-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Dynamiters to the attack

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: Dynamiters to the attack

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

WHEN the tales of this war come to be

a the man with a satchel full of

TNT will rank with the most dashing and

intrepid of all its heroes. Whether he be

parachutist, commando, or assault pioneer

from the Corps of Engineers, he will be

operating as a lone wolf or with a small

squad of teammates; but there will be con-

centrated in him a tremendous share of the

responsibility for success against the enemy.

“Demolition” is what the Army engineers

call the old art of the dynamiter—the use

of high explosives not in bombardment or

artillery fire, but in charges placed by hand,

right where they will do the most damage.

One man with a few half-pound blocks of

TNT (looking much like a bundle of over-

size Eskimo pies) can raise more havoc, if

he reaches the right spot, than a load of

big bombs dropped in the vicinity.

‘The elements of demolition are part of the

basic training of military engineers, and the

subject covers the whole field of laying land

mines, blowing craters to impede tanks, the

wrecking of bridges, docks, and factories,

and the reduction of fortified positions by

direct personal assault.

Up to now, fighting a defensive war, we

have had demolition much in mind as part

of the scorched-earth tactics of armies in

retreat. The competent destruc-

tion of the oil wells and refineries

of Tarakan and Balik-Papan, and

the failure of such destruction at

the bases of Penang and Singa-

pore, will have deep and long-

range effects on our fight in the

Pacific. The progress of enemy

tanks has often been held up by

the blowing of wide, deep, steep-

sided craters in the narrow road-

ways of hill country.

But demolition is an even

greater offensive weapon. When

parachute troops drop behind the

enemy lines, their mission may be

to capture an airport. But they may be used just

as well for breaking up enemy communications,

wrecking bridges and railroads, preventing the ad-

vance of reinforcements. Such also is the work of

the black-uniformed, cork-faced British commandos

‘who slip ashore on the coast of oc-

cupied France to blow up ammuni-

tion dumps and otherwise harry

the Nazis and obstruct their operations.

The apparent miracle of the German ad-

vance in 1940 against supposedly impregna-

ble fortifications was largely the work of

men with bundles of explosive, who stormed

the pillboxes to lay their charges. They

were organized in combat teams of squads

and platoons, each rehearsed for a specific

task. Practically every pillbox has its blind

side, supposedly protected by guns of an-

other pillbox. While the protectors were

screened by smoke bombs, the demolition

man would slip up to the pillbox on its blind

side and place his explosive. Often this sort

of job is done with a satchel charge, a

bundle of explosive suspended from a string,

hung on the end of a stick. With this simple

equipment the attacker could whip his ex-

plosive around the side, or over the top of

the pillbox, and set it off at the most vulner-

able spot while remaining protected.

‘The war of movement has opened the field

for the guerilla, commando type of tactics.

Tanks on the march may be well-nigh irre-

sistible, but in bivouac they are vulnerable to

bush-fighters who creep

up and attack with bombs

in the dark. What the

American Army is developing in the way of

assault troops and assault tactics is some-

thing the enemy may be expected to find

out for himself, preferably by surprise.

But when the time for the attack comes,

don’t forget the boys with the satchels.

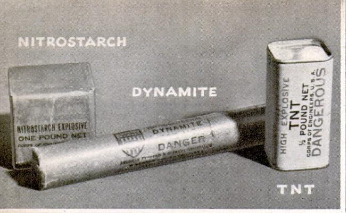

Down at Fort Belvoir, Va., little more

than a stone’s throw from Mount Vernon,

are the Engineer School and Replacement

Center, where thousands of new soldiers

are learning the art of dynamiting. In their

training they actually use dynamite, and

also nitrostarch, so as to save the more

scarce TNT for actual warfare.

