-

Titolo

-

Short order airports

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: Short order airports

-

extracted text

-

Lightweight steel strips and chicken wire from temporary fields for fighter planes

THE FIRST military objective

in today’s type of battle is to

establish local air superior-

ity by obtaining aviation fields

close to the actual scene of com-

bat and by destroying the enemy

flying fields in that area. Engi-

neers of the Army Air Corps have

made a tremendous stride toward

this end with the development of

a portable steel landing mat which

can be installed as a usable mili-

tary airport in less than two days,

and repaired within a few min-

utes after bombing.

The steel landing field, installed

and tested at Marston, N. C., dur-

ing recent Army maneuvers, was

called “the year's greatest

achievement in aviation” by Maj.

Gen. Henry H. Arnold, head of the

Air Corps.

So simple is its construction

that it can be easily mass pro-

duced; so simple its transporta-

tion and installation that any strip of fairly

level ground, such as a South Pacific beach

front, can be turned into a hard-surfaced

airdrome almost overnight.

This may mean that the American Fleet,

advancing against the Japanese, will not

have to depend entirely on carrier-borne air-

craft. Certainly it means that an American

army moving forward in such terrain, for

instance, as the Libyan desert, can rapidly

lay landing fields as it goes, like stepping-

stones. The mat weighs only about 1,000

tons. It is transported in small units, such

as might easily be lightered ashore for a

landing from a supply ship accompanying

an expeditionary force.

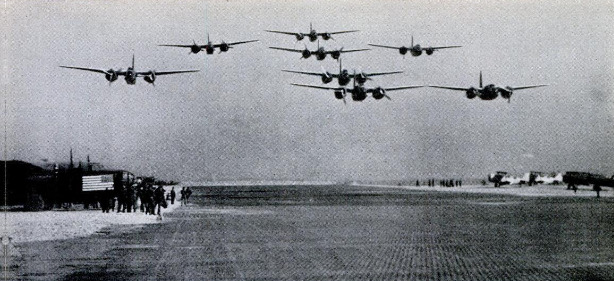

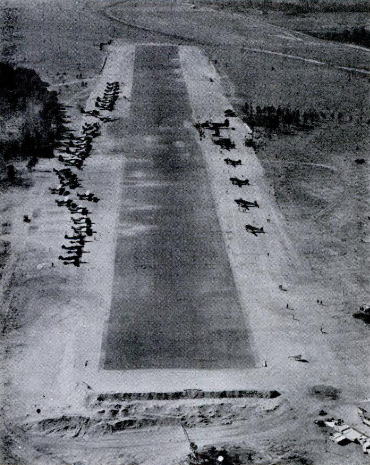

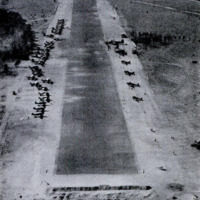

Marston Strip, as the North Carolina in-

stallation was called, was a level steel sur-

face 3,000 feet long and 150 feet wide. It

was used by all types of military planes,

from the hottest pursuit ships up to the

four-engined B-24 bomber.

Its installation by the

2nd Battalion, 21st Engi-

neers (Aviation) required

11 days, but most of this

was consumed in grading

the strip to a width of 350

feet. Actual laying of the

steel mat took only 60

hours, with three compa-

nies of 150 men each work-

ing around the clock in

eight-hour shifts. On a

beach job, with little grad-

ing required, it would be

quite possible to lay a

2,000-foot strip, 100 feet

wide, from which fighter

planes could commence operations, in a good

deal less than 24 hours.

Military planes need a long runway, but

they can use a narrow strip, which does not

have to run into the wind. With their high

landing speed, they can take off and land in

transverse winds which would ground planes

of lower wing loading. Since there is no need

to wait for concrete to dry, the portable

strip can be used by fighter planes even be-

fore it is completely laid.

A vast amount of calculation and experi-

ment doubtless went into the de-

signing of this mat, but the end

result is of exquisite simplicity.

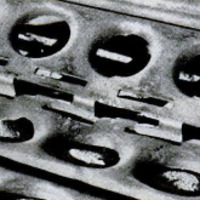

The unit is a panel of light-gauge

sheet steel. For lightness and

braking friction each panel is

perforated. Hooked together, the

joints are loose and flexible; but

When properly engaged and laid

out flat, the plates are wedged

apart into a tight rigidity.

In the design of this basic

unit, as in all other details, the

portable landing field aims at

simplicity and adaptability to a

wide range of conditions. It can

be transported easily either by

water or by land, and its instai-

lation requires a minimum of

skilled labor and heavy equip-

ment that might not always

be available at the scene -of

operations.

