-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Before the bomber observations: hot ships take over as eyes of the army

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: Before the bomber observations: hot ships take over as eyes of the army

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

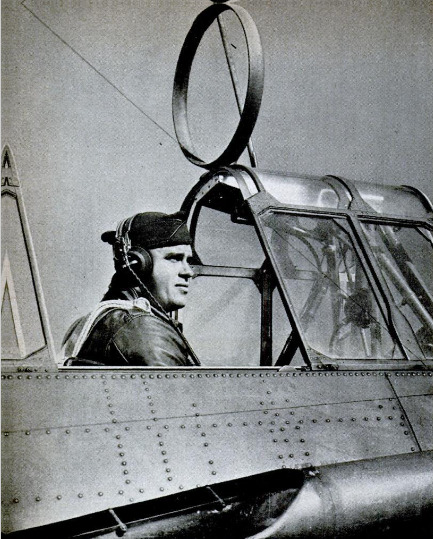

WHEN young Howard

P. Olsen joined up

with the Army as an air

observer, he had no idea

he would soon be up to his

ears in some of the fastest,

most exciting, rapidly

changing doings in mili-

tary science. But as mat-

ters are moving now, he

may even turn out to be a

romantic figure. That would surprise no-

body more than Howie. He wasn’t looking

for glory when he joined the 126th Observa-

tion Squadron.

Observation outfits had been the chore

boys of the air force. The observer's work

was of the utmost importance. It called for

intense specialization, technical knowledge,

and mathematical precision. But it hadn't a

bit of glamor about it. An observer was

the Army flyer who was not part of the

swashbuckling GHQ striking power. An ob-

server could never be an ace. Once in battle

he would take plenty of risk, get none of

the credit, and never be in on the kill.

Meanwhile he floated around in a bum-

bling old-lady type of plane with a goldfish-

bowl canopy, a popgun armament, and a top

speed of 175 miles an hour, telling the field

artillery whether it was on or off the target.

With present-day speeds of fighter planes, a

fellow, might as well be flying a captive

balloon, for all the security it gave him.

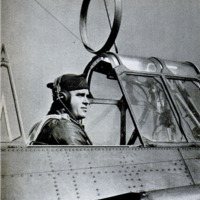

But that ended with the first bomb on

Pearl Harbor. Today no plane is too hot for

an observer. And when faster planes are

built, observers will fly them too. American

observers have been getting their new

methods ready ever since they were de-

veloped out of British experience. All they

needed was a little more training with their

new ships to be ready to fly right into the

jaws of the enemy to get the vital informa-

tion without which there can be no victory.

This article about new observation meth-

ods begins with Howie Olsen, not through

any intention to glorify him above any of

the hundreds of other fine young fellows

who will be doing a similar job, but because

it’s a good idea to get these things down to

human terms. War communiqués are cold-

blooded things, but they cover the exploits

of hot-blooded young men.

‘When you hear that a fleet of American

‘bombers has blasted the living daylights out

of the Japs or Nazis at some far-distant

point, just remember that some fellow like

Howie was there first— perhaps several

times—to pick out the objective, to make

photographs which would show the value of

attacking it.

Maybe he flew in the nose of a light twin-

engined bomber, with a pilot and two gun-

ners behind. Quite likely he flew over enemy

territory all by himself, with only his own

speed and marksmanship to protect him—

in a P-38 pursuit ship high in the substrato-

sphere, diving down below the clouds,

running off a series of photographs, and

zooming upward again to high-tail for home.

Going into the Army was about the last

thing Howie Olsen wanted to do back in

1940. He had finished the course in com-

merce at the University of Wisconsin in

1939 and was an up-and-at-'em young busi-

ness man of Madison. He had worked his

way through college running a filling sta-

tion; now he had two filling stations and

also a good job with a firm of public ac-

countants, traveling around the Middle West

auditing the books of business corporations.

He wasn't interested in the military life,

but when he felt his number coming up, late

in 1940, he began to look around for a spot.

About this time Maj. Paul D. Meyers was

called back from New York to Wisconsin by

Governor Heil to organize an air-observation

squadron for the Wisconsin National Guard.

