-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

2.500.00 worth of planes a day: he built his engineering genius into planed that are fighting our enemies on land and sea

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: 2.500.00 worth of planes a day: he built his engineering genius into planed that are fighting our enemies on land and sea

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

Donald Douglas set that as a production goal in filling orders for 654,579,973.26 that goal on schadule-just as he has always come through on every job he has ever tackled

ONE afternoon in the early summer of

1909, only six years after the

‘Wright brothers were catapulted

from Kill Devil Hill into the world’s first

heavier-than-airflight, aslender youthnamed

Donald Wills Douglas hurried over from

‘Washington to Fort Meyer, Va., to catch his

first glimpse of an airplane. For an hour, the

famous brothers tossed wisps of dust up to

test the breeze. At last they roared out over

the corral, their chattering engine and beat-

ing propeller frightening men and horses.

Chance got the wide-eyed youth his op-

portunity to be in near the birth of aviation.

He had received an appointment to the U. S.

Naval Academy, subject to a bit of surgery,

and had gone to Washington a few days

earlier to enter a hospital. A few weeks

after observing the dem-

onstration, he became a

plebe, and celebrated by

launching from a dormi-

tory window a model

plane put together by his

own hands. The plane

promptly smacked into

an admiral's cap as that

officer strolled along a

walkway outside.

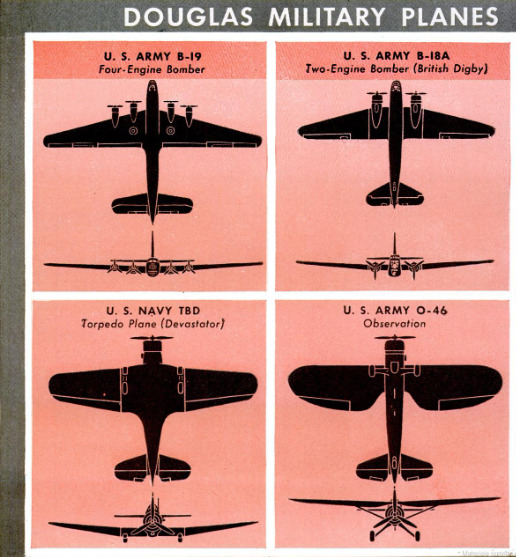

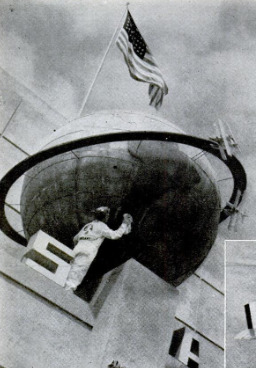

Thirty-two years later,

the same Donald Doug-

las on an early summer

afternoon walked diffi-

dently from a hangar at

Clover Field, near Santa

Monica, Calif., heard four

powerful engines ticking

methodically on the larg-

est airplane ever built.

The great bird was the

B-19, a bomber capable

of carrying a huge load

of bombs across an ocean

and returning home

again. For miles in all di-

rections, 100,000 people

jammed the highways for

a glimpse of another his-

toric flight. Shortly, the pilot gunned the

engines, and the B-19 soared into the sky.

Between Fort Meyer and Clover Field,

Donald Douglas in three decades has

achieved world eminence in aviation. From

the time he set out to build an airplane, in

1921, until today he has never experienced

failure. His passenger liners span the na-

tion on 17 airlines, serve 52 foreign coun-

tries on another 18 lines; cargo and troop

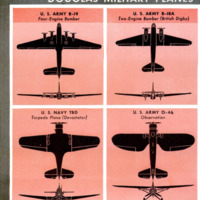

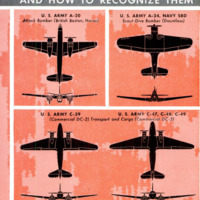

carriers, dive bombers, medium bombers, and

huge four-engine bombers from his factories

are fighting for Uncle Sam and his allies.

Every day a million dollars’ worth of new

airplanes roll from his assembly lines.