Vertical flanges not only con-

tribute to the weight-resist-

ing strength of the plates, but

also bite into the ground and

keep the mat from slipping un-

der the strain of braking wheels.

In case of a bomb hit, it is possible to fill

the crater with dirt and replace the de-

stroyed plates within a few minutes.

The 2nd Battalion, under Maj. Carron M.

Borror, developed a high degree of team-

work in laying the mat. This work started

at the center of the field, while grading ma-

chinery was still working toward the ends.

Once two rows of plates had been laid across

the field, at right angles to the line of traffic,

it was possible for each company to work

in two gangs of 75 men each, working out

from the center. Each gang was divided

into three crews: one to truck the plates

from the 18 flat cars which had brought

them to Marston and slip them off on the

field at regular intervals; another to en-

gage the plates and lay them; another fol-

lowing up to pound in the clips.

One gang of 75 attained a top speed of

four rows across the field—that is, five linear

feet—in five minutes.

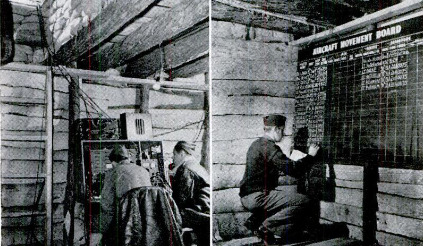

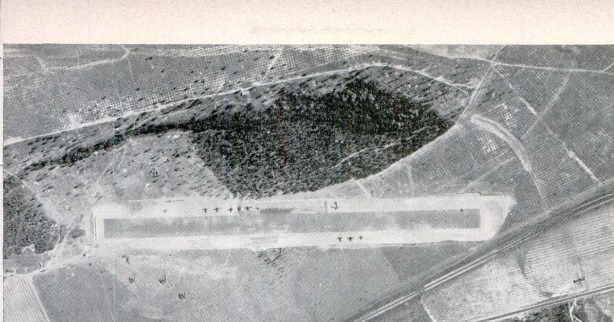

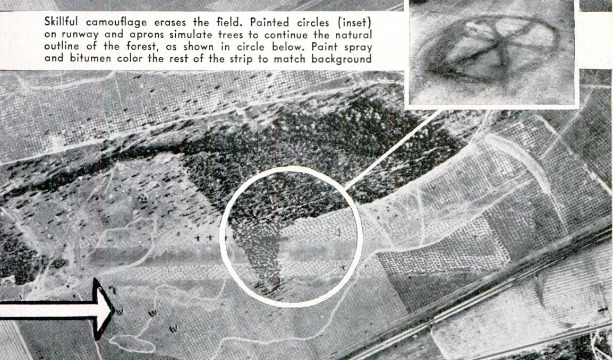

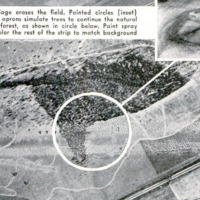

Once the strip had been laid, most of the |

engineers departed on other missions, while

Company D remained, under Capt. H. G.

‘Woodbury, to continue development of cam- |

ouflage and sandbag revetments for the

storage and servicing of planes, and experi-

ments with soil stabilization on the aprons

along the sides of the field.

Along each side of the strip was 100 feet

of newly graded sandy soil, which swirled

into vast clouds of dust from the prop wash

of planes warming up. Various methods of

tying down and hardening this soil were

tried, each of which might be adapted to

operations in a different locality. One sec-

tion was surfaced with a mixture of clay

and gravel, just enough clay to bind the soil

without getting soupy when wet. Next to

this soil cement was used. This binder,

which may also be used to make emergency

landing fields, is made by sprinkling cement

on the surface, mixing it into the soil with

a disk harrow, then packing and wetting.

This is especially useful with sandy soil. In

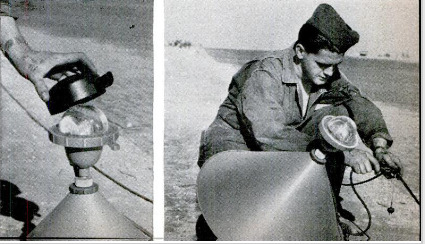

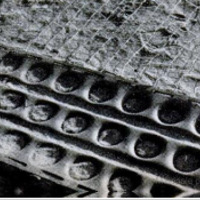

front of two revetments where airplanes

were rolled in for service, the soft sand was

held by a method developed by the British in

Egypt. Here the sand was simply covered

by strips of ordinary chicken wire, woven

together and tied down by single strands of

-

Lingua

-

Eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1042-03

-

pagine

-

101-105

-

Diritti

-

Public domain

-

Archived by

-

Sami Akbiyik