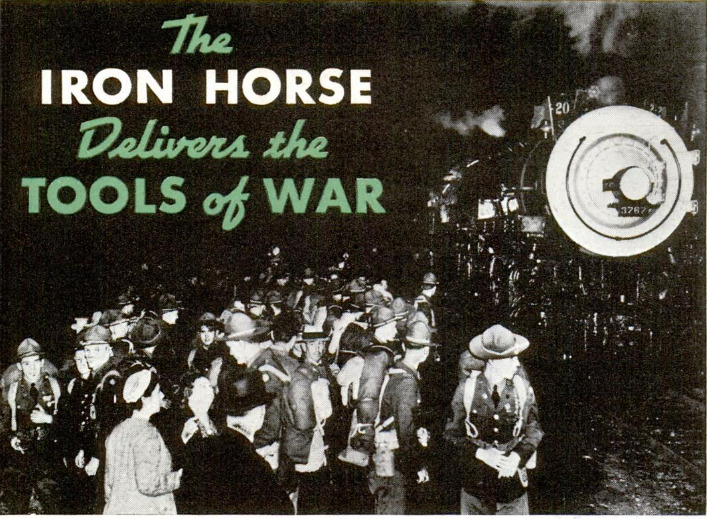

SUREST sign of an impending blitz in Europe is the public notice that passenger traffic on German or Italian railways is suspended or curtailed for the next few days. You can read between the lines - troops and supplies are on the move! There's no such barometer to read in the United States. Unless you were halted at a grade crossing and saw the long strings of flatcars laden with tanks and big guns pass by, or unless you caught a glimpse of the khaki uniforms at every window of the special train flashing westward, you could only guess that America was starting its own big blitz in the days after Dec. 7. But it is no longer a secret that the greatest mass movement of troops and impedimenta and machines of war began within hours after the bombing of Pearl to car Harbor; that 600,000 soldiers and sailors and marines and airmen traveled across the states by railway in the first seven weeks of war with no more interference with regularly scheduled trains than an occasional sidetracking of your Midnight Express to let an army special race through. In round numbers that means that for 49 days, 30 trainloads a day of fighting Yanks moved from camps to bases; and the massing of forces still goes on. Nor does this include the vast number of military freight trains rolling across the land. Full trainloads of bomber and fighter planes, knocked down for shipment but ready for quick assembly, steamed westward from aircraft plants and warehouses of the middle west a day after war broke. As one example of the swiftness of mobilization, within 24 hours of Pearl Harbor a 38-car train laden with prefabricated, portable airport runways passed through Chicago on its way to an untold front. Some of these war freights string out more than a mile from cow-catcher to caboose. When they start rolling, everything else steps out of the way. A regular train arriving in a big classification yard at such a shipping center as Chicago or St. Louis may spend two to eight hours being broken up and remade into new trains; the military freight will skirt the city, pause only long enough to pick up a fresh engine and crew, and be on its way. At the end of its journey the cars are unloaded as rapidly as men and machines and warehouse space permit and put to work again. Idle cars are a luxury neither the railroads nor the nation can afford these days. Are the railroads moving the load? At a time when civilians were taking the train to save their own tires, the biggest troop movement in history took place without serious inconvenience to anyone. Of the entire Pullman fleet of 7,000 sleeping cars, 1,500 have been set aside for troop transport and as many as 2,900 have been assigned to the army on peak days of military travel. As for freight, the railroads last year handled the greatest volume in their history, including virtually a two-year grain crop, without a car shortage. The situation looked rather critical last summer, for the grain elevators were still bulging with a record carryover of 400,000,000 bushels of 1940 wheat when the 1941 harvest came along. Old grain had to be moved out to distant storage points and the new grain moved in. But the railroads assembled a vast fleet of cars and moved the crop in orderly fashion. In one outstanding instance, 500 cars of wheat were hauled from Chicago to elevators in Philadelphia, unloaded and the empties were back in Chicago in less than six days. It isn’t like the days of ’17 and 18, when rail transportation bogged down on the eastern seaboard for want of some place to unload the cars and thousands of loaded freight cars lay idle for weeks and months. Actually, at one time 200,000 loaded cars stood on tracks in the northeastern states, not turning a wheel. Without sufficient ships or warehouse space to take over the cargo, without an efficient system of controlling the government's “priority” freight, cars that should have been hauling goods became warehouses on wheels. One example was the rush order for piling needed at the Hog Island shipyard. Priority tags got the piling there in a hurry, and before anyone was ready to unload them there were 5,000 flatcars loaded with piling sitting in the nearby railroad yards. They sat there, some of them for months, clogging the terminal tracks and unable to get back into useful service. That’s all changed now. Two important agencies born since the first world war - the railroads’ Interterritorial Military Committee and their Car Service Division - are Field and antiair seeing to it that no traffic paralysis can occur again. In general the former cooperates with the Army Quartermaster General in handling troop movements; the Car Service Division is responsible for efficient management of the nation’s supply of freight cars. From Pearl Harbor forward these railway organizations have been on duty 24 hours a day. The Quartermaster General notifies the Committee’s Washington office that a division is to start moving in 48 hours, say from a midwestern camp to Seattle. Immediately wires go out to the regional Committee offices over their interconnecting teletype directing the assembling of 750 to 1,000 cars from the nearest railway centers - in this case perhaps from Nashville, Chattanooga, Memphis, even as far as Chicago, Atlanta and St. Louis. A pool of 50 to 60 locomotives is concentrated at the camp and as many more must be ready to relieve them at a half dozen points on the chosen route to the coast. The mammoth task of diverting all this equipment, manning it, routing it over 2,000 miles of busy rails with scarcely perceptible effect on normal schedules, moving 20,000 men and their personal impedimenta and divisional equipment is an achievement the rails can be proud of. The average troop train consists of 14 to 20 cars; 10 sleepers carrying 39 men each, another for officers, two baggage cars, one for the army kitchen equipment - all military units serve their own meals except the Air Force, which enjoys dining car Juxury - and additional cars for heavy equipment. Artillery units move on freight trains of 10 to 25 cars, with their men constantly guarding their guns and trucks. Smaller groups of men, of course, travel on regularly scheduled trains. One railroad alone moved 200,000 soldiers and equipment. Another was called on to furnish 1,500 flatcars, 286 automobile cars, 200 tourist sleepers and 89 baggage cars to transport one unit. A motorized unit traveled 3,000 miles in four trains assembled on short notice. One division required 64 trains. Early this year the government issued an order which meant that 28,000,000 bushels of corn must be moved by rail. That called for more than 15,500 freight cars. The cars were there at the proper time and place. This was no military movement, but it’s one example of the gigantic tasks the railroads can take in their stride through the “pooled management” of the Car Service Division of the Association of American Railroads. From its 22 offices this Division supervises the movement of loaded and empty freight cars between railroads, anticipates the needs, prevents congestion of loaded cars at the ports or shortages of empties where there’s a load to carry. Before the tremendous grain crop of 1941 matured the Car Service Division ordered eastern and southern railroads to send a huge fleet of empty box cars to the wheat belt, and there was no shortage. In October alone 175,000 cars of grain moved. If unloading facilities at a seaboard terminal are overtaxed - the bogey in World War I - Car Service issues an embargo halting further shipments to that port until congestion is relieved. If a big manufacturer “hogs” idle freight cars on his siding, Car Service embargoes the plant and it will get no more supplies hauled in or products hauled out until it cooperates in keeping the cars moving. Shippers, however, are now cooperating to eliminate the waste of idle cars by rapid loading and unloading. And they have co- operated for nearly 20 years in regional Shippers Advisory Boards which are the “crutch” on which the Car Service Division leans in anticipating freight volume. Every three months these boards gather from their 20,000 member shippers, who load or receive four-fifths of the nation’s freight, information on their expected freight volume in the ensuing quarter. From these reports the Shippers Advisory Boards issue their forecasts of freight movement. Their judgment guides the Car Service Division in providing cars when and where they're needed; and in the last six years they have been right, on the average, within 3% percent. The biggest error in estimate was 6 percent, in one period when an expected strike did not materialize, Even the war, which has given the Car Service Division a 24-hour problem assembling the rolling stock for trainloads of tanks and airplane parts and trucks and petroleum and munitions, did not upset the calculations greatly, for the volume of consumers’ goods is shrinking as the freight of war increases.