Although his designs have revolutionized

commercial aviation and added mightily to

our aerial defense, Douglas has everlastingly

avoided the spotlight. He'd rather lose a

tooth to the dentist's forceps than make a

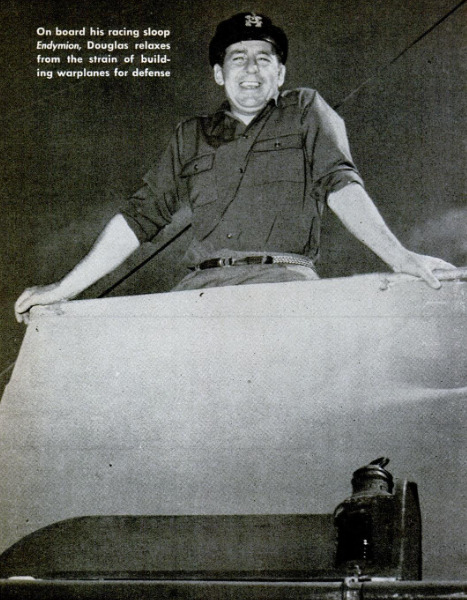

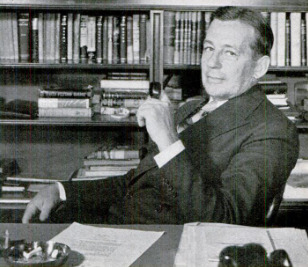

speech. Bronzed by frequent week-ends off

the California coast on his racing sloop, he

spends long days at a large desk in a small

office where he devotes his engineering and

business genius to planning new planes to

fight our enemies.

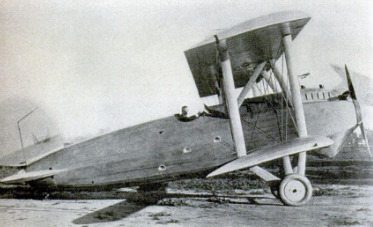

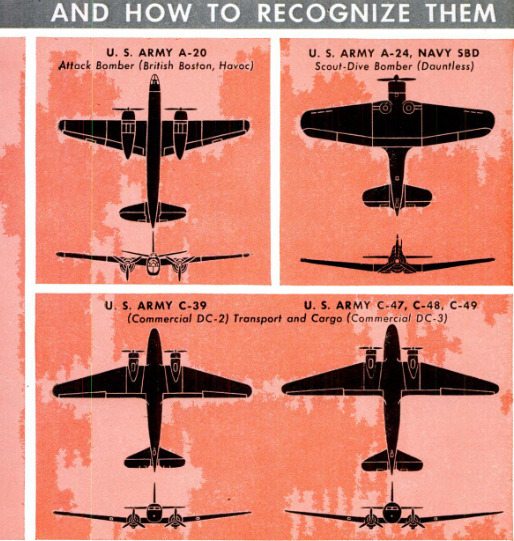

‘As an engineer, he has won the coveted

Collier and Guggenheim awards. From the

business angle, his enterprises have shown

a profit ever since he became a builder of

airplanes 20 years ago, from the two-place

Cloudster, a biplane which introduced new

techniques in streamlining, to his A-24 dive

bomber, so good that Army authorities de-

clared two squadrons “out-Stukaed the Ger-

man Stukas” in the recent large-scale war

games down in Louisiana.

Douglas is a “pilots designer.” Above and

beyond his engineering skill, however, you

find a single-mindedness rare in manufac-

turers. When he left the Naval Academy in

1912, his mind was focused on wings and

skies. That autumn he enrolled in the Mas-

sachusetts Institute of Technology, graduat-

ing two years later and receiving immediate-

ly a year's appointment as assistant in

aeronautical engineering. Salary, $500 per

annum.

Young Douglas moved rapidly during the

next few years. At M.L T. he helped build

the first wind tunnel. Next year found him

at the Connecticut Aircraft Co., building the

first dirigible constructed in the United

States, the D-1. Shortly Glenn L. Martin

brought him to his firm as chief engineer,

and young Douglas’ skill entered into the

design of the famous twin-engine Martin

bomber, a landmark in military aviation.

Now only 25, he already

had won national recog-

nition. Another jump land-

ed him in Los Angeles,

“approximately broke” but

blessed with boundless con-

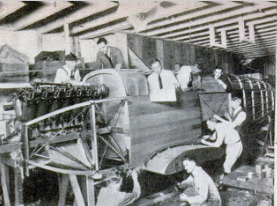

fidence in his ability. On

the West Coast Douglas

met a wealthy young man

named David R. Davis,

who owned a small ma-

chine shop and wanted to

get into aviation. Douglas

sold Davis on the idea of

building a reconnaissance-

type plane, streamlined

and equipped with instru-

ments. A few months later

the Cloudster, conceived on drawing boards

hugging the wall of a small barber shop,

was perfected.

I talked to Eric Springer, test pilot for

Douglas and Davis when the Cloudster was

born and today manager of the El Segundo

plant, building A-24’s for the Army and

their counterpart, the SBD, for the Navy

and Marine Corps.

“Doug knew where he was headed then,

and he's never given us a chance to forget.

You can think of the Cloudster, or any of

the 150-0dd models since, as a cocktail. It's

got to have the right proportion of all in-

gredients before it's served to a customer.

“Every Douglas ship,” Springer contin-

ued, “represents a compromise. Not the

fastest, maybe, nor the highest-flying, nor

will it carry the heaviest load possible. But

it'll be a pilot's airplane, combining speed,

economy, and loadability.”

Springer and Davis took off from March

Field, the Army flying base in Southern

California, early on the morning of June 25,

1921, hoping to make the first transconti-

nental nonstop flight. They reached El Paso

ahead of schedule, when one bank of the

timing gears failed just as they roared over

Fort Bliss. Springer slid down to a dead-

stick landing, and the attempt was written

off as a failure when Lieutenants Kelly and

Macready made the flight in a single-en-

gine Fokker monoplane a short time later.

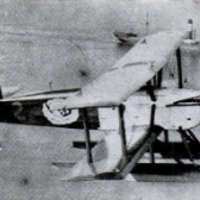

The failure was only apparent, however,

for the Navy shortly requested specifica-

tions for a torpedo plane, inviting both

American and European companies to par-

ticipate. The ship was to fly from pon-

tons, and be powered with a 400-horsepow-

er Liberty engine. From the data perfected

in building the Cloudster, Douglas turned

out the winning design, of which the Navy

bought 61 copies. This led to development of

a new series with which U. S. Army officers

in 1924 succeeded in flying 25,000 miles

around the world.

In 1932 the airlines, just crawling up from

the depression, faced the necessity of in-

creasing their speed, providing greater com-

fort for day passengers and beds for those

flying at night, and cutting operating costs.

Early in 1933, TWA officials decided speed

must be upped 50 miles an hour, that other

characteristics of safety and power must be

provided. Douglas and four other manufac-

turers received requests for bids, one re-

quirement being that the plane accepted

must be able to fly from any regular airport

in the country on one engine, proceed to the

next scheduled stop, and have a legal reserve

of gas remaining in the tanks on arrival.

TWA awarded the contract to Douglas, and

a new era in American air transport began.

Douglas built the DC-1 for peacetime fly-

ing. The ship upped cruising speed from 100

miles an hour to 150. With a few changes,

the production model became the DC-2.

Shortly, improvements were incorporated in

a third model, the DC-3. Whereas 186 DC-2's

were built, more than 1,500 DC-3’s will have

been constructed by early next year for the

air lines, and for the U. S. Army for employ-

ment as troop and military cargo carriers.

The DC-3 series gave world travelers their

first taste of real flying comfort, and as they

drew increasing numbers of passengers into

the air, brought the lines out of the red. To-

day these 25,200-pound planes, after five

years without a major structural change,

are still standard equipment.