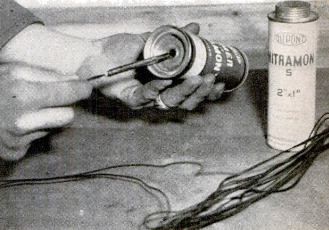

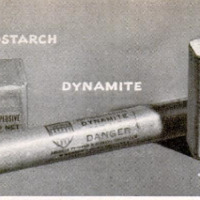

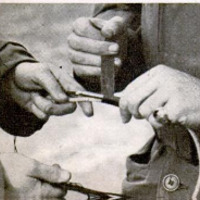

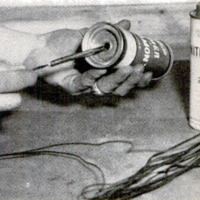

TNT (trinitrotoluene) is the standard

explosive for the U. S. Army in the field. It

is a light-yellow crystal, one ingredient

of which is toluene, a liquid now made as

a by-product in the refining of kerosene,

though some comes from the manufacture

of illuminating gas. It is put up in half-

pound blocks, 1 3/4 inches square by 3 1/4

inches long, in cardboard cartons with tin

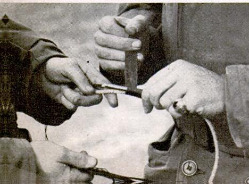

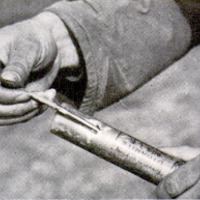

ends. There is a hole in the end of the

block for introduction of the cap. If the

hole is not large enough for the detonating

agent at hand, the explosive man has a drill

like an auger to dig out a larger hole.

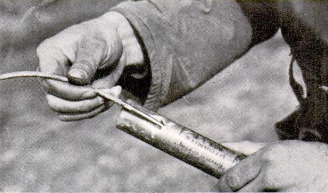

One of TNT's great values is that it is

insensitive. It can be kicked around roughly

without detonating, and small quantities of

it can be burned without explosion. A high-

explosive detonator is needed to set it off.

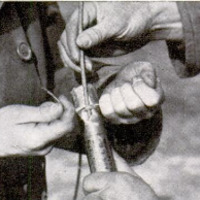

This is usually a cap made of tetryl, and

the tetryl in turn is exploded by a small

quantity of fulminate of mercury mixed

with potassium chlorate. This mixture is

very sensitive and can be set off either by

electricity or by a burning fuse.

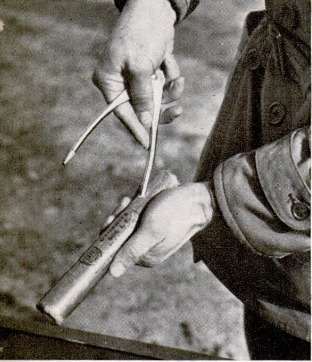

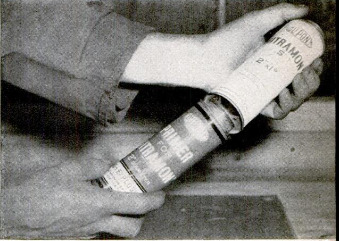

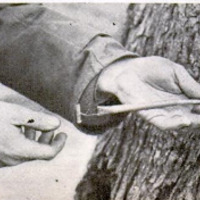

Ordinarily charges are set off by elec-

trical wiring and a small magneto known as

a blasting machine. But for quick jobs,

especially when it is desired to set off a

number of charges simultaneously, the Army

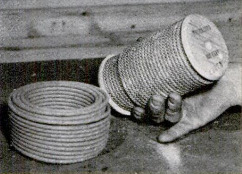

uses detonating cord, commercially known

as primacord. This is a flexible, waterproof

fabric tube, about 1/5 inch in diameter

(yellow with a rough surface for easy

identification) which is filled with a high-

explosive core—a white crystalline sub-

stance known as pentaerythritetetranitrate.

An explosion travels along this cord at the

rate of 19,700 feet a second, and it is a vio-

lent explosion sufficient to set off any TNT

in contact with it. It is especially useful in

obtaining the simultaneous explosion of a

whole mine field.

