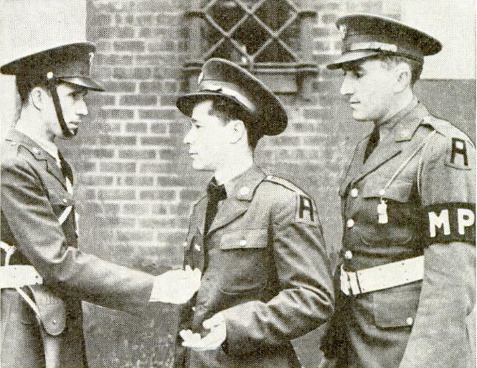

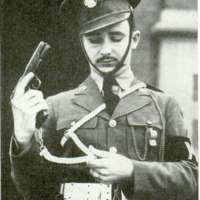

ONE of the developments in the art of war that has been almost overlooked in the excitement of conflict is the evolution of the military police in Uncle Sam’s Army. Today they differ from the gruff and club-wielding “M. P.’s” of the last war as the modern parachute trooper differs from the mule skinner of World War I. On Governor’s Island in New York harbor and at a new school across the Potomac from Washington, thousands of picked men are being educated for special duties and by special methods developed by two officers who started from scratch. The officers, Lieut. Col. Glen T. Strock, Provost Marshal, First Army and Lieut. Col. Harry D. Scheibla, commanding the 518th Battalion, First Army, decided that a military policeman cannot club respect for his authority into a man, but he can impress him with superior intelligence. So, “brains - not brawn” became the requirement. Lawyers have been brought in to teach the men civil and military law and court procedure. Educators have beenborrowed for intelligence tests and New York City policemen for instruction in the psychology of handling people. Expert drillmasters are putting snap and pep into their carriage and step. Crack marksmen teach them to handle their army automatics. Boxers train them to use their fists. Wrestlers instruct them in the art of rough-and-tumble. But, perhaps most important of all is their initiation into the mysteries of body leverage, muscular skill and balance which makes the average unarmed, 1942-style military policeman superior to the average soldier or civilian with pistol, knife, club or fists. Because of these clever tricks of leverage, skill and balance, which were developed from the ancient Japanese art of judo, or jujitsu, one of these super-soldiers can be caught with a gun pointed at his spine or stomach, and by a few quick movements of his body knock the gun aside, close in, wrest it from the aggressor’s hand, and render him helpless. A man with a knife is practically helpless against this new training. By blocking the swing or thrust with a wrist and stepping forward, the military policeman can not only escape being cut, but with a few unexpected maneuvers of the arms and legs, force the knife wielder to drop the weapon or sustain a broken arm. The same is true if the weapon is a club, bottle, orsimilar object. If the attacker uses an object like a chair, as he might in a restaurant or barroom, which prevents the military policeman from getting in close, he is taught to pick up a salt or pepper container, shake a quantity into a hand and toss it into the assailant’s eyes. This invariably stops him. Even should the military policeman find himself flat on his back, he is down but not out. For he has been drilled hours in another trick. As the aggressor leaps on him, he doubles up his knees, meets the assailant with a sudden kick of both feet to the stomach and this sends the surprised aggressor sailing over the M. P.’s head with most of the fight knocked out of him. If the man jumps on a military policeman who has been knocked down, instead of trying to fight from this position, he is taught to grab the man’s shirt front and cradle his knees or feet in the man's stomach. By pushing with his feet or knees and pulling on the shirt, the M. P. tosses him lightly over his head, follows him over and then is on top. And when caught unaware from behind by an assailant who pins his arms at his side, the military policeman has a special set of tricks, too. First he takes a deep breath. This loosens the arms that circle his body. Exhaling quickly, the M. P. slips down and reaches up for the man’s arm, or head, and, bending lower and forward, he tosses him neatly over his head. The resulting crash usually shakes the fight out of an untrained assailant. He is taught how to use hisknees instead of his fists to knock a man out if this last resort procedure is necessary. By one method he twists a man’s wrists until his head is lowered. A quick blow with a knee does the rest. When he is in a desperate plight, the military policeman is permitted to use these trained knees to knock out an assailant’s wind with a quick thrust into the groin or stomach. Other last-ditch methods of stopping a fight are pressure on the phrenic nerves just under the ears and painful manipulation of the muscles of the forearm. Useful as they are, however, these methods are used only when intelligent handling of an emergency has not resulted in peaceful settlement of a difficulty. The men are taught to speak quietly and authoritatively, to avoid argument as much as possible and, above all, to set an example of cool decisiveness in a hot emergency. Subduing recalcitrants, however, is only a small part of the duties of the new military police. They are also used in evacuation of civilians, in handling of communications, reconnoitering and protecting railroad yards and public utility structures used for water, lights, power and communications in war zones, coordination of army and civilian defense forces in battle areas, hunting saboteurs, caring for enemy prisoners as well as keeping order among the soldiers, coding and decoding messages,taking and identifying fingerprints and directing traffic. The last item of duty illustrates how thoroughly the First Army military police are educated, for scores of them have been assigned to the busiest traffic intersections of New York City, where, alongside the seasoned traffic officer of the police department, they learn the tricks of this trade the hard way - under fire. Also, partly as a matter of duty and partly for training, the First Army military police direct traffic on the Governor’s Island ferry and groups of them are stationed at Times Square, Pennsylvania Station and Grand Central Terminal in the big city. In the railroad stations they check soldiers’ papers and tickets, handle the loading of troop trains, keep order among soldiers and sailors, supply information and make themselves generally helpful, both to uniformed men and civilians. Although it is not generally known, a military policeman can arrest a soldier for such apparently minor things as leaving his coat unbuttoned, or his shoes untied or his hat slouchy, or his blouse torn, They seldom do arrest anyone for these infractions, since a warning is usually enough, but a sloppy soldier here and there would have a bad effect on the morale of the army and if the careless habits were permitted in public, the people of the nation would form a bad opinion of discipline in the army. So they are more careful about a soldier’s appearance in a railroad terminal than they would be in camp. And, once more, the new-style military policeman sets an example to the average soldier. As soon as he is selected for this special service, he is issued an extra uniform so that one can always be clean and trim. In addition to standard equipment, he gets the blue and white M. P. brassard which he wears on his arm, his traffic whistle, and white web equipment which sets his uniform apart from the standard army clothing, In seeking men for this branch of the service, preference is given to college men or others who display unusual intelligence, policemen, detectives, firemen, bank guards, armored car guards, state troopers, boxers, wrestlers, athletes or physical trainers. As soon as they are in the service, they undergo a series of mental and physical tests. Passing these, they are put to work on an eight-hour-a-day routine to learn the policing business and get into good physical shape. Heavy emphasis at first is placed upon physical condition and the first half hour of the training day is taken up with calisthenics. An hour or so of close order drill follows, with flying-wedge exercises and formations used to break up rioting crowds. On top of this there is likely to be a period of judo, or leverage and balance training. A typical day’s physical work also includes bayonet practice, education in the use of gas bombs and gas masks and pistol and rifle practice, and any spare time is usually used to play baseball, basketball or some other muscle-building activity. The result is that while many of the new military policemen are small compared to the World War I variety, which tended toward giants and bruisers, they are hard as nails and more than a match for the average man, even without the “brain tricks” which enable them to toss the average man like a bag of potatoes.