Sitting at the hub of a large engineering

and manufacturing organization, Douglas

can’t poke his finger into every detail, but

he guides the preliminary design of any new

ship, whether transport or bomber. He leaves

details to his experts.

Seated in the quiet of his paneled office,

we might have been a thousand miles from

the clatter of riveting and roaring of test

engines just beyond the soundproof walls

when I asked him to look into the future.

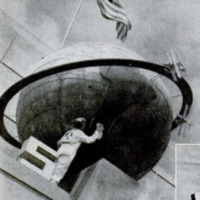

“Let's start with invisible bombing,” I

said. “How high will the bombers fly?”

“Some of our plans must remain military

secrets,” he warned, “but I can go this far:

Recently we have completed a ‘cold room,”

where the thermometer drops down to about

105 degrees below zero. In that room we're

testing oxygen apparatus, paints which we

hope will not chip and flake in extreme cold,

metals, and men.” The “cold room,” whose

temperatures fall below those flyers experi-

ence at the highest levels any plane today

can reach, is the laboratory where he’s get-

ting ready for stratdspheric bombing.

Douglas considers the fabulous B-19 to

be the guidepost which may usher in an era |

of superbombers of which no more than a

half dozen fighting airmen dared dream as

recently as a year ago.

“Suppose,” he said, “we're asked to jump

from our 30-ton bombers to a machine of |

200,000 pounds. The big fellow might fail

unless we know where we're heading. The

B-19 gives us fine supporting evidence on

which to build a 100-ton bomber. She is a

point from which we may embark on designs

for planes capable of carrying much heavier |

bomb loads out of sight in the stratosphere

for long distances.” |

But Douglas also has his eyes fixed on the

needs of peace. He sees, first, shipyards

taxed to capacity turning out freighters.

For several years, in his opinion, few pas-

senger liners will be built. This leaves an

opportunity for a tremendous aviation con-

struction program.

“Low fares,” he suggested, “should open

up tremendous ocean trade for both pas-

sengers and freight. Trans-oceanic flying is

receiving its impetus now, and the long-

range bombers will furnish the designs

from which we may turn our assembly lines

to long-range seagoing land planes.”

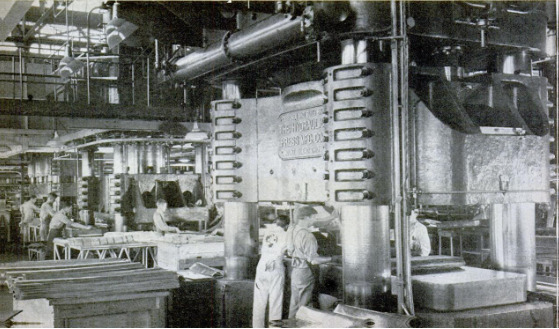

Engineer, salesman, executive, financier—

Douglas is all these. But first he is a builder.

From his El Segundo assembly line attack

bombers, A-24 and SBD, move on to the

Army and Navy. The Santa Monica factory

assembles DB-7 Havocs for the British and

A-20’s for Uncle Sam (similar to but better

than Havocs), plus Army troop-cargo car-

riers. The new blackout plant at Long

Beach turns out more troop-cargo ships, and

mighty B-17E bombers developed by Boeing

for the Army Air Corps.

Soon after the newest plant at Tulsa, Okla.,

was dedicated in October, Consolidated B-24

bombers, fabricated and subassembled by

the Ford Motor Company, were taking wing.

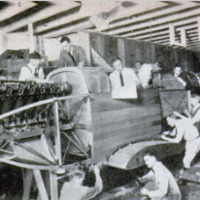

Today Douglas employs 32,000 men and

women. By June there will be 75,000 persons

on his payroll, working in plants spread

over 5,000,000 square feet. As I write, armies

and navies, with such civilian customers as

priorities permit, have swamped him with

a backlog of $654,579,973.26, enough to keep

him going at top speed for many months.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Andrew R. Boone (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

Eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1942-03

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

52-58

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

Popular Science Monthly, v. 140, n. 3, 1942

Popular Science Monthly, v. 140, n. 3, 1942