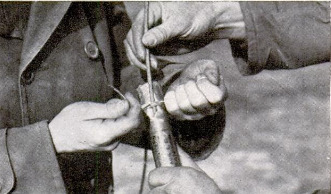

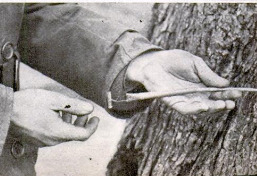

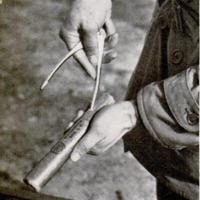

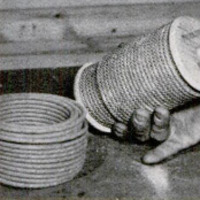

The detonating cord is also useful in mak-

ing the implement of assault known as a

bangalore torpedo, developed in the first

‘World War for cutting barbed wire. Blocks

of TNT with holes bored in them are strung

on the detonating cord like a necklace

20 feet long. This in turn is inserted in

a long iron pipe.

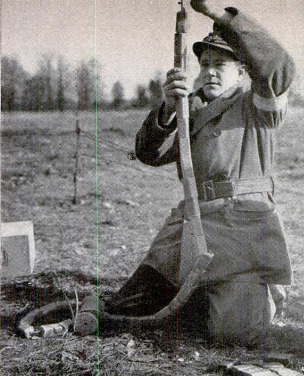

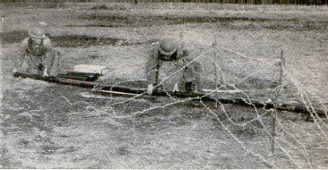

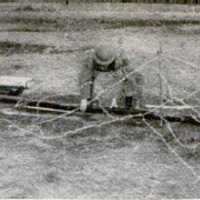

The bangalore torpedo is used to

open up a gap in a barbed-wire entan-

glement so that troops may rush

through. It is slipped under the wire,

close to the pickets to which the wire is

attached, and exploded by a fuse which

gives the dynamiter a chance to get

away to a shell hole or other shelter.

In exploding, the fragments of pipe cut

the wire like knives, and sweep the

barbed-wire entanglement clean for 20

feet or more.

All kinds of mining comes into the

work of the engineers, but this war has

developed a new kind—the trap mine, |

or booby trap. The Axis started it,

leaving all sorts of fiendish practical

jokes behind them in territory from

Which they have retired. If you found |

a bright new fountain pen lying on the

Libyan Desert, you wouldn't dare to |

pick it up. It probably would be at-

tached to the trigger of a mine, which |

would blow you to bits.

The effectiveness of booby-trap mines |

against an army of occupation lies in

their not conforming to any pattern.

In their training lesson on booby traps,

the soldiers have issued to them a mot-

ley collection of ordinary mouse traps,

spring clothespins, flashlight batteries, |

nails, and rubber bands, together with a |

supply of low-power caps to set off fire-

crackers. From then on it is up to them

to improvise strange Rube Goldberg in- |

ventions to entrap the enemy.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Hickman Powell (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

Eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1942-06

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

44-49

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

Popular Science Monthly, v. 140, n. 6, 1942

Popular Science Monthly, v. 140, n. 6, 1942

Screenshot_1.png

Screenshot_1.png Screenshot_2.png

Screenshot_2.png Screenshot_3.png

Screenshot_3.png Screenshot_4.png

Screenshot_4.png Screenshot_5.png

Screenshot_5.png Screenshot_6.png

Screenshot_6.png Screenshot_7.png

Screenshot_7.png Screenshot_8.png

Screenshot_8.png Screenshot_9.png

Screenshot_9.png Screenshot_10.png

Screenshot_10.png Screenshot_11.png

Screenshot_11.png Screenshot_12.png

Screenshot_12.png Screenshot_13.png

Screenshot_13.png Screenshot_14.png

Screenshot_14.png Screenshot_15.png

Screenshot_15.png Screenshot_16.png

Screenshot_16.png Screenshot_17.png

Screenshot_17.png Screenshot_18.png

Screenshot_18.png Screenshot_19.png

Screenshot_19.png Screenshot_20.png

Screenshot_20.png Screenshot_21.png

Screenshot_21.png Screenshot_22.png

Screenshot_22.png Screenshot_23.png

Screenshot_23.png Screenshot_24.png

Screenshot_24.png