-

Titolo

-

Gas attacks from the air

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: Gas attacks from the air

-

extracted text

-

WHEN the almost incredible striking

power of air chemical warfare is re-

vealed, the world will be as sur-

prised as it was by the success of the first

German mass attacks by tanks and mech-

anized troops supported by airplanes. Chem-

icals could be used from the air on a

tremendous scale—not by single flights or

squadrons of aircraft, but by massed squad-

rons of planes dropping gas in overwhelm-

ing quantities.

There is no doubt that the airplane pro-

vides the best method of disseminating cer-

tain types of gases, and I am confident that

large-scale dispersion of mustard, or the

other powerful blister gas, lewisite, would

cause a complete revision of our present

ideas of how to wage war. Despite treaties

and international agreements, no nation has

abandoned the chemical weapon.

The problem of protection against gas is

tremendously complicated by the airplane,

and the country must recognize and prepare

for the added burdens which air chemical

warfare might put upon it. During the first

World War chemicals were not used from

the air; gas was dispersed entirely by

ground weapons, and never penetrated more

than ten or 12 miles behind the front lines.

Today the wide radius of action of aircraft

and the development of effective means of

projecting gas from airplanes radically

change the entire aspect of chemical warfare.

‘There will no longer be any areas in which

anti-gas measures are unnecessary; any-

where that a bomber can reach there may

be danger of gas. Industrial and transpor-

tation centers far behind the actual combat

zones, as well as communication lines, troop

concentrations, food and ammunition dumps,

and all military installations, may be sub-

ject to attack; and at all points within range

of enemy aircratt protective equipment will

be maintained ready for instant use.

When the words “chemical warfare” are

mentioned, most people immediately think,

“poison gas.” Although this term is widely

used, it is really a misnomer, for most of

the chemical combat substances are liquids

and solids. They are roughly classified by

American military authorities as “persist-

ent” and “nonpersistent.” If no protection is

needed after ten minutes, as is generally the

case with phosgene, chlorine, and other

highly volatile gases which vaporize entirely

at the moment of release, they are non-

persistent. If the amount effective after ten

minutes is enough to make a man put on his

gas mask, the substance is said to be per-

sistent.

Some of the liquids which will be used in

future air chemical warfare are remarkably

persistent. Mustard gas,

still regarded as probably

the most effective casualty-

producing gas yet developed,

remains effective on the

ground in the summer from

a day to a week or more,

and in cold weather it may

persist for several weeks.

Throughout that time it is

a constant danger.

Persistent chemicals may

be used from the air in sev-

eral ways. They may be re-

leased from tanks carried in

the bomb racks and under

the wings of airplanes, or

placed upon an enemy area

by means of chemical bombs,

which are simply dropped

and explode either in the air

or upon contact. Two types

of tanks are in use the

sprinkler, from which the

and the spray type, from which the chemical

runs out in a stream and is broken up by

the air stream of the fast-moving airplane.

It falls upon the target in the form of an

enveloping spray or mist.

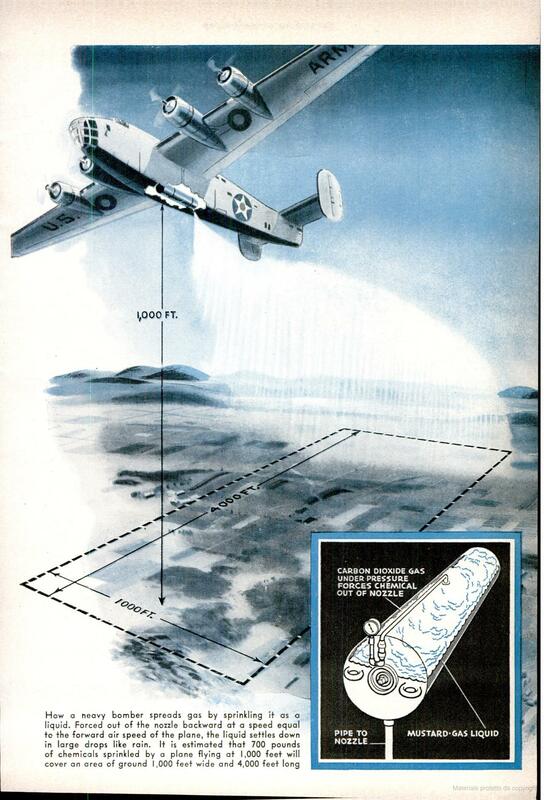

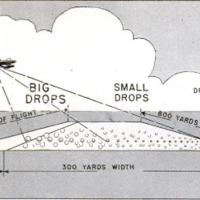

When the sprinkler type is employed in an

attack, the liquid is forced backward out of

the tank by a propellant, usually carbon

dioxide gas, at a speed roughly equal to the

air speed of the plane. This makes it fall

straight down in large drops about the size

of rain drops, and little vaporization occurs

until it hits the ground.

The principal disadvantage of the sprin-

kler method of disseminating gas from air-

planes lies in the fact that it is difficult to

predict where the drops will fall, for the fall

depends upon the speed and direction of the

wind at various levels. Under favorable air

conditions at night it should be possible to

hit a target such as a large industrial dis-

trict from altitudes up to 10,000 feet. At

altitudes of 2,000 feet it will not be difficult

to hit a small area such as a railway termi-

nal or junction.

It is estimated that from 1,000 feet with

an average wind velocity of 30 miles an

hour, an area 1,000 feet wide by 4,000 feet

long can be covered by about 700 pounds of

chemicals by sprinkling. The width of the

area covered increases with the altitude

from which the liquid is dropped, and also

with the wind velocity. The greater the area

covered, however, the less concentration on

the ground.

The sprinkler-type tank is comparatively

heavy and cumbersome; is suitable only for

medium and heavy bombers. On the other

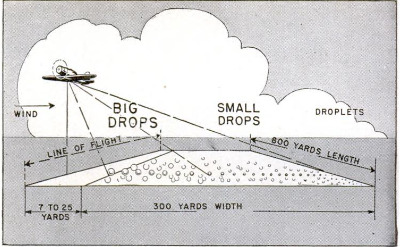

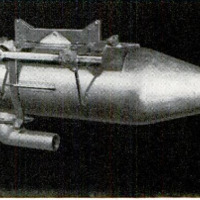

hand, the spray-type apparatus, which is

the standard means of dispersing chemicals

from the air and is the most effective means

of chemical warfare, is simple and light.

Equipment for a light bomber consists of

four streamlined tanks, each holding about

22 gallons and weighing approximately 50

pounds empty, fastened to racks underneath

the wing. When the discharge line is oper-

ated in flight by electrical means controlled

by the pilot, the chemical runs out of the

tank and is broken by the air blast into a

finely atomized cloud of droplets, which fall

to the ground forming a rectangular pat-

tern. The larger drops fall almost under-

neath the plane, while the small ones are

carried farther down-wind. The length of

the pattern is the distance that the airplane

has traveled during the time the tank was

being emptied. The higher the airplane and

faster the wind, the wider the pattern. A

wind at right angles to the line of flight

gives a wider pattern than a parallel wind.

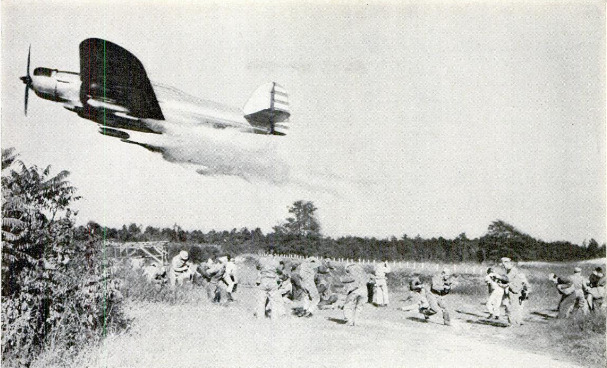

The British believe, according to one of

their official gas-defense publications, that

“spray attacks from a height may be de-

livered by the enemy at such a distance from

the target that the aircraft concerned can

neither be seen nor heard.” There is no

doubt that chemical spray is a practicable

and powerful weapon at high altitudes. But

it was developed primarily for low-altitude

attack, and is most effective at from 75 to

150 feet.

At these altitudes, with a wind speed of

from five to 15 miles an hour, an area about

half a mile long by about a quarter mile

wide may be covered by one of the four

tanks. One airplane, releasing two tanks at

a time, generally covers about a mile. The

entire area thus covered is contaminated by

vapor and droplets of

chemical. Since the agent

has been finely atomized,

evaporation is rapid by

this method, and the im-

mediate concentration of

gas in the air is high. The concentration of

mustard vapor obtained by spraying, for

example, is greater than that obtained by

any other weapon, the effects are produced

more quickly, and the toxic possibilities of

the agent are more completely realized. The

vapor at the time of spraying and for some

time afterwards will affect all personnel in

the area actually contaminated, and even

for a distance down-wind at least equal to

the width of the area sprayed.

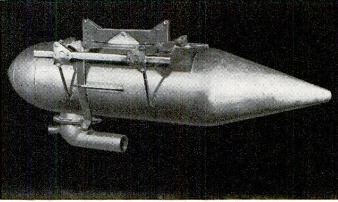

The persistence of gas thus discharged

upon an area, however, is much less than

that of the same gas disseminated by means

of the airplane bomb. Where contamination

for long periods with mustard-type agents

is required, the chemical bomb dropped from

planes will be found more useful than the

spray. Three such weapons are now avail-

able to the United States Army—the 30-

pound standard bomb, the 30-pound thin-

case bomb, and the 100-pound thin-case

bomb.

In searching for a more effective bomb, it

was found that a tin can filled with mustard

gas, and dropped from low altitudes at high

speed, gave excellent dispersion of the liquid

mustard. Such a device, however, had a

number of faults and there has been de-

veloped the thin-case bomb, nearly 80 per-

cent of which is active chemical. When

dropped from high altitudes a bursting

charge fired by an instantaneous impact

fuse is used to prevent the bomb burying

itself in the ground and so losing much of

the mustard. When dropped from low alti-

tudes on hard ground the bursting charge

is not used, and the dispersion of the gas is

obtained by the thin-case bomb breaking up

on contact with

the earth, If gross contamination is de-

sired in a small area such as a bridge or a

railway junction, the 100-pound thin-case

bomb, which scatters the chemical over a

radius of about 40 yards, may be used.

The Spaniards dropped a few mustard

bombs from airplanes upon the Riff tribes-

men in Morocco in the spring of 1925. There

have been rumors that gas once was used

from the air by the British in Afghanistan,

and by Russian flyers in Turkestan soon

after the first World War, but it has not

been possible to verify either of these in-

stances. The Italians are known to have

used mustard gas from aircraft in the

Ethiopian War in 1936, with great effect.

The purposes of air chemical attack are

to create casualties to hostile personnel; to

contaminate hostile areas, such as air-

dromes and important ground, and deny

their use to the enemy; to contaminate ene-

my material and supplies, such as airplanes,

bombs, ammunition, and food; to threaten

hostile equipment and personnel and thus

delay operations and require the enemy to

carry means for protection and decontami-

nation; or to cause damage by fire.

‘The possibilities of incendiary bombs have

been thoroughly explored during the present

war. Scarcely a bomber takes off today on

a hostile mission without some share of its

load being taken up by incendiaries. The

most widely used of these weapons is the

small magnesium bomb. The Germans have

one weighing 2.2 pounds, their so-called

“electron” bomb, and the British use one

that weighs about four pounds.

The typical small bomb of this type has

a body of magnesium alloy and sufficient

thermite filling to burn intensely and ignite

the magnesium body when fired by a simple

impact fuse. They are generally dropped in

clusters, or within a large bomb case which

opens in mid-air—the famous Molotov bread

basket of the Russians. By this means the

baby bombs are scattered over a wide area.

They burn fiercely, developing a tempera-

ture of approximately 4,000 degrees F., and

will ignite anything combustible with which

they come in contact.

These small incendiaries are much more

efficient for general purposes than the large

oil bombs which have been used in Europe.

The latter contain as much as 16 gallons of

oil and produce a tremendous amount of

heat, but are so large that only a few of

them can be carried. Small oil bombs should

prove more effective, and their use may be

expected.

-

Autore secondario

-

Col. Alden H. Waitt (article writer)

-

Lingua

-

Eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1942-06

-

pagine

-

102-105, 216

-

Diritti

-

Public domain

-

Archived by

-

Sami Akbiyik