Paulie Meyers was a Wisconsin football hero

back in the days before and after the last

war. Howie had been a football and basket.

ball man at Madison too, and Meyers asked

him to join up. Howie jumped at the chance. |

So did a lot of other fellows. Paulie Meyers

‘was able to pick his 115 enlisted men from

1,500 applicants who were eager to serve

under him. The 126th Squadron was green

When called to active duty at Fort Dix, N.J,,

last June, but it had all the makings of a

crack outfit. |

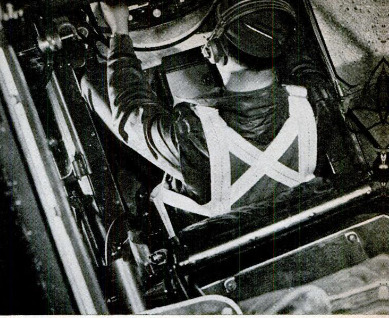

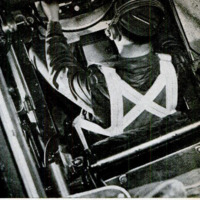

As a newly commissioned observer lieu-

tenant—not a pilot—Olsen soon found that

he had an intensive course of studies cut out

for him. To be an efficient observer, he had

to know photography; he had to be able to

handle radio, either key or voice, (There's

a lot of technique in talking through a little

voice radio, and making yourself under-

stood.) He had to master navigation, to |

Jnow exactly where he saw activity or took

a photograph. He had to study meteorology

and practice gunnery. On a military mis-

sion, the observer would be in charge of

everything except the actual piloting of the

plane, and he had to know his job from the

roots up. |

Above all, he had to understand what he

was seeing when he looked down from a |

plane on the crazy-quilt landscape moving

below, not only to recognize it but also to |

understand it in terms of military tactics

and strategy. He must know the signifi-

cance of what he saw, and what to report

back by radio to his base. That was new to |

Olsen, but as to understanding the landscape

he had a head start. He had flown planes |

himself for 350 hours while he was in col- |

lege. His roommate had been manager of

the local airport, and Howie had made the

most of it.

It was only because he didn’t yearn to

spend years in the Army that he hadn't gone

out for training as a flying cadet. But now,

as he began to learn the significance of the

new developments in observation, he began

to reconsider. When I last saw him, just

before the declaration of war, he was plan-

ning to put in for Kelly Field, so that he

could combine his training as observer and

pilot. It seems quite likely that he will be-

come an observer-pilot. Certainly we are

going to need plenty of them.

Observation ideas were knocked galley-

west in the first days of active fighting in

Europe. Britain, like the United States, had

developed a special type of slow, easygoing

plane for observation, built to give plenty of

opportunity to look around. Thought was

dominated by the World War concept of a

stabilized front, with planes used to observe

the effectiveness of artillery fire and events

close to the battle line. But promptly the

British found that in a quiet sector of fight-

ing, their mortality among observers ran

at the rate of 60 percent a week. They had

to recruit and train a whole new crop of

observers, and put them in a new type of

ship. That ship was a Spitfire, stripped

down so it could carry plenty of fuel, and

equipped with a fixed, automatic camera.

The camera could see and retain far more

informing facts than could a speeding flyer.

And back at the bases, ingenious new meth-

ods were developed to interpret the pictures.

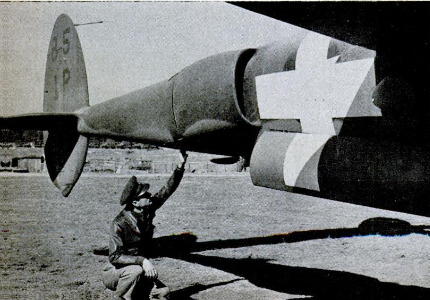

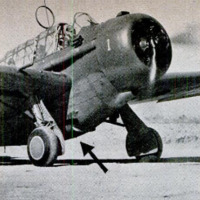

The plane used for training by the 126th

Squadron was of the old observation type,

the 0-47, a fine, well-mannered ship carry-

ing three men—pilot, observer, and a rear

gunner with a .30 caliber machine gun on a

revolving mount. It was a fine training ship

from which to make photographs, look for

armored columns and supply trains on dusty

roads, report back by radio.

One day when I was with the 126th during

the Carolina maneuvers, one of Olsen's col-

leagues, Lieutenant Jefferson, discovered

an “enemy” airport loaded up with transport

planes warming up for a take-off with air-

borne infantry. He made photographs, tried

desperately to get a response from his home-

base radio as he broadcast the news. Then a

trio of Red army pursuits dived at him, and

he was “shot down.” He came back to his

base with his theoretically nonexistent pic-

ture, thinking his mission had failed. But

then he heard that his message had got

through. Blue bombers had dashed in and

“annihilated” the enemy force.

The significant thing about this little in-

cident was that Jefferson was “shot down.”

In just a few days of operations in a quiet

part of the Carolina front, with only one

plane going on a mission at a time, practi-

cally the whole flying personnel was “shot

down” at least once. That would probably

be 100-percent mortality per week. but of

course no such thing will be per-

mitted.

