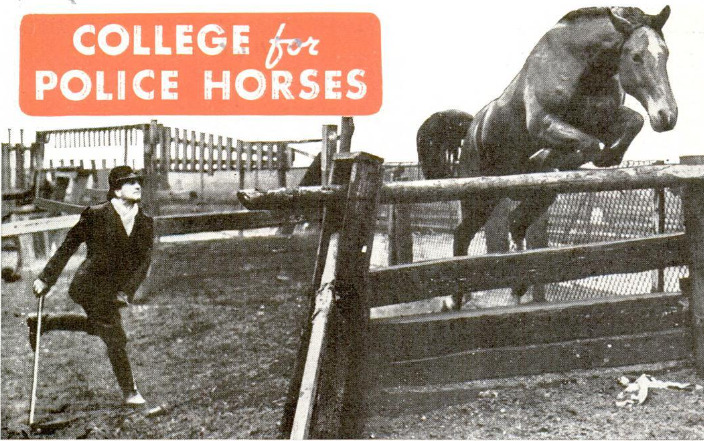

YOU might just call them police horses and let it go at that. On the department records they are “mounts” But members of the famed New York traffic squads speak of them affectionately as “pals” - these super-educated equines whose wise deportment on crowded streets never ceases to appear marvelous in a metropolis full of marvels. Faithful pals they have been in time of peace, thanks ‘to- their training in the unique police-training school. And faithful pals they will remain in time of war. The rigorous schooling they now undergo before facing the traffic maelstrom includes enough training in shrill and booming noise to withstand the scream of raid sirens and the crash of bombs. The only concession the New York mounted police have made to Nazi air blitz tactics is a strong but slender cord attached to each saddle. This can be used to tie a horse to a pole on a bombed street should the horse be left alone during an air raid while the officer is afoot on an emergency errand, the animal can be tied inside a building. But most of them won't need to be tied. It is this trick of standing quietly in the midst of a veritable river of honking and tooting traffic, or remaining motionless in a busy street after the uniformed rider has nonchalantly dropped the reins and strolled off, which puzzles hundreds of thousands of people. Anyone can make a horse stop and go. But how do you make one stand still if alone for fifteen or twenty minutes? What makes him remain patient and practically motionless in a dizzy traffic jam? Why does he wait there without being tied until his rider returns? The secret back of this phenomenon of horsedom reveals the intricate modern day psychology put into practice in New York City’s school for traffic horses. The horse is merely taught to relax. Day after day in a course of education that lasts from 12 to 16 weeks, a police horse is given a strenuous workout which includes galloping or trotting, jumping, wheeling, pivoting and climbing obstacles. The instructor watches shrewdly until the animal shows signs of fatigue. When the horse has reached the point where a rest would be welcome, the instructor halts the animal in his tracks with a sharp command, dismounts, drops the reins and walks off. Being fatigued and no longer having an instructor around to annoy him with more exercise, the horse does what most all tired little boys do when teacher leaves the room. He merely relaxes. Pretty soon he catches the idea that when a man gets off his back and walks away, one of his pleasant periods of relaxation has arrived. He just unwinds his nerves and stays there thinking his equine thoughts. This moment belongs to him. Why work when there is no work to do? Anyway, he learns to stay put. The analogy between the schoolboy and the police horse is closer than one might believe, and Sergeant Jame. Gannon, who is in charge of the school that has been turning out crack police horses for a quarter of a century, uses something like schoolboy psychology. Take, for instance, the manner in which a police mount will stand in the middle of a teeming street with automobiles whizzing past in two directions at a dangerous rate, some missing him by inches. If he shied from one, he would jump in- to the path of another. Now for a schoolboy parallel. Children are not taught to fight school fires, or avoid school fires, or jump out of school windows in time of fire. They are taught to drill - all about fire drill and nothing about school fires. They get so accustomed to thinking about the drill that the idea of fire never crosses their minds. The fire doesn’t exist as anything of importance. Thus they have no fear and are docile in an emergency. Likewise, for a well trained police horse, automobiles do not matter as far as he is concerned. From the beginning of his training he is permitted to nose around them. Usually there is an instructor near. The horse is brought to such a stage of alertness to the wishes of the men who work and coax and discipline and pet and feed him that it has no time for interest in an automobile, whether it is moving or standing still. To complete the explanation of this traffic training, the instructors delve into the realm of telepathy or mental suggestion. “It seems to be a fact,” says horse-wise Sergeant Gannon, “that these animals communicate with each other through some unspoken language. We know that because we use a trained horse to teach a green one. “But stranger still, it appears that a horse can to some degree read the mind, or the emotions, or at least the intentions of his rider. How much of this is mental and how much physical reaction it is hard to tell, but the point is that when our instructors are breaking in a horse, they just never give a thought to an automobile when they are around one. Neither does the horse. “On the other hand, a sudden start of the rider will bring a horse to immediate attention and he glances about to see what has disturbed his master. They seem even to respond to the moods of the policemen in time of excitement or peril, but it is hard to tell how much of this response is due to the tightening of a