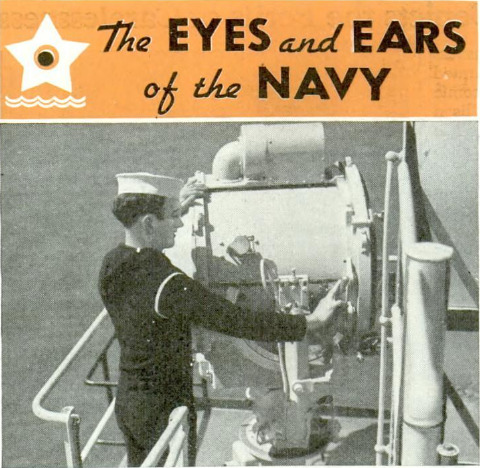

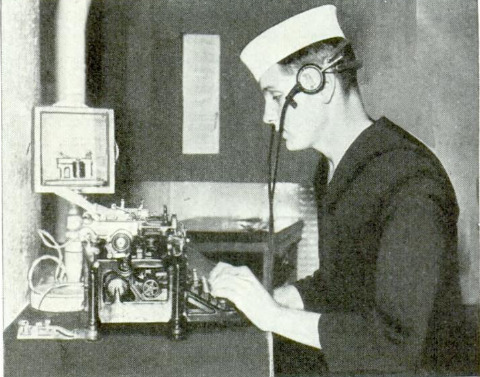

SOMEWHERE off the Maryland coast the American freighter San Gil wallows in the sea, paralyzed by a torpedo that has just crashed into her port side. Two men in the engine room are dead. It is midnight, and 40 men are groping through the black intestines of the doomed ship and feeling their way across the deck to the lifeboats. Out there in the ink, the submarine is taking its time, maneuvering for the kill. The radio has been wrecked by the explosion, but the operator is frantically rigging up an emergency antenna. He has only a few minutes to work, but in those minutes he manages to put a spark of life back in the transmitter and pour a stream of distress signals into the air. Then he climbs into a boat and it pulls away, to watch 11 shells and a final torpedo blast their ship to the bottom. Ashore, a radio monitoring station has picked up the call for help, and instantly the swift communications system of the Navy is in action. By radio and land lines, messages flow to the nearest Coast Guard station and to the Navy Building at Washington, nerve center of the entire Navy. The office of the Chief of Naval Operations is informed of the sinking and another section is consulted as to the position of naval units in the area of the attack. Quickly the Naval Operations office gives orders for the rescue and the submarine hunt. The orders go to the code room, then Naval Communications dispatch them by radio or wire to the units involved; perhaps to a destroyer or other craft patrolling the coast, to a “mosquito” boat headquarters or a Coast Guard station from which a rescue cutter or flying boat can be dispatched to the scene, or to a lighter-than-air base, where blimps are ready to move out on a sub hunt. Seven hours after they took to the lifeboats the survivors are picked up by Coast Guardsmen - thanks to the ingenuity of the radio man and the vigilance of the communications watch on shore. Communications are the vital nerves of the Navy, and nothing is more secret. Even an admiral can’t enter the code room at Washington unless some important mission specifically requires it. Long before Pearl Harbor the pace of preparations for defense could be measured by the flood of messages handled in the Communications Office. From 1,534 messages a day in the early part of 1939 the average stepped up to 4,518 messages - 156,864 words a day - in July, 1941. Unquestionably the pace is even faster today. To relieve the load carried by radio, telephone and telegraph service has been expanded and telegraph printers brought into wider use. Before we entered the war the Navy operated 37 radio traffic stations, 28 aviation radio stations and numerous smaller radio stations assigned to particular activities. Establishment of the new hemisphere bases, new shore patrol stations and the world-wide operation of the Atlantic, Pacific and Asiatic fleets have made it essential to expand the communications facilities, and close cooperation with the Signal Corps of the U. S. Army has been effected through the Defense Communications Board, to which representatives of both branches of the service are appointed. Through the Communications center, the Operations Office must keep accurate check on the movements of Navy vessels - and presumably, too, of Allied merchant ships at sea. There may be hours or days of radio silence while warships convoy transports or supply ships across the ocean. Without a word to Washington that might betray its position to the enemy, a destroyer may swerve suddenly to blast with depth charges a U-boat lurking near the convoy’s path. Not until the ships are safe in port will the report on the submarine’s finish go over the air to some radio operator sitting at his typewriter in the Communications center. Or a long-range flying boat, which can talk more freely than a ship, may flash home the cheerfully laconic report, as did one recently: “Sighted Sub. Sank Same.” Communications between Washington and the ships at sea and the outlying bases are only a part of the picture. There is a vast amount of aerial traffic control handled by short waves, there is the detection of enemy radio messages and the monitoring of illegal transmitters - and there is the exchange of messages between ships by visual signals. Talking with flags is an ancient art, still practiced daily by warships, either with code flags flown from the mast or by wig-wag signals. When Prime Minister Churchill, returning to England on the battleship Prince of Wales after his visit at sea with President Roosevelt, passed a British convoy, his flagship ran up the three-flag signal “PYU,” International Code for “Good Voyage,” and, on the port side, spelled out “Churchill” in nine flags. Every ship in the convoy answered by flying the “V" flag. By night the blinker lamp replaces the flag - and woe to him that's slow on the draw. When blacked-out ships meet at sea there must be quick recognition or quick work at the turrets. Uncle Sam’s signalmen had better be quick, and they'd better be right the first time. The Navy would not like to blunder into a battle among its own ships, as the Italian fleet is believed to have done by mistaking signals after the Battle of Cape Matapan. The Communications personnel for the Navy was doubled from 1939 to 1941; in the latter year 1,350 officers, 9,200 radiomen and 3,150 signalmen were in service, and training has been increased at a rapid rate at the dozen or more special schools under the impulse of the war, which has expanded every branch of the service at an unprecedented rate. How much use if any is now being made of Frequency Modulation is a military secret, but it has certain definite advantages over the conventional Amplitude Modulation system. “FM” can operate on lower power, travels in a rather straight line with a known range, is static-free and is less likely to be picked up by enemy receivers. There have been published reports that German use of “FM” for messages on the eastern front gave them one advantage over the Russians, who had only conventional radios. Another communications method with which the U. S. Army is experimenting is writing “dot-dashes” on clouds with signal lamps. Every ship in the Fleet has its own intricate nerve system. From bridge to engine room runs one vital nerve, the electric bell signal to which the engineers must be alert at every instant. Telephones interconnect bridge and fire-control tower and turrets. And the old hollow tube that used to pipe the captain’s voice throughout the ship has been supplanted by the loudspeaker system that carries the “Call to Battle Stations” from bridge to lookout, turrets, magazine and galley. And it sounds pretty good, after a hot battle with a fleet of enemy bombers, to hear the booming voice of the “old man” come over the loudspeaker with a “Well done, men.”