All idea of using the O-47’s in

actual battle, of course, had long

been discarded. The 126th was

expecting soon to be equipped

with A-20's. The A-20A is a light

bomber, otherwise known as the DB-7, the |

same plane which the British equip with

heavy guns and transform into a night |

fighter called the Havoc. The Havoc has shot

down more Nazi bombers at night than any |

other plane, and has been more effectively

used by the British than any other Ameri- |

can ship. That was good enough reason why |

the 126th did not yet have them.

The A-20A’s from the light bombardment

squadrons were used for observation mis-

sions during maneuvers, however. They

made dozens of such flights sneaking along

close to the ground at high speed until ready

to soar up and take a look, and not one of

them was “shot down.” With this ship for |

visual work, and adapted pursuit ships—the

P-40, the P-38, and the P-43—for photo-

graphic planes, American observers are go-

ing to be well equipped.

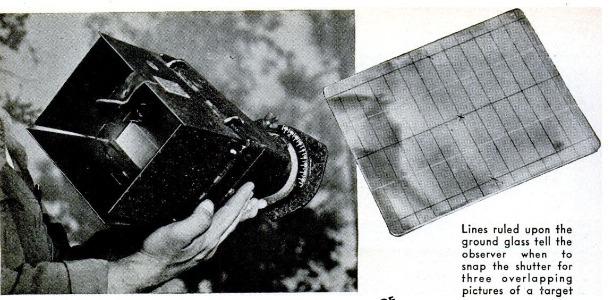

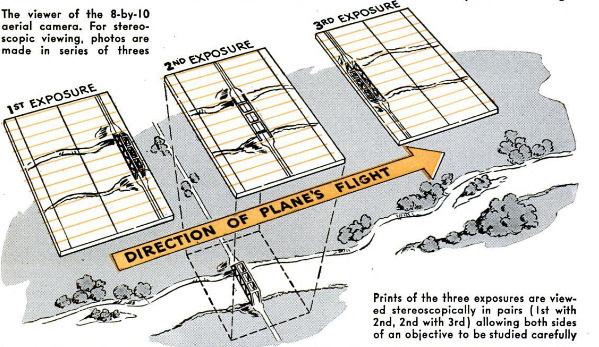

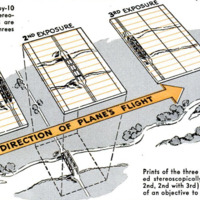

The increased speed of the observer in-

creases the importance of photography, and

newly developed use of the old principle of

the stereoscope has multiplied it. In its

photographic work the 126th was learning to

make pictures in sets of three, overlapping

60 percent. Doing that properly is a matter

of figuring out the relationship between

speed and altitude, together with the speed

of the motor which rolls the 8-by-10 film in |

the camera. But the pursuit ships being

fitted for this kind of work, and soon to be

in action, are equipped with a fully auto-

matic 5-by-5 camera, carrying 120 expo-

sures, with an intervalometer which can be

set to take the triple sets automatically.

This camera is being set in some planes ver-

tically, and in some at an angle of 45 de-

grees. By banking the plane with the

vertical camera an oblique shot can be made,

such as is often desired for the perspective

it gives. Similarly the plane with the oblique

camera can make vertical shots as it banks

down suddenly out of the clouds. The Brit-

ish use this type in the Spitfire.

The 126th Squadron’s mobile trailer dark-

room can finish (Continued on page 220)

up a set of these pictures into glossy prints

in 55 minutes after the observer hits the

ground, and then the pictures are sped off

for one of the most interesting processes

in the modern Army.

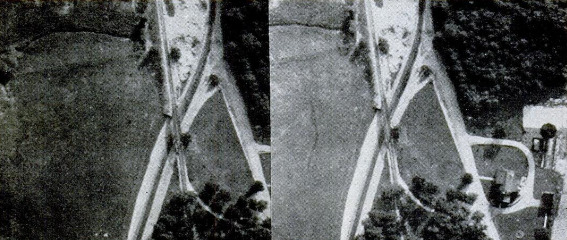

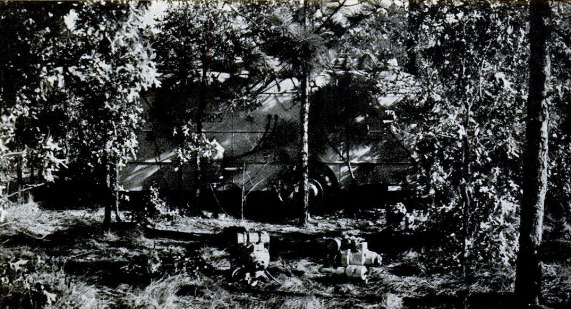

Interpretation of air photographs is an art

which has been developed intensively since

the first World War. It involves mainly the

understanding of shadows as they appear in

the pictures. Different objects cast different

types of shadows, and also in the art of

camouflage you can't paint a shadow to look

plausible at every time of day. By compar-

ing photographs made on successive days, the

interpreters often are able to detect signs

of important activity which would seem to

have been well concealed. A grove of trees

may be set up to look most convincing, but

if it grew there since last week, it obviously

is a phony.

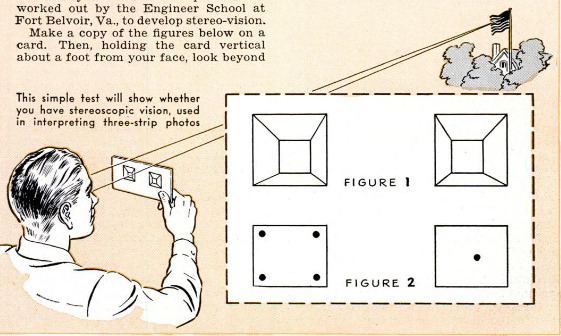

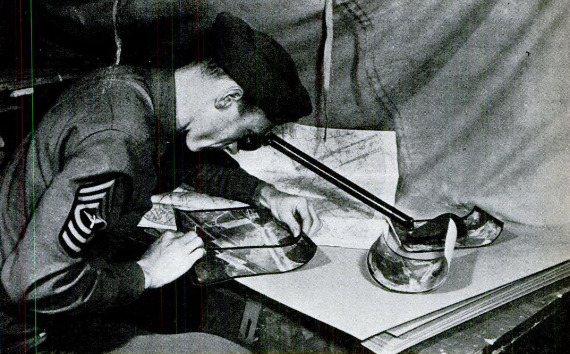

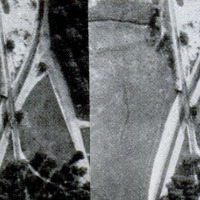

It has been only recently that extensive

use has been made of the stereoscopic prin-

ciple, on which the effectiveness of human

vision is based. A man's two eyes see two

different pictures from two points of view,

and it is through the blending of these two

in the brain that we are able to perceive

depth and judge distance. The same effect

is obtained in photography by taking two

pictures from different points of view, and

viewing them through a stereoscope.

The 60-percent overlap in aerial photog-

raphy of course exaggerates the difference

in point of view, and exaggerates the stereo-

scopic effect. The set of three pictures

enables the interpreter to look at the same

objective stereoscopically from two direc-

tions. Looked at through a stereoscope, ob-

jects in sight seem to leap from the surface

of the ground.

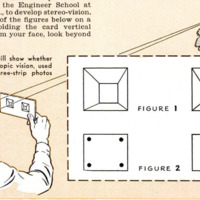

But the Army engineers, who have been

instructing large classes of officers in air

interpretation at Fort Belvoir, Md., are not

content to let their pupils use stereoscopes

to help them at the job. These interpreters

have to learn so to control their eye muscles

that they can look at a different picture with

each eye, and make them blend into a

stereoscopic image. If you see an Army of-

ficer appearing wall-eyed, with a distant

look, he probably has been practicing stereo-

scopic vision. With a little practice, one can

become remarkably skillful at this. And in

wartime speed is an important factor.

At least that's one thing Howie Olsen

won't have to learn. They don't ask ob-

servers to cultivate the glassy stare.

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

Eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1942-03

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

82-89,220

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

Popular Science Monthly, v. 140, n. 3, 1942

Popular Science Monthly, v. 140, n. 3, 1942

Screenshot_1.png

Screenshot_1.png Screenshot_2.png

Screenshot_2.png Screenshot_3.png

Screenshot_3.png Screenshot_4.png

Screenshot_4.png Screenshot_5.png

Screenshot_5.png Screenshot_6.png

Screenshot_6.png Screenshot_7.png

Screenshot_7.png Screenshot_8.png

Screenshot_8.png Screenshot_9.png

Screenshot_9.png Screenshot_10.png

Screenshot_10.png Screenshot_11.png

Screenshot_11.png Screenshot_12.png

Screenshot_12.png Screenshot_13.png

Screenshot_13.png Screenshot_14.png

Screenshot_14.png Screenshot_15.png

Screenshot_15.png Screenshot_16.png

Screenshot_16.png Screenshot_17.png

Screenshot_17.png Screenshot_18.png

Screenshot_18.png Screenshot_19.png

Screenshot_19.png Screenshot_20.png

Screenshot_20.png Screenshot_21.png

Screenshot_21.png Screenshot_22.png

Screenshot_22.png