-

Titolo

-

America's artillery might

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: America's artillery might

-

extracted text

-

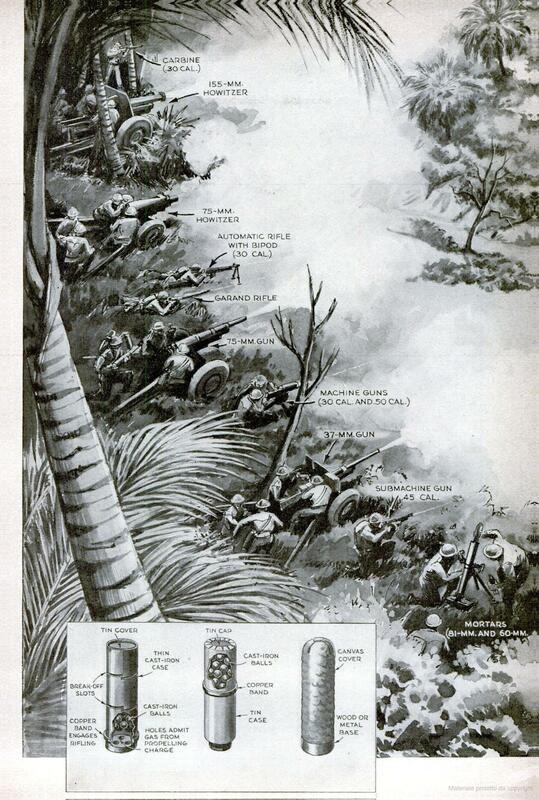

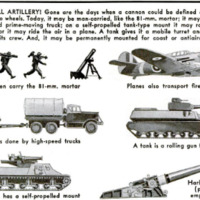

WE HAVE been hearing so much of

planes and tanks that the artillery

arm has been shoved into the publicity

background. Just the same, artillery re-

mains very much in the forefront of prac-

tical military thinking, and there is no sign

that it will diminish in importance as planes

fly faster and tanks get bigger. For that

matter, what is a bomber but a piece of fly-

ing artillery, with gasoline and gravity

propelling the projectile instead of gun-

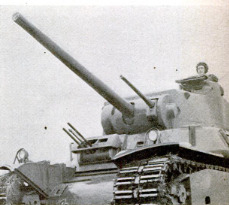

powder? And when you mount a cannon

on a pair of caterpillar treads and surround

it with armor and a few machine guns for

close-up protection, isn’t it still a cannon?

For the present purpose, however, we

need not take in that much ground. Limit-

ing the argument to artillery in the con-

ventional sense, let us consider the composi-

tion of a typical German armored division.

Its chief striking power, of course, comes

from its tanks. But behind the tanks one

always finds a regiment of motorized artil-

lery, equipped with 105-mm. pieces, and

150-mm. as well. (25.4 mm. = 1 inch.) Like-

wise an antiaircraft-antitank battalion with

20-mm., 37-mm., and 47-mm. guns, usually

on self-propelled armored mounts. Artil-

lery protects the tanks during the assembly

period—nothing is quite as vulnerable as a

parked tank, unless it is an airplane on the

ground. During the attack an artillery

liaison officer rides in a tank in close prox-

imity to the tank battalion or regimental

commander. When anything untoward hap-

pens, such as the sudden discovery of an

antitank battery in a tankproof area where

it can fire on the flanks of the advancing

column, there is an immediate call for the

artillery to silence the AT guns from a safe

distance. Clearly, as far as the redoubtable

Nazi panzers are concerned, artillery is far

from an outdated arm.

For holding ground, and for a great deal

of ground-gaining, the Germans, like other

nations, still rely largely on infantry. What

then is the relation of artillery to infantry

in this, still the most successful of Euro-

pean armies in spite of its recent reverses?

“In the German Army,” writes one of their

colonels, “it is fundamental that no infantry

attack is to be carried out without artillery

support.” A German infantry regiment is

equipped with 12 AT guns, 27 two-inch

mortars, 18 three-inch mortars, six 2.95-

inch guns, and two 5.9-inch guns. The

divisional artillery is equipped with 36 105-

mm. howitzers, 12 150-mm. howitzers, and

other large pieces. Artillery observers stick

close to the infantry commander, maintain-

ing contact with their batteries by radio

and supplying help promptly wherever

needed.

Our own Army has studied the lessons

of the European campaigns very carefully

and here is the result as far as artillery is

concerned: The square infantry division

(four regiments) is supported by a field-

artillery brigade of three regiments which

carries 48 105-mm. howitzers and 24 155-

mm. howitzers. The triangular infantry

division (three regiments) has proportion-

ate numbers of the same weapons. The

armored division supports its 390 tanks

with 57 60-mm. mortars and 27 81-mm.

mortars, as well as 194 37-mm. towed AT

guns; 42 75-mm. and 54 105-mm. howitzers,

all self-propelled. Obviously our general

staff relies on artillery to a considerable

extent to win the war, and it is scarcely

likely that American artillerymen will have

any reason to complain that they are in a

branch of the service where a man has no

chance to show his mettle.

All the weapons thus far mentioned were

used in World War I. That is, the calibers

and classifications were the same. But

when we examine the individual pieces in

more detail, we find a great improve-

ment in fire power, mobility, and ac-

curacy. The rate of progress is not

as striking as in the case of the air-

plane, but then the airplane is not yet

50 years old, while cannon date back

to the thirteenth century.

The humble but invaluable trench

mortar is a good example of the ad-

vances made in the last 20 years. A

mortar is simply a light steel tube set

on the ground pointing skyward, and

supported in front on two legs, form-

ing a tripod. Usually it is muzzle-

loaded: the shell is dropped into the

tube, the propellant charge in the

base of the shell is exploded by a fir-

ing pin, and the projectile sails out

considerably faster than it went in.

But not very fast as shellfire goes—if

a modern pursuit plane took off from

the muzzle at its normal speed just

ahead of the shell, the latter would

not quite catch it. The trajectory

of the mortar projectile is like a lob

in tennis, high and slow, and, like the lob,

it can be extremely annoying when well

placed.

The familiar Stokes mortar of the first

‘World War proved that much, in spite of

the fact that, being a smoothbore weapon,

it had no means of preventing the projectile

from tumbling end over end on its course.

This not only increased the drag and short-

ened the range, but, since no two projectiles

tumbled in the same way, dispersal of

shots was great. The modern mortar fires

an elongated, tear-shaped projectile equipped

with tail fins to keep it pointed on its

course. As a result of this and other im-

provements, it has become a much more

formidable weapon. The following table

shows how it compares with the World

‘War I model:

Trench Mortars

in. Stokes 60-mm.M-2 S1-mm. M-1

‘Weight of projectile, (3.24n.)

pounds 12 3 6.9 and 15.01

Maximum range. yds. 750 1.935 3,290 and 1,275

Weight of mortar in

firing position, pounds 110 “2 136

Thus the modern 81-mm. mortar, with

caliber slightly larger than the Stokes and

firing a projectile 3.01 pounds heavier, has a

range 70 per cent greater, and higher ac-

curacy for a given range. At the same time

the piece is only 26 pounds heavier. The

smaller 60-mm. mortar, with a range of

over a mile, weighs 42 pounds and can be

carried by one man. With all the other

developments simultaneously taking place,

one can never predict how important such

improvements may prove to be in a modern

war. A light cannon is just what the doctor

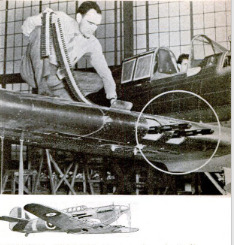

ordered for air artillery. Each German

parachute battalion is liberally equipped

with 75-mm. guns, 8l-mm. mortars, or

mine-throwers, as the Germans call them,

and an abundance of 50-mm. mine throwers.

This is in addition to each parachutist’'s

personal armament of automatic pistol,

hand grenades, and dynamite sticks. !

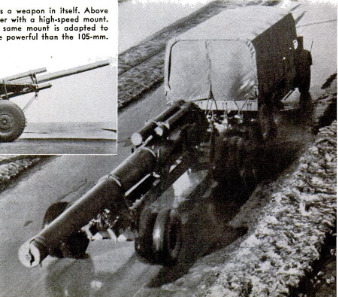

The larger cannon classed as field artil- |

lery likewise reflect the results of research

in ballistics, gun manufacture, the chem-

istry of explosives, and all the other techni- |

cal arts that go into armament production.

Field pieces are divided into guns and how-

itzers, the latter being distinguished by |

their short barrels and higher elevation. |

For a given caliber the gun will have a |

longer barrel, higher muzzle velocity, and,

as a rule, longer range. The distinction

between the two types is becoming less |

sharp as gun elevations increase, while at |

the same time howitzers are acquiring

higher muzzle velocities and longer ranges.

One consequence is that the 105-mm. how-

itzer is now largely replacing the 75-mm.

gun in our Army, in spite of great improve: |

ments in the latter. A 75-mm. gun of 1918

design was limited to a six-degree traverse

or side-to-side swing without shifting the

trail. By means of a_split-trail arrange- |

ment the traverse has been increased to 85

degrees, or almost a right angle, and the

maximum elevation has gone up from 19 to

45 degrees. Partly through the higher ele-

vation, the range has been increased from

9,700 to a maximum of about 13,000 yards, |

and mobility has been greatly improved by

mounting the piece on a high-speed car-

riage. But the 105-mm. howitzer is prac-

tically as mobile; it weighs 4,300 pounds— |

only 500 pounds more than the 75-mm. gun,

and can be towed by a 2 1/2 -ton truck. Fir.

ing on its own wheels, it is practically

ready for action when it stops rolling. It

has about the same range as the 75-mm.

gun, but the big advantage of the howitzer

is that it throws a 33-pound projectile in-

stead of the 15-pound shell of the 75. A

piece which can deposit twice as much TNT

on the enemy per shot is obviously to be

preferred, and that is why the 105-mm.

howitzer is getting a bigger share of the

business in the present war.

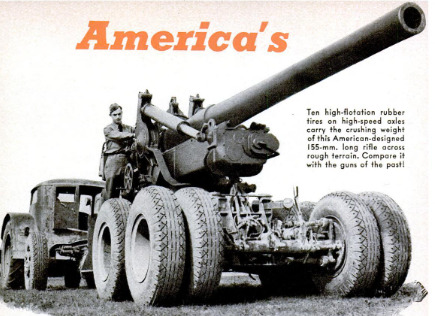

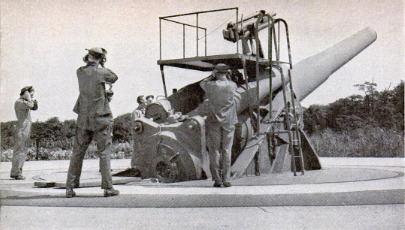

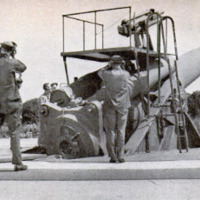

For more oomph, the artillery goes up to

the 155’s. The howitzer weighs only 9,000

pounds and, equipped with air brakes and

pneumatic tires, can be drawn by a truck

at 50 m.p.h. on a good road. Once it gets

there it can be emplaced in a few minutes.

The 155-mm. howitzer fires a 95-pound shell,

as does the gun of the same caliber. The

gun has double the range—25,000 yards as

compared with 12,400 for the howitzer.

This gun is really a heavy piece—15 tons—

and it requires a truck or tractor of about

the same weight to move it. Beyond the

155's we get into the really big field artil-

lery, like the 8-inch and 240-mm. calibers,

some mounted as railroad guns.

