-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Precision bombing tanks teamwork

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title:

Precision bombing tanks teamwork

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

WHEN you hear the men on the far bat-

Wee fronts calling for planes and more

planes, just remember that what they really

are asking for is combat teams and more

teams—equipped with fighting airplanes, of

course.

The efficient operation of a bombardment

airplane involves one of the most intimate

mergers of personality ever attempted or

achieved by seven, eight, or nine aggressive,

hard-hitting, individualistic American

youngsters. This suppression of ego and

merger of fighting men into a single combat

organism is so basic and well understood by

military flyers that they hardly even men-

tion it when they call for “planes.” But its

necessity should be understood by us lay-

men, too, lest we jump too easily to the con-

clusion that bombers are ready for aggres-

sive action as soon as they roll off the as-

sembly lines.

This sobering thought is the product of

several days spent talking with bombard-

ment men up and down the Atlantic coast.

These men are the nucleus of America’s hit-

ting power, and they are eager to get at the

enemy and smite him. But throughout these

talks ran one theme—the urgency, the nec-

essity of developing a combat team for

every plane.

The kind of men who fight with airplanes

do not talk easily about their intimate per-

sonal relationships. It was difficult to get at

the simple details of what their teamwork

implies, and the details they did point out

were generally negative. As in marriage,

the happy combination goes along smoothly

and uneventfully; it is the unsuccessful re-

lationship which causes talk.

“It's this way,” said one Flying Fortress

pilot. “If I don't like the color of my bom-

bardier’s eyes, or he doesn’t like the cut of

my jib, we just aren’t going to get very good

results, that's all.”

And then, completely unaware, this pilot

proceeded to give me a dramatic demonstra-

tion of the subject.

He had just brought his plane back from

a patrol mission hundreds of miles over the

Atlantic, hunting for submarines and sus-

picious vessels. It was a six-hour mission

and they had returned an hour and a half

late. There was a pea-soup fog that morn-

ing, and it had been a tense and difficult day.

The pilot had landed his four-engine ship,

carrying full bomb load, and with a low

ceiling.

I gathered that the difficulty had been

with navigation. On the best day, naviga- |

tion is difficult on this kind of mission, for

you are frequently circling ships and other-

wise changing course to complicate the cal-

culations. It had been especially tough in |

this day’s fog. |

“We'll be all right,” said the pilot, “when

our navigator gets a bit more experience.”

There it was. I knew, but the pilot did not |

yet know, that the navigator was quite as

experienced as this pilot, if not more so. For

six months he had been navigator for one of

the best bombardment pilots in the Ameri-

can Army. He was accus-

tomed, of course, to the ways

of the pilot with whom he

had been training.

Here were two good men

who, in the process of ex-

panding the Air Forces and

reorganizing a squadron, had

been put together for the

first time. In a few days, or a few weeks,

they would learn each other’s peculiarities,

learn to work together as a team. In the

meantime, if you tried to send them out on

a difficult bombing mission, it would be a

fairly good bet that you would not hit the

enemy effectively. On the other hand, you

might very easily turn a fine ship and some

splendid young fighting men into scrap

metal and monkey meat.

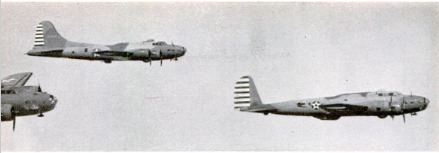

America has staked her future on the

striking power of the most complex weapons

ever known to man, and of these the prime

example is the heavy bombardment plane.

Everything depends on our ability to hit the

enemy where he lives. But as the great

ships, the B-17’s and the B-24’s, come from

the factories in increasing numbers, they

are not yet ready for combat—not by a long

shot. They will be ready after they have

been manned by trained men who have been

able to blend themselves into the intimacy

of a family.

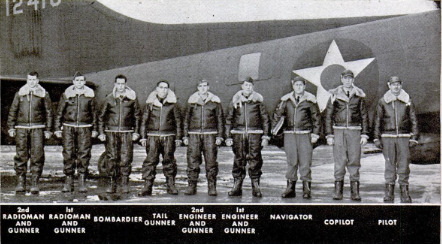

If you leave out the ground crew of two

maintenance men for each engine, on whom

all safety depends, the combat team for a

four-engine bomber consists of nine men;

pilot and copilot, navigator, bombardier,

radioman with assistant, aerial engineer

with assistant, and (in the newest planes) a

rear gunner. All the last

five must double as gunners,

ready at any moment to

step into the breach if an-

other man is incapacitated.

Talk to the old-timers and

they all tell you the same

story of interdependence, al-

most as if they had learned

it by rote:

The navigator gets you

there. In some of this last

year’s bombing over Europe

the bombs have landed as

much as five miles away

from the target. If anything

like that happens, you might

just as well never have

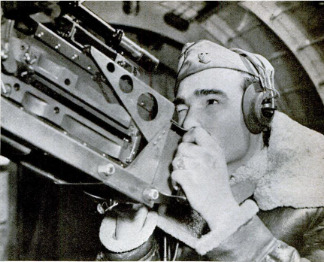

started. The bombardier

drops the bombs. While he

aims he controls the ship.

All of Captain Colin Kelly's

courage and skill would

have gone to waste, as he

maneuvered at 23,000 feet

over the Japanese battle

ship Haruna, if his bom-

bardier had not been able

to lay those three eggs where

they could sink the ship.

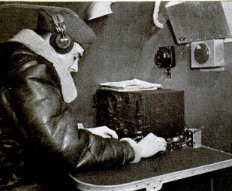

The radioman must be on

the alert. If he misses a weather message,

the whole flight may fail. The engineer

must know every rivet in the plane, and

every circuit in its miles of electric wire. If

something goes wrong, and he fails to tell

the pilot, then everything may go wrong.

And when the pursuit planes start swarming

around, every one of these men in the rear

of the plane must be able to handle a ma-

chine gun and shoot straight. Otherwise it

would be just as well if they never had

started. Or if the plane hadn't been built |

in the first place.

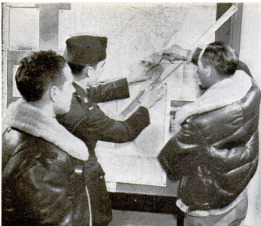

Through teamwork, processes involving

precise calculations are reduced to simple,

well-understood routines. When the ship

takes off, for instance, one of the first things

the pilot wants is a double drift reading to

determine his true ground speed. As the

pilot runs a straight course, the navigator

looks down through his gyroscopic drift in-

dicator, an optical instrument with its field

of vision crossed by straight parallel lines.

Picking a stationary object on the ground,

the navigator turns his lens until the object

seems to move straight along the parallel

lines, then takes a reading on a circular

scale. For the double drift, the pilot turns

45 degrees off the course for a minute, then

turns at right angles for another minute,

then another 45-degree turn back to the

course. From observations on these courses,

it is possible to determine the effects of wind

and ascertain the actual ground speed from

the indicated air speed. But how does the

pilot fly his ship? How

sharply does he bank?

Does he take his double

drift to the left or

right? Does he want to

do it en route, or make

the reading first and

then start out from a

given point? For ac-

curacy and smoothness

of operation these two

men have to understand each other very

well.

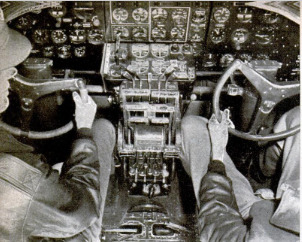

All executives are dependent on sub-

ordinates, but especially so is the pilot, who

must guide his motored projectile for hun-

dreds of miles and strike within a few yards

of a specific point. The captain of a battle-

ship has time to check over his navigators

work, if necessary; not so the pilot. He has

to take the navigator’s word.

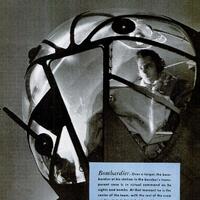

Down in their cubbyhole below the pilots,

the navigator and bombardier have their

own teamwork. On the long voyage over,

the bombardier has little to do, but he must

be fit for his crucial moment. All at once

he may be terrifically busy, making obser-

vations and all the corrections he has to

make on his instrument. It's a help if he

can take a drift reading from the navigator,

instead of making it himself.

