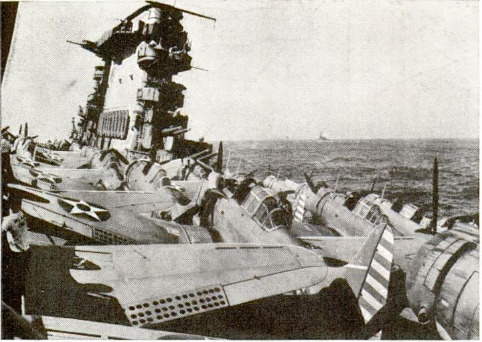

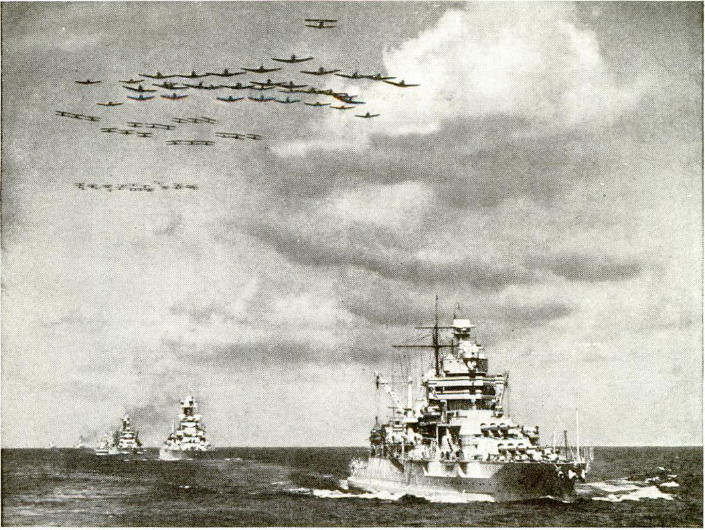

LIEUT. GEN. KOBAYASHI, commander of Japan’s home defenses, wasn't just being an alarmist when he warned his people that they could expect American bombing raids from China or from the American-owned Aleutian Islands at any moment. The U. S. Naval bombers that hit Marcus Island in March had hit close to Nippon. Tokyo began to have jittery nights and blackouts, and the worried General Kobayashi instituted air defense drills in every important community. Then the bombs fell. Tokyo, Kobe, Yokohama, Nagoya felt the first blows of America’s gathering might, and America was electrified by the news. At least a beginning had been made toward the fulfillment of General McArthur’s official report to the War Department, wherein he said: “At the proper time I bespeak due retaliatory measures” for the “repeated, senseless and savage” bombing of the open city of Manila. When he made that report, the immediate reprisal attacks on Tokyo for which Americans clamored were not considered sound military strategy. Unquestionably, though, “at the proper time,” Tokyo and other important Japanese cities will be blasted, bombed and burned - and ultimately exterminated. A beginning has been made. And presumably further preliminary raids on Nipponese territory will be carried out to force Japan to recall some ships and planes to defend her own coasts, reducing the forces available for offensive operations. The successive brilliant assaults on widely separated Japanese-occupied islands by U. S. Navy striking forces under command of Vice Admiral William F. Halsey were thrilling and heartening news to America, Following hard after the smashing naval and air raids on the powerfully armed bases in the Marshall and Gilbert groups came the destruction of 16 out of 18 enemy planes “west of the Gilberts,” a spectacular attack on the previously American-owned Wake Island, and then a raid on Marcus Island - a major stepping stone between Japan and her mandated territory (Nanyo, to the Nipponese), and only 970 miles from Tokyo and 700 miles from her two island bases at Chicha Jima and Saipan. The “task forces” employed consisted of one or more aircraft carriers, each carrying several squadrons of planes, supported by heavy cruisers and destroyers. As Japan still has superiority in the air, particularly over her own islands, it is extremely difficult - though by no means impossible - to dispatch planes (either shore-based or carrier-based) against her vulnerable cardboard cities. Sustained attacks would be out of the question. As carrierbased bombers are limited in both range and bomb-load, the greatest effect of “hit-and-run” raids would be psychological - terrorization of the populace. There are a number of Allied air bases in Central China and near the coasts from which Japan can be bombed, and doubtless will be in good time. However, the other approach to Japan, via the Aleutian Islands, envisages a rapid movement from Alaska down the 900-mile bowspring of the Aleutians to Japan. Without consideration of either the adequacy of base facilities (a vital military secret), the strategic value of the movement or the chance of success - which are the concern of expert war planners - and only as a matter of pure speculation, let us examine the physical possibilities of a combined sea-and-air attack by this route, keeping in mind the fact that this plan is not based on any official knowledge or inside information of what our navy planners are thinking. A glance at a large map, or globe, shows us that the western islands of the Aleutian group are 1,800 miles from Tokyo or 1,600 miles nearer to the Japanese capital than are the Hawaiian Islands (3,400 miles distant); that the distance from Kodiak (site of a naval and submarine base, and keystone of the American North Pacific defense chain) to Dutch Harbor is approximately 500 miles, thence to Attu (the western extremity of the Aleutian group) another 900 miles; that Attu is only 800 miles from the Japanese air base of Paramushiro (northernmost point of the Kurile Islands and near the southern tip of the Kamchatka Peninsula), 1,425 miles from Tokyo. The composition of the attacking force, considering that the intended blow is to be struck with airplanes, undoubtedly would consist of five to seven aircraft carriers bearing some 350 - 400 bombers together with about 75 fighting planes, and a few torpedo planes for protection against any Japanese capital warships which might be encountered enroute. With such a number of carriers, the protecting force would have to be a large and powerful one, and all units capable of making as much speed as the carriers - say two of the new 35,000-ton battleships, six heavy cruisers, six light cruisers, and some 30-40 destroyers, with perhaps a number of submarines stationed along the route as additional precaution against patrolling enemy ships. Big patrol bombers ranging far out over the route from the Alaskan bases would add to the security of the task group, both on its outward and return passages. Secretly assembled at Kodiak and Dutch Harbor, where fueling and other preparations would be completed, this formidable force should move out from its bases and at such speed as to pass Attu about mid- night, thence at 25 to 27 knots on a south-westerly course approximately parallel to the Kurile Islands and at a distance of no less than 750 miles. Meanwhile an umbrella of fighting planes should be maintained throughout the daylight hours, with scouting planes well advanced and on the flanks in order thoroughly to investigate the waters through which the attacking force will pass during the night. If undiscovered, the force should continue on the second day as before and until within about 800 miles of Honshu, the main Japanese island, then head directly for Tokyo arriving, if possible, at a point 500 miles distant about dusk. With the added protection of darkness, all speed should be used in pressing forward for the kill, so as to arrive at a point some 350 miles off the coast about midnight, at which time the furies of hell would be loosed to wing their destructive way, squadron by squadron, toward the enemy’s homeland, - two hours distant by air, - where a devastating and continuous blitz would be maintained for at least two hours. Their mission accomplished, the bombers would wheel away and fly toward their rendezvous with the carriers and escorting vessels (already steaming toward home bases), timing the arrival just at daybreak so as to be able to make safe landings on board. This job completed, the task force would continue on its way at top speed, the protecting umbrella of fighting planes once more raised to keep off enemy bombers which unquestionably would follow. Japanese surface ships could not hope to catch the speedy American task force. Should any be in position to intercept, however, the supporting craft would be able to stand off the attack. The first day of the return trip would be the most hazardous, naturally, then would come the welcome relief of darkness. Beginning with the next dawn the attacking group would be safe from all attack except, perhaps, from lurking submarines enroute. The scouting planes ranging far ahead and on the flanks should be able to spot these and give ample warning of their presence. Thus ends our speculative air raid against Tokyo. Would an actual assault of this na- ture be worth the risk to men, ships and planes? That is a question which only the Navy High Command can decide. Undoubtedly the losses sustained by the American attackers would depend upon the promptness and efficiency of the anti-aircraft fire and of the effectiveness of the opposition from Japanese fighting planes, which latter might not be so formidable because of the large offensive operations being conducted in other theaters of war thousands of miles distant. On the other hand, one can easily picture the destruction that 300-odd bombing planes might wreak upon Japan, to say nothing of the state of mind created in the average Japanese by such a raid. This form of attack has been most feared by them, particularly because of their over-populated cities and their flimsily constructed houses, so vulnerable to incendiary bombs. Japan knows that so long as the Hawaiian and Aleutian Islands are held by the United States as potential springboards, punishing raids by carrier striking groups are pessible and probable, as basically the problem is similar to that which she faced in her attacks against Pearl Harbor, and subsequent successive Allied outposts in the Southwest Pacific. Moreover, weather conditions are propitious now for such attacks, due to the fact that the northern Pacific, tempered by the Japan current, is generally free from fog at this season. Should Russia enter the war against Japan the Allies would have the great advantage of using immediately the air bases of Vladivostok and the Maritime Provinces. This would change the complexion of the problem considerably. American planes could then hop from the Aleutian Islands to Petropavlovsk (Kamchatka), refuel and circle down to Tokyo, 1,700 miles, or use Vladivostok as a stepping stone enroute. These Siberian bases are excellently located, both geographically and strategically, for direct blows on all important Japanese cities - a menace hard to overcome. Meanwhile, periodic harassment of Japan’s widely scattered island outposts probably will be continued and intensified by American hit-and-run task groups, for the purpose of preventing their development into useful bases for Japanese naval and air forces until a full-dress American offensive - land, sea and air - is initiated. As to the route to be taken, every avenue of attack is being given deep thought and study by the American High Command. There is little doubt that before the vast Pacific war is finished the Land of the Rising Sun will have seen plenty of American war planes and fighting ships.