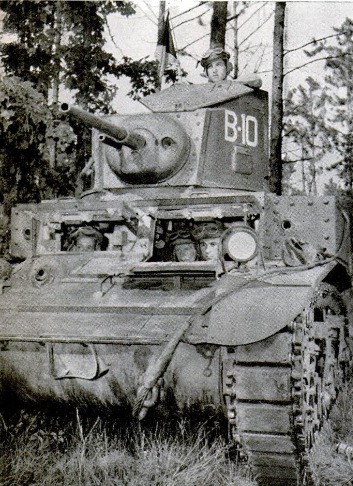

THOSE folks who have been squawking about

bad morale in the Army would do well to visit

some outfit of the 2nd Armored Division. It would

reassure them, for instance, to come up with the

2nd Battalion, 66th Armored Regiment, bivouack-

ing in the piney woods down south. Certainly it

would do their spirits good to meet Private

(Specialist 3rd Class) Jaillet.

Blackie Jaillet had been in the Army eight

months. His pay had been raised three times and

was in immediate prospect of going up another

ten bucks. He had gone through

three months of intensive schooling

with gas engines. Then, just before

his twenty-second birthday, he had

been made commander-driver of a

light tank. Blackie wasn't bellyach-

ing at all.

It was raining the day we met him.

It had been raining for several days,

and the Louisiana forest was like a

steam bath. The primitive back

roads, through which the column had

moved in yesterday, had been

whipped by the trucks and tanks in-

to a mere succession of hog wal-

lows. Later, when Blackie drove us

through those roads in his tank——pitching,

tossing, spray flying, into the ditch and out

—it was just like riding the bow of a sea

skiff into a heavy swell. Coming in with a

civilian car it was tougher going, passing

the streaming trucks and half-tracks, but

there was always a jeep to push us out of

the grip of General Mud.

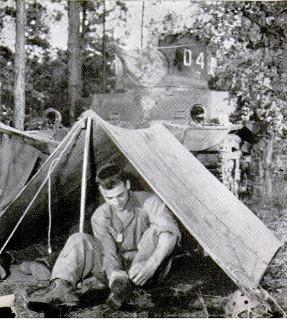

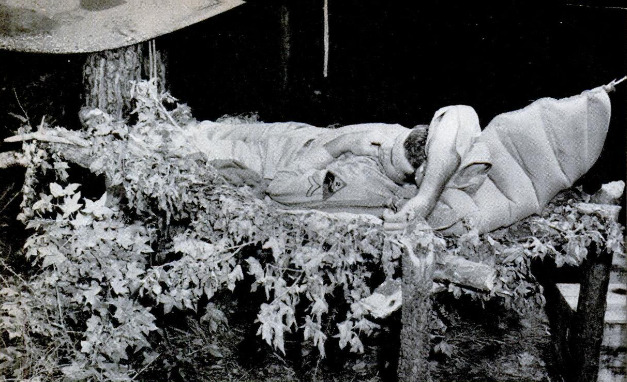

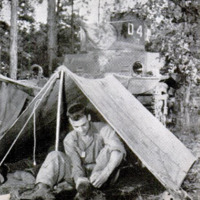

Except for the crowded roads, the woods

seemed almost unpopulated. The 66th was

hidden back in the brush, tanks snuggled

under the shrubbery, tents in the thick trees. |

‘Water was dripping from the clothes hang-

ing by the Lieutenant Colonel's pup tent. |

Everybody was damp. Everybody was itch- |

ing with chigger bites. Everybody was hav- |

ing a wonderful time. |

It was just luck that we got to talking

with Blackie Jaillet instead of somebody

else. We wanted somebody who was new in

the outfit to tell us how he learned to drive

a tank. You could tell he was a selectee be-

cause he talked in the quick, nervous ac-

cents of the eastern industrial worker. Prac-

tically all the Regular Army men in the

outfit talk with southeastern drawls that you

could spread with a butter knife. The divi-

sion comes from Fort Benning,

Ga., and naturally got filled up

with local boys. Then, when

cadres were split off to form new

armored divisions, the ranks were

filled in with drafted men from

the north.

According to Blackie, it makes

a good combination. Practically

any buck private in the 2nd Arm-

ored Division will tell you he is

mighty glad he got assigned to

his company, because that is the

wildest, most reckless bunch of

tank riders in the whole lot. In

this Blackie Jaillet is no excep-

tion. He figures his outfit is

good for just about anything.

There is really nothing excep-

tional about Blackie, unless it is

his luck in getting a tank to

drive and the speed with which

things have happened to him.

He is just one of the mechanical

fingered American boys who,

during the past year, have been

tossed into the Army and told to

become tank soldiers. It seems

to have worked very much like

throwing a hatch of ducklings

into a puddle.

