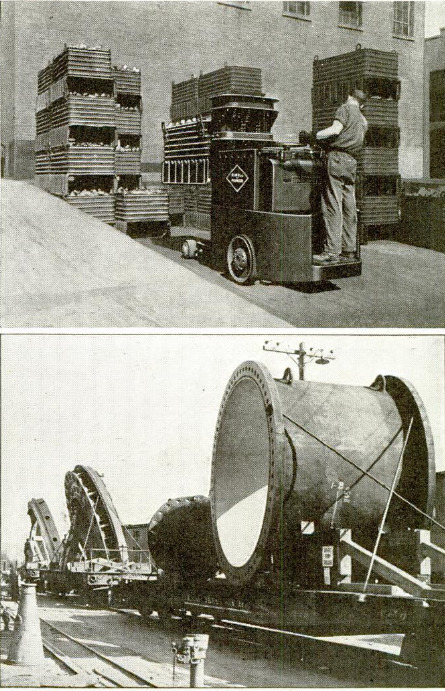

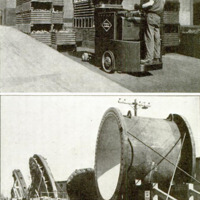

WAR BEGAN trying to break the back of the railroads three years ago, and it’s still trying. The freight load on American rails rose 55 percent from May to October, 1939. For many months they have delivered every day more than 5,000 car-loads of war materials to government camps and construction projects. That's 50 miles of freight cars a day. Now that we're in it, the burden grows enormously. Tankers go down in the Atlantic, the east cries for oil, and the railroads step up tank car deliveries tenfold, from 1,827 cars in one January week to 19,926 cars in an April week - an all-time record of 640,478 barrels per day. The Panama Canal is virtually closed to intercoastal shipping and the rails take over the job, which may give full-time employment to as many as 35000 freight cars. Tires are rationed and folks and goods that went by highway go by train. The stuff they carry is as strange as it is stupendous. Special 24-wheel flatcars cradle a big coast-defense gun. Towering turbine parts ride from eastern factories to western dams. A Denver shipyard builds a vessel for the navy and sends it west by rail. Prefabricated sections of steamers’ hulls are loaded at inland plants. Last year the railroads did the biggest job in history. This year should be 10 percent bigger. Carloadings are expected to hit a million a week. Last October’s peak was 922,000 cars. And yet the railroads are doing this - hauling nearly 25 percent more tons of freight per mile than in 1918 - with 625,000 fewer freight cars and 21,000 fewer locomotives than they owned in that other world war. How do they do it? There are a number of answers. “Big Boy” is a typical one. “Big Boy" - there are 20 of him on the Union Pacific line - is a Hercules among locomotives, capable of hauling more than a mile-long freight train more than a mile a minute. Just under 133 feet long, it is the biggest steam freighter in the world, so long that it had to be hinged at the center to take the curves and grades over the Wasatch mountains between Ogden, Utah and Green River, Wyo., where it does the work of two ordinary engines. Of the 4-8-8-4 type, “Big Boy” has16drive wheels, weighs 1,197,800 pounds and pulls the biggest freight you ever saw at 80 miles an hour top speed, “cruising” at 70. The railroads may have only two-thirds as many locomotives as they had in ’18, but they do more work. The average steam engine of 1918 had a tractive effort of 34,995 pounds; today’s average engine is rated at 51,915 pounds. “Big Boy’s” rating is 135375 pounds tractive effort, and it has an expected working life of 3,000,000 miles. Another new powerhouse on wheels is the Chesapeake & Ohio railway’s “Allegheny” type, with a 2-6-6-6 wheel arrangement never before used. There are 10 of these $250,000 locomotives, and more ordered, built to haul coal across the Allegheny mountains. Another big lift for the general power average of 1942 lomomotives is provided by the growing fleet of main-line Diesel-electric freighters with their tremendous tractive effort of 220,000 pounds. All these modern giants are equipped with roller bearings that let them ride with the friction-less ease of a ship in water. A handful of men can push a million-pound locomotive with roller bearings. So - “more power to the railroads” is one answer to the question, “How do they do it?” Other answers are - better equipment, better track. Grades and curves have been ironed out, heavier rails installed so that streamliners and freights alike go faster. Twenty years ago less than 1.5 percent of the steel rails weighed 110 pounds or more per yard; today 22 percent. Freight car hot boxes then were five times as frequent as now, locomotives broke down seven times as often. The creaking, groaning, swaying boxcar has been to the rejuvenation clinic. It's built now of lightweight steel, some with wrought steel wheels good for as many as 300,000 miles; and the average freight car carries nearly nine tons more than in 1918. The roads will add about 115,000 new freight cars and 1,000 locomotives in the year ending Oct. 1 if materials can be obtained. They're shooting at a fleet of 1,765,000 cars and over 42,000 engines on that date. Since 1923 they've junked 40,700 old locomotives as obsolete! Fast? The average speed of all freights between terminals - including stops - in 1921 was 115 miles an hour; now it’s 16.7 miles an hour, 45 percent faster. Furthermore, they burn less fuel doing it. Twenty years back it took 162 pounds of coal to pull 1,000 tons of freight one mile; today it takes but 111 pounds of coal. The railroads measure transportation in tons carried per mile. Here’s where the contrast between 1918 and 1941 shows up in black and white. In the first half of 41 the ton-miles per freight car were 57 percent greater than in '18. In other words, today’s car is delivering three-fifths more transportation. Diesel-electric switchers shunt carloads of TNT and high-explosive shells up and down 100 miles of track at one of the government’s big new ordnance plants, and these isn’t a semaphore in sight. Inside the cab of one of these locomotives the engineer is listening to his radio. “Pick up 5 carloads of TNT at track 7, deliver to magazine 47, track 4,” comes an order; and a minute later, “Ten carloads of shells half a mile ahead. Proceed slowly.” A dispatcher controls all the deadly traffic in this vast yard by two-way FM radio. This is a private, “intra-mural” railway, of course, but it’s typical of the new techniques the roads are adopting. Short-wave radio signals, for example, direct traffic in one big freight classification “hump” yard. Another system now in operation on many railroads, doubling the capacity of their tracks, is the two-way, reverse traffic signal. It enables the operation of trains in either direction on both tracks. To cite one example, one midwestern railroad is installing two-way signals on a section of its double-track main line, thus converting several miles into the equivalent of a four-track line. The westbound freight that used to pull over into a siding and wait while the streamliner streaked by westward can now roll right along while the fast passenger train highballs past on what normally would be the eastbound track. All the trains on the division will operate without written orders, governed by the wayside signals controlled by dispatchers watching their movements on illuminated “Centralized Traffic Control” boards. Signals on the section of two-way operation read in both directions. Waybills sent by teletype, messages sent by facsimile and carrier currents step up the pace of both freight and communications. Electric “mules” snake around loading yards hurrying the freight aboard. Tough little electric high-lift trucks pick up huge loads and trundle ’em into box-cars. One of these baby giants can lift a 10,000-pound loaded steel container and set it in its proper place on a compartment freight car. It takes all kinds of freight cars to move the load. There are more than 100 types of tank cars specially designed for milk or molasses, oil or acid, water, ice cream. Hopper cars with watertight hatches protect cement and similar perishables from rain. End-loading boxcars accommodate army tanks, trucