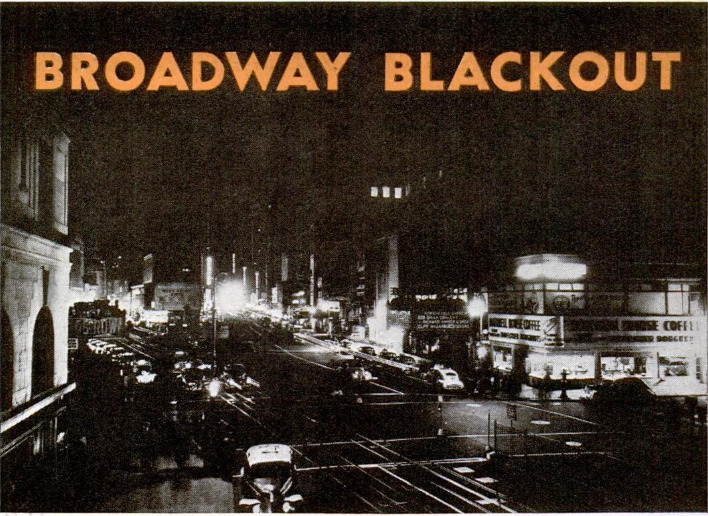

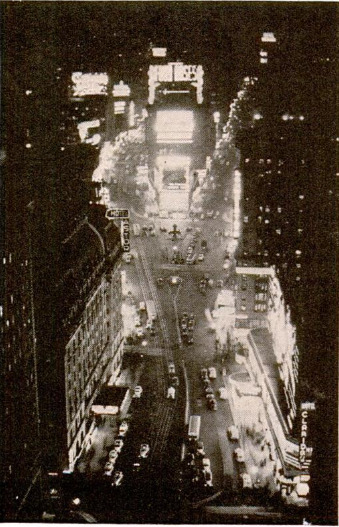

THE same scientific ingenuity that made the bright lights of Broadway one of the wonders of the world is being employed to, save these spectacular signs - now that the “dim-out” order of the army has extinguished most of the 200,000 bulbs which made the Gay White Way glisten. The result is that Broadway, already a canyon of unfamiliar, comparative blackness, may take on an eerie appearance like nothing ever before presented to the eyes of the estimated 1,100,000 nightly gazers who still visit the area. Some of the “spectaculars,” as the giant advertising signs are called, will soon blossom forth with gigantic fabric awnings and metal shields which permit the scintillating displays, but prevent the lights from striking clouds and setting up a glow which silhouettes United Nations’ ships, making them easy prey for Axis submarines lurking offshore. More bizarre are the experiments now being conducted by the leading sign corporations in the use of ultra-violet or “black light” to illuminate paints. If they succeed, the Gay White Way will no longer be white, but will glow with a ghostly luminescence - just as colorful, but no longer as glaring. Another line of research deals with the possibility of substituting motion for light, making the district a maze of mechanical devices - whirling windmills, waving arms, winking eyes, beckoning fingers, dancing feet. This would give the wartime spectaculars a daytime attention value even greater than they formerly enjoyed, although it is the practice of the sign companies to flash on the lights the moment daylight falls below normal. At night moving objects would heighten the queer effect of black light on Iuminous or fluorescent pigments. Another possibility under serious consideration is the strangest of all. Inquiry is being conducted on the value of taking the huge signs on tour of the United States just as Broadway shows go on tour to smaller cities. In this scheme, a giant sign would be routed to a city like Pittsburgh or Cleveland and erected there, remaining until most of the people in the vicinity had seen it. The high cost of Broadway spectaculars has been justified partly in the past by the fact that the street is a mecca for out-of-town visitors. It is possible that the lights which made New York City famous may go to the byways of the nation, instead of waiting for millions to come to Gotham to see them. Proponent of the “traveling spectacular” idea is Douglas Leigh, the sign wizard who owns most of the spectaculars on Broadway although he is only in his early thirties. His record for the unexpected makes the plan seem possible. So many novel features have been added to the signs along Broadway, particularly those erected by Leigh, that on a single stroll from Times Square to Columbus Circle, if the day happens to be murky so the lights can be lit effectively, one can get the time, the temperature, the weather prediction, hear the quarter hours sounded by radio chimes, watch an animated cartoon show, see famous Broadway characters in pantomime on a bank of lights, watch drinks poured by the use of flowing light, observe a coffee percolator steam, see great smoke rings puff from a soldier’s lips, and admire tall fountains of water shimmering and dancing behind the largest plastic screens ever constructed. The controls for some of these signs are as fascinating as the signs themselves. An example is the towering neon weather bureau atop a building at Columbus Circle. It is 4,000 square feet in size, contains 12,000 square feet of metal, 2,000 feet of a fluorescent neon many times brighter than ordinary neon, 1,050 electric bulbs, and 10 miles of wire. Four times a day, on a permanent neon landscape with a neutral sky above, it forecasts tomorrow’s weather. If the forecast is for rain, the word “rain” flashes on the sign while neon raindropsfall on the landscape. If the sun is going to shine, a big sun with sparkling rays appears. If it is going to be cloudy but warmer, clouds appear in addition to the sun. If it is going to be cold, neon icicles crystallize all over the sign. And if snow is predicted, beautiful giant snow crystals appear in white-and-blue neon. The whole mechanism of the sign is operated by remote control from the offices of Leigh where there is an instrument with a dial system, with 10 different weather conditions listed: warm, warmer, cold, colder, rain, fair, cloudy, snow, cool, cooler. Over a special telephone wire, Leigh, four times a day, telephones the New York Weather Bureau, to learn tomorrow’s weather forecast. Immediately upon learning, he turns the dial to the corresponding weather forecast, whereupon the proper word flashes on the sign and the proper scene on the landscape. A red light then flashes back in the Leigh offices, as a doublecheck against error. That's just so Leigh will know that when he is dialing “cold” or “snow,” the sign isn't dramatizing a heat wave. Another sensational sign is a three-paneled affair, with one panel on top and two underneath. On the top panel are eight plastic-enclosed fountains which spout water 20 feet high; centered between the fountains is a 35-foot, three-dimensional bottle. On one of the lower panels is a novel animated-cartoon mechanism. On the third panel is a bottle and glassy “pouring” effect in brilliant colored bulbs. The entire sign is 4,000 square feet in size, and includes, among other things 14,000 square feet of porcelain, 100 miles of wiring, 10,000 lamps, 4,104 photocells, and a total wattage of 200,000. This is the first time real fountains have ever been used in a sign on Broadway. They are enclosed in transparent tubes, so none of the watery spray falls on passers- by below. Colored lights play on the fountains which spout into a mushroom effect; when the watery mushrooms break up, myriads of multi-colored bubbles float in the transparent tubes. The tubes are made of plastic. Little air holes keep the tubes from frosting inside, and a mixture of anti-freeze keeps the water from freezing in the cold weather. There is an extra ring of water on top of each tube. This acts as a shower bath, rinsing the tubes inside and out, so they will always be clean. The pumps that spout the water are flexible, so that each one of the eight fountains rises to a different height, thereby making a variety of geometric patterns in the whole colorful spectacle. As the fountains spout the water, it drops into a metal container from which it is pumped up again. The same water is used over and over for 24 hours and then changed. The total amount of water pumped per minute is 2,000 gallons. The lights playing on the fountains are at their base: 56 flood lights in all. A drum of color, operated by a motor, passes over them giving a kaleidoscopic color effect. The lights are hidden by a real boxwood hedge, also making its first appearance on a Broadway sign. The animated-cartoon panel on this sign has a lamp bank of 4,104 lights on a screen 20 by 30 feet. The animated cartoons on this bank of lights, because of great improvements in the mechanism, are now more than ever like the Walt Disney cartoons, except that these, by the magic of photocells, are turned into electric lights. The 4,104 lights on the screen outside are controlled by a bank of 4,104 photocells in the control room behind the sign. The animated-cartoon films are projected by an operator onto the bank of photocells. The projector’s light beam can pass through only the transparent part of the film and not through the opaque part, so that if a negative film is used the picture appears in lights; and if a positive film is used, the background appears in lights and then the unlighted parts make the picture. The photocells that are touched by the light beam become activated, send the current to a bank of mercury tubes, which in turn magnify the current and turn on the corresponding lights on the screen outside. The animated-cartoon mechanism is much like television, but television operates by lines, while the Leigh cartoon signs operate by dots, or lights. To give you better figures, the picture on the electric screen outside on the sign is enlarged from a fraction of one square inch to a size totaling 93,744 square inches - in other words, more than 100,000 times. The first type of cartoon is one in which the characters are made in squares. A different drawing is made for each progressive movement, and a special non-shrinking paper is used. The drawings are then photographed, the trigger of a 16-mm. camera clicking each time a progressive movement is made. Then when the film passes the projector at 20-24 frames per second, the figures are in motion. These figures on the films are then projected onto the photocells. The second type of cartoon is made by using models for the drawings, then photographing the various drawings making the progressive movements. The third type of cartoon is the one in which 16-mm. movie shots are made of actual people. It is necessary, however, that the characters be photographed in front of a lighted screen. This gives sharp black and white definition. The blackout arrangement includes a half-block-long electric sign advertising cigarettes. The giant head (23 feet high) is of an American soldier in an overseas cap smoking a cigarette. By means of a patented device based on the principle by which you blow smoke rings, the soldier blows huge real smoke rings every five seconds into Times Square - a total of 8,500 smoke rings each night. The method of producing the right kind of smoke in the right quantity is a trade secret, but the method of causing steam to emit from a huge coffee percolator nearby is not. This steam is piped under the street from a plant many blocks away and it takes 50,000 pounds of steam a year to keep the sign operating. Meanwhile, there is always the chance that the submarine menace will be conquered, leaving only the danger of air raids and the need for sudden blackouts. If the signs flash on again, not one enemy bombing pilot will be able to use the canyon of color as a guide to strike at the heart of the nation’s largest city. The pressure of a finger on a single tiny switch, hidden in a towering bombproof skyscraper many blocks away from the twinkling river of illumination, will plunge into blackness most of the midtown spectaculars. The switch is smaller than the one which turns on the parlor light in most American homes. To make safety doubly certain, the blackout control set-up is duplicated right on Broadway in a small space near one of the most intriguing of the Gay White Way’s many signs. The sign, however, is so distracting that not one of the nightly gazers dreams that within a few feet of the spectacular an air raid watcher sits ready to click out most of the 200,000 incandescent bulbs and miles of vari-hued neon. Also concealed from the eyes of the million or more who nightly pack the glowing sidewalks of the theatrical district are a few more switches within an arm’s reach. These control the remainder of the greatest collection of advertising signs in the world. Soon the twisting of a radio dial is expected to be enough to eliminate the switches. In these days of clear skies, the magnificent show is seldom seen in its full glory and New York misses the spectacle. Still, while “Keep Them Burning on Broadway” is the slogan of the famous district, they don’t want them lit a second that would bring peril to the city or the ships at sea.

Popular Mechanics, vol. 78, n. 2, 1942

Popular Mechanics, vol. 78, n. 2, 1942