Leandre Joseph Jaillet, as the

baptismal records call him, is a

little fellow with dark eyes and

a quick, lopsided smile. That is,

he looks small because his mates

are so big, and the compact

build inside his coveralls doesn’t

show his 159 pounds. He came

from New Bedford, Mass., where

his father had been a deep-sea

diver. He went to high school

there three years, played foot-

ball. But last year he was work-

ing a lathe in a machine shop at

Gardner, Mass.

Blackie was 21 just in time to

be caught by the draft, and his

number came up early last Jan-

uary. Defense contracts were coming into

the shop, and he probably could have made

a good plea for deferment. But he decided

to take things as they came.

“How'd you like to go down to Benning

with the Armored Force?” the Army people

asked him when he told them he was a

mechanic.

“0. K.,” said Blackie. “I gotta spend a

year anyway.” He was philosophic about it.

So he went to Georgia and first put in six

weeks at basic training. Practiced close-

order drill, how to use a rifle, machine gun,

pistol. Though he’s been wearing coveralls

ever since, he learned how to wrap his leg-

gings. He practiced driving a truck.

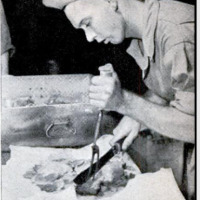

Assigned to his outfit, he spent his first

day cleaning up a tank which had been

working in the mud. That taught him

plenty about the tank, all its cracks,

crannies, and crevices.

They took him for a ride and that

got him all excited, for he rode stand-

ing in the turret, hanging on and

bumping his ribs while the tank

twisted and turned, jumped and ca-

reened, clattering and banging with a _

terrific uproar. The old-timers were

giving the kids a workout, drilling in

their unofficial motto—reckless driv-

ing preferred. That is, it must seem

like reckless driving, but a man must

know what he is doing. No yellow

drivers wanted, said the sergeant. If

you were going to jump off a bank,

you had to pancake, land bellywhop-

per, and to do that you had to be going

anyway 35 miles an hour.

Blackie was to learn that on his first

maneuver problem. The corporal driving

took the tank off a seven-foot precipice and

did it too slow. The tank nosed straight

down, and the kid in the turret was pitched

out, into the hospital for a long time. They

weren't going fast enough, says Blackie,

though he never quite figured out what

would have happened if they'd tried to pan-

cake off a bank that high. He hasn't been

back to try it.

The second day Blackie started driving.

An instructor showed him the controls, then

took him to a place where a two-acre area

had been marked off.

“This place is all yours,” he said. “Take

it away.”

So Blackie drove to his heart's content,

learned how the thing handled, practically

by himself. Steering was easy, he found out

quickly. You have a lever in each hand.

Pull back on one, and it stops the track on

that side, speeds up the other track. Work-

ing them back and forth, right and left, you

can twist and turn like a snake. :

But that wasn’t the half of it. The real

art of driving a tank is in shifting the gears.

‘To slow down or stop, you don’t step on the

brakes; you shift into a lower gear. You

have five forward speeds, and you use them

all continually. To keep from grinding the

gears, the driver must be an expert at

double-clutching—going into neutral, engag-

ing the clutch, bringing the engine speed

into time with the lower gear, then complet-

ing the shift. He's got to do it just as nat-

urally as you'd slip your car from second

into high, if he wants to do a smooth job.

Blackie got the hang of it quick-

ly. These light tanks are powered

with an airplane-type radial Diesel

engine, a nine-cylinder Guiberson,

and it is important to keep the

r.p.m. within a certain range—

1,400 to 2,200 is about the maxi-

mum spread, and 1,800 about right.

You have a gauge to tell you the

revs, but Blackie soon learned to

tell them by listening. He learned

never to let his engine labor, al-

ways to go into a gear at which she can

easily handle her 13 1/2-ton load. i

This was a lot different from car driving.

You couldn't casually step on the gas or the

brake. You couldn't lean back and let the

tank drive itself. A tank is never under

control, and you must keep driving it every

minute. Blackie learned to go into a lower

gear before he came to a ditch or a curve,

s0 that in any maneuver he could keep the |

engine and tracks pulling. Against all his |

instincts he learned that he must give her |

the gun on a curve, so as not to slacken off

on track tension and throw a track.

About this time Blackie had been in the

Army two months. His base pay continued

at $21, for four months, before it went to

$30. And now he got a rating as a mechanic,

5th class, which meant $6 extra,

Sergeant Curtis Mitchell, from Eupora,

Miss., who rides a tank like a broncho, was

putting Blackie through the jumps. Blackie

needed his big helmet, like oversized foot-

ball headgear, as the iron horse bucked and

careened,

“Monkey see, monkey do,” said the ser- |

geant. “Drive her this way. That's the way

to learn.”

You can't relax when you're driving a

tank, and there's no taking it easy in the

training for it, either.

Within a week Blackie was driving in a

convoy, straining every nerve to keep at the

proper 50 yards distance from the tank in

front of him. The sergeant taught him to |

watch for a burst of exhaust smoke from

the tank ahead. That meant the driver was

speeding up his engine in order to shift gears

and slow down. So Blackie had to shift

quick too. |

Blackie learned to drive by nose and by

ear. Moving in convoy by night, blacked

out, your little blue lights show you only

about ten feet of the road ahead. But you've

got to keep that 50-yard space, for safety

from bombing. Blackie learned quickly to

slow down when he smelled a fresh blast of

exhaust smoke from his leading tank. But

the ear business was harder. Amid all the

clatter and banging of the tank, like a mov-

ing boiler factory, he gradually learned to

pick out the humming sound of the muffler

ahead. When that humming increased it

meant to speed up, the tank ahead was go-

ing faster.

A tank outfit is no place for a tree lover.

Blackie learned to drive in the woods, mow-

ing down the pines like weeds, apparently

with reckless abandon, actually with tense

care—twisting and dodging among the trees

where feasible, or banging square into them

and pushing them over. You mustn't bang

your tracks into a tree, but pick your tree

and take it full between the tracks. A light

tank pushes over an eight-inch pine tree

easily, but a smaller oak or hickory will

give it a jot.

Blackie learned to duck around a tree

that was leaning toward him. It might fall

toward the tank, instead of away, and kill

the man in the turret. He learned to be

careful about back-tracking—that is, driv-

ing back in the opposite direction over a

woods route where tanks have come. First,

the ground may be all mushed up and bog

you down. Second, there will be a sapling

‘pushed over, which has sprung back up just

enough to crash in through the openings of

the tank like a shattering spear. Back-

tracking through the woods you always

have to button up—close up your armor

plate and drive blind.

Driving in a blackout is like blindman’s

buff, but driving buttoned up is worse. There

is only a tiny slit to see through, and the

driver can only give perfect obedience to the

man standing in the turret. Foot on the

right shoulder, turn right; foot on the left

shoulder, turn left; kicks in the back for

other things. Teamwork and implicit trust

is what this takes.

Blackie was just getting good when they

raised his pay again—to 4th Class Specialist,

$45 a month—and sent him to Fort Knox

for three months. There he studied gas en-

gines intensively, not just tank engines, but

truck and car engines—stuff that will be

useful all his life.

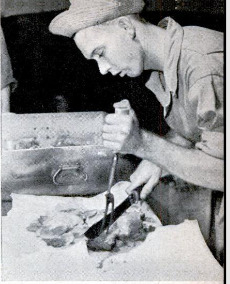

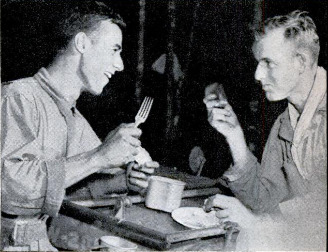

He got back to his outfit in July, feeling

pretty cocky, and was put on K.P. duty for

a week. Everybody in the 66th does his

trick at K.P. And when Blackie got another

advancement, to 3rd Class Specialist, $50 a

month, he didn't feel at all bad about it.

Soon after this Blackie got his full permit

as a tank driver. (Army drivers have per-

‘mits, like civilian licenses, qualifying them

for driving different kinds of vehicles.) And

incredibly soon thereafter, he found himself

put in complete charge of a tank. Ordinarily

a noncommissioned officer commands a tank,

but with so many being moved to other out-

fits, or going to school, nowadays frequently

a private gets the chance.

There was only one trouble. None of his

three-man crew was yet fully qualified to

drive in maneuvers, so Blackie had to do

the driving himself and put one of his men

in the turret. But that was only for a short

time. Blackie was monkey-see-monkey-do-

ing them at a great rate. Soon he would

ride in the turret of his own tank, just like

the general.

‘That's Blackie's story. Nothing especially

startling about it. But multiply it a few

thousand times, and then you have some-

thing. Blackie's glad he went in the Army.

He thinks it's treated him fine.

He's hoping he won't get that $10 raise

Congress has promised for the second year

in the service. He has a girl back home.

He calls her up every payday, but that is

not so good as being there. At the end of

his year he'd like to go home to his job.

But of course, if Uncle Sam really needs

him longer, that will be O. K. by Blackie.—

HICKMAN POWELL.

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

Eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1942-01

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

114-120

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

Popular Science Monthly, v. 140, n. 1, 1942

Popular Science Monthly, v. 140, n. 1, 1942