One might imagine that guns weighing

10, 20, and 40 tons with their tractors, and

necessarily presenting problems when it

comes to crossing bridges, traversing under-

passes, traveling on two-lane roads, etc.

would have been superseded by the bomber

by this time. But once a big gun has been

strategically sited and has got the range it

can pound a target with an accuracy far

exceeding that of the best bombers. As a

siege weapon against cities and fortifica-

tions it still has no equal. It can make a

vital enemy position absolutely untenable

and do terrible damage to any body of

troops which tries to stand up against it

without equivalent fire power.

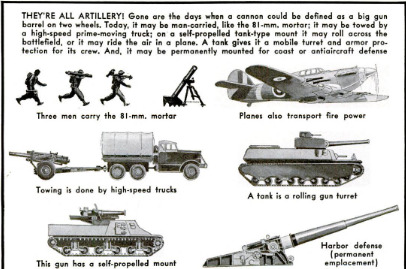

The allocation of artillery to bodies of

troops is something like a banking system.

The smallest pieces are part of the organic

equipment of platoons and companies of

infantry. The 105 is a divisional arm, the

155 both division and corps. Bigger guns

are assigned by GHQ as required. GHQ

would correspond to the Federal Reserve,

the small infantry units to the country

banks; in between there are the metro-

politan banks with their larger resources.

Any group may requisition or borrow ar-

tillery from a higher echelon—if it can get

it. As in the money market during a

financial crisis, the would-be borrower does

not always find a willing lender. |

The advances in field artillery, notable as

they are, have been overshadowed by ad-

vances in antitank and antiaircraft guns.

This was a matter of military necessity. |

Every weapon has its counterweapon, and

the development of one compels the devel-

opment of the other. In the first World War

it was found that the machine gun had |

made the defense too strong. Infantry

could no longer advance except at fearful

cost. The tank was evolved to cope with the

machine gun. The antitank gun was then |

pitted against the tank.

Actually the surest defense against the |

tank is another tank, preferably a bigger

one. But an antitank gun costs only about |

a tenth as much, in manpower and ma-

terials expended in manufacture, and thus

fills a definite need. Since it often accom-

panies infantry it must be as light and

small as possible. The effective range need

not exceed 1,200 yards, but the trajectory

must be flat so that tanks cannot roll

underneath as they close in. A flat tra-

jectory means high muzzle velocity and a |

relatively small shell.

The 37-mm. AT gun, which represents a

good compromise between these require- |

ments, is mounted

on a carriage of the split-trail type, which

affords a wide traverse without shifting the

mount. The weapon is easy to aim and op-

erate. It is normally designed for visible fire

and direct laying or aiming: the gunner,

that is, has direct control of the weapon and

does not rely on any mechanical device to do

the pointing for him. “The rate of fire is 15

to 20 rounds a minute under combat con-

ditions.

The 37-mm. gun is effective against light

tanks. It cannot stop medium and heavy

tanks unless it scores a hit through an open

port, or damages a tread or track suspen-

sion. For protection against these larger

tanks a 75-mm. gun is needed. The biggest

tank so far built can be disabled by a well-

placed shell from a 75-mm. gun.

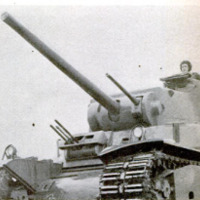

‘When mounted on a tank chassis or half-

track weapon carrier, and provided with a

shield for the crew, either the 75-mm. or

37-mm. gun is called a “tank destroyer.”

The combination really constitutes a tank

in which armor protection has been sacri-

ficed for lightness and speed. Such a vehicle

must traverse rough terrain, plow through

soft places, ford streams, climb out of

ditches and shell holes, and in general

cover ground almost like a horse. The

chassis must not be so low that it will

strike ordinary obstructions, nor so high

that the body will present an easy tar-

get. The power plant must be big, the

armor as heavy as possible, yet the combi-

nation must not be too heavy to get around

‘with speed and certainty.

very low silhouette to make it hard to hit.