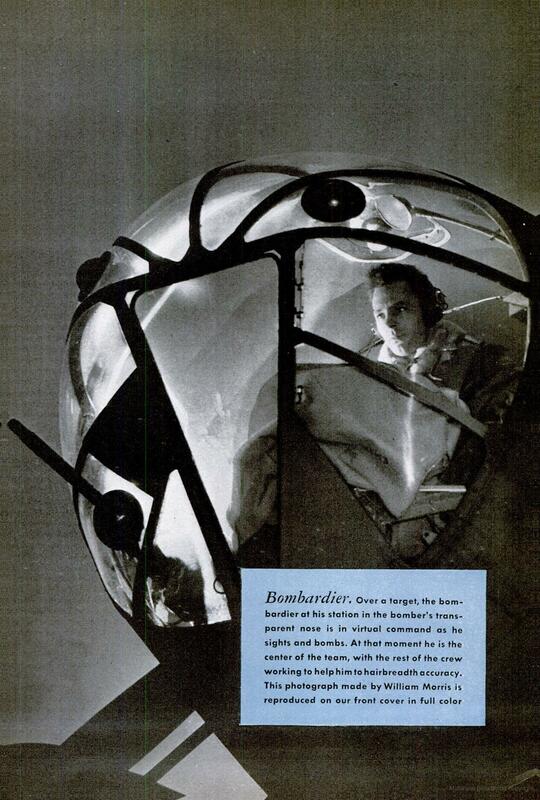

The pilot's dependence reaches its utmost

at the supreme moment. At last the ob-

jective comes near.

And here is where the cobrdination of the

team finds its best expression. No more

than five words are spoken, perhaps not

that many. Conversation under stress, es-

pecially at high altitudes, is too wearing and

often unintelligible. Instead, the men com-

municate over the interphone system in a

series of well-practiced, prearranged clicks

—standardized and memorized at a bom-

bardier school. Each man knows what he

has to do, and trusts the other to do his

share. The pilot, except in extraordinary

circumstances,

leaves the bombing to the bombardier. It

is the bombardier who arms the bombs,

opens the bomb-bay doors, and drops the |

bombs. The mission accomplished, the pilot |

listens for two spoken words: “Mission |

complete.”

Until then, everything is in the bom-

bardier’s hands. In a very real sense he is

in command of the ship while he sights and

bombs. The pilot works for him. [

At this point everyone in the plane is con-

centrating on one specific purpose—to help

the bombardier to hairbreadth accuracy.

The gunners may be blasting away at enemy

pursuits, the pilot coolly keeping the plane

on its steady course, the copilot filling in for

the pilot's needs without being told, like a

good private secretary. If any one fails, it is |

failure for all.

All warfare is national teamwork. An

army is a team made up of combat teams. |

And there is nothing new about the neces- |

sity for teamwork in a bomber. In the Ger- |

man air force, if one man of a bomber crew |

is lost, the whole crew goes back into train-

ing, out of action until its new member has |

been broken in. That is the ideal we strive |

for in our own Air Forces, too. [

Our own Air Forces are perfectionists. |

Up until a couple of years ago a pilot had

to have 2,000 hours of military time before

being intrusted with the controls of a For-

tress. Today Fortresses are being flown by |

downy-cheeked boys, and there will be

thousands more of those kids on the job be-

fore long. To multiply the Air Forces with-

in a year or so, far more than a hundredfold,

will necessitate speeding up the old princi-

ples. But one thing they can't afford to com-

promise. That is the necessity for these

young and experienced men, pilots, navi-

gators, bombardiers, radiomen, and gunners,

to break in together and form cohesive

groups which work together smoothly, un-

derstand each other perfectly, who operate

like nine musketeers—"all for one and one

for all.”

Plenty of men in the first World War were |

given instruction right behind the battle

lines, in how to use their rifles, and went

into action without ever having fired a

practice shot. Perhaps some of these un-

trained men were 50 percent effective. |

But you can’t get away with that, flying a

heavy bomber. If one man fails, it's a 100

percent failure for nine men and a priceless

combat machine. [

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Hickman Powell (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

Eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1942-07

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

102-107,202

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

Popular Science Monthly, v. 141, n. 1, 1942

Popular Science Monthly, v. 141, n. 1, 1942