knee, or the slight motion of the hand holding the rein.” Whatever the reason, it is an axiom of the department that a cool policeman usually has a spirited, but tractable and dependable mount. This relationship between horse and rider may explain another remarkable trick practiced by New York police horses - swinging their shoulders carefully into a crowd to break up an illegal gathering without trampling citizens. When a mounted patrolman approaches a gathering of citizens, he does so calmly and without either fear or anger toward the crowd. He gives his horse the same slight nudge of the heel and the same easy pressure on the reins which the instructors taught the animal to obey in school and the result is not a lunge or leap, but a series of dainty, five-inch sidesteps before which the crowd falls back. The danger of a horse lashing out into the crowd with his hoofs is unheard of. After his friendly but firm schooling, a police horse will permit a friendly man to lean an elbow on his rump and smoke a cigarette. He learns to trust a man behind his back. The pressure of the foot toward the direction in which the instructor wishes the animal to sidestep is more than a signal. As the rider presses one foot into the animal’s ribs, it throws him slightly off balance in the intended direction. The rider’s other foot is moved out and this further shifts the horse’s center of balance. A slight movement of the reins tells the horse it is time to move sideways to restore his balance. As the horse learns, the pressure becomes more and more slight. This is true of all motions of a mounted man. The horse gets acquainted with his master and soon learns that a mere hunching of the rider’s body forward means that he is to move ahead. Pretty soon the horse responds almost as if he were a part of the man’s body - moving in the proper direction almost as soon as his master has made up his mind and telegraphed his wishes by some imperceptible movement. Or perhaps by telepathy, as some horse-lovers think. Each of the 400-odd mounted police horses now active in the city was a problem in himself when he went to “college” in the big town corral in the Long Island City section. Some are docile; some are too spirited; some are a bit clumsy or dull; others are sly, and it is the job of the instructors to mold them into a common pattern of dependability. Occasionally, a fine police horse will develop a case of nerves and “go haywire" - a sort of a shell-shock victim in the battle for traffic safety. The cure is a curious one. He is taken to the training stables and merely left alone for a while - left alone in the sense that the men have as little to do with him as possible for a period of weeks. His food is changed and enriched.He is permitted to fatten up. Once a day, perhaps, he is turned out to exercise at random. He is allowed to mingle with other horses occasionally, perhaps to exchange horse gossip. The rest of the time he is left in his stall to meditate on his troubles or worries, whatever they were, that caused him to shy at autos, jump around in the street, or disobey orders. At any rate, a period of fattening and relaxeddiscipline usually gets him ready for reentering and soon he is learning his lessons all over again. About half of the horses ridden by the men commanded by Captain James Meehan of the Mounted Division are bought in New York and half in Chicago. The eastern horses are more docile and more alert than the westerners, which are rugged, suspicious and doubtful about mankind, his intentions and his teachings. The easterners are neater in appearance and the westerners are a bit shaggy of coat and heftier in build. All are geldings. The horses must be either a true bay, or in the family of bays which is a mixture of red and brown. They must weigh around 1,100 to 1,200 pounds and stand about 16 hands high. They must be not more than eight years old and not less than four and be of the saddle type. Most of them have thoroughbred blood somewhere in their veins and some are former race horses, particularly jumpers. They cost an average of $300 and put in an average of 15 or 16 years in service. No matter where they hail from, whether farm, ranch or race track, they seem to know that man is their master and they recognize the whip as his badge of authority, along with the rein, the voice and the gentle pressure of a foot or leg. Police department horse experts claim they can pick an intelligent and eventually docile type by actions and appearance. Their results seem to prove them right and the whip as a weapon is not part of the equipment in New York City’s school any more than it’s standard equipment in police tack. The whip wielded by the instructors is a thin leather thong six to eight feet long on a five-foot handle and by its very unwieldy proportions is of little value for punishment. It is a symbol of authority, however, and the horses respect it. As soon as they get wise to the ways of their teachers the animals perform their tricks as a proud privilege. They build a new and responsible world of duty around themselves and are cager to do their share of police work - as might be expected of policemen'spals.