A jeep or an armored half-track might

take a shot with ordinary gun sights at a

low-lying plane and bring it down, but

that would be something to write home

about. For antiaircraft work, special guns

and aiming means are employed, because

the target is moving so rapidly that the

unaided human eye and brain are inade-

quate. The essential difference is in the

method of fire control—of which more later

—rather than in the gun itself. Thus the

antiaircraft battery can be and often is

used against tanks and armored cars with

great effectiveness. In fact, the service

regulations require the crew to be prepared

for such operations. But, while an AA gun

automatically becomes an AT gun when

the muzzle is pulled down and it i aimed

by eye, an AT gun cannot be used for AA

fire uniess it ls especially equipped for that

service. We now have some 37-mm. guns

on half-track carriers which are so equipped

and can bo switched instantaneously from

AT to AA shooting.

The standard sizes of AA guns in our

Army at the present time are 37 or 40-mm.,

3-inch, and 90-mm. for mobile service. Still

larger guns are being manufactured for use

in semifixed emplacements. As always, the

design requirements conflict. An AA gun

should have a high rate of fire, high muzzle

velocity, as straight a trajectory as possi-

ble, the lowest possible time of flight, and

large bursting area for the projectile. But

an the size of the gun increases the rate

of fire drops. Likewise, high muzzle ve-

locity requires a thick-walled shell, which

reduces the burst effectiveness. Mobility

calls for a small gun and high-altitude ef-

foctiveness for a big one. The result is that

no one gun will fulfill ll the requirements,

and several calibers and types are necessary

10 do the job right.

For low-flying planes—say up to 5,000

feet—the 37-mm. or 40-mm. gun is reason-

ably effective. The latter is the famous

Bofors funnel-shaped design which has

been thoroughly tested in Europe. It is

fully automatic and fires up to 120 rounds

a minute. The projectile weighs 2.2 pounds

and will explode on contact with an air-

plane wing. The muzzle velocity of 2,850

feet per second gives the gun a virtually

straight trajectory to a range of about

9,600 feet. The weight of the gun happens

to be the same as that of the 105-mm. how-

itzer—4,300 pounds—and it can be put into

action within half a minute after arrival

The next larger caliber, 3 inches, makes

a much heavier AA gun-—12,000 pounds—

but one which is still readily transportable.

Set up, the gun, mount, and working plat-

form rest on four sectionalized outriggers or

horizontal girders laid on the ground. This

contrivance folds up for transportation and

takes from seven to ten minutes to em-

place. The muzzle velocity is almost as

high as that of the Bofors, but the rate of

fire is down to 25 rounds per minute. On

the other hand, the projectile weighs over

five times as much—12.7 pounds. A gun

of this caliber is reasonably effective up to

15,000 and possibly 18,000 feet. It is valu-

able in the field and for protection of tar-

gets requiring precision bombing.

The data on the larger AA guns, 90-mm.

and 4.7-inch, is restricted. However, it is

safe to assume that our 90-mm. is superior

to the German 88-mm. gun, which fires 20

rounds per minute and has an effective al-

titude of about 25,000 feet. The 90-mm.

gun travels on a single-axle trailer, towed

by a six-ton truck. It is the largest mobile

size in AA guns. The 4.7-inch is too heavy

to be considered fully mobile. A gun of this

caliber, intermediate between the 105 and

155-mm. field piece, is heavy and expensive

to build, and expensive to fire, but one of

its shells may dispose of a plane several

hundred feet from the bursting point, and

the bursting point is somewhere up in the

substratosphere. Where a gun like this is

emplaced, the bombers fly high and bomb

less accurately, if they bomb at all.

One thing the machine cannot do, how-

ever, and that is to make the decisions. That

1s still a man’s job. The greater the extent

of military mechanization, the more impor-

tant intelligence, will, initiative become.

And in these qualities the artillery arm

ranks high. There is nothing more impor-

tant than artillery in this war—unless it is

the artilleryman.

-

Autore secondario

-

Carl Dreher (article writer)

-

Lingua

-

Eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1942-07

-

pagine

-

54-60, 210,212,215

-

Diritti

-

Public domain

-

Archived by

-

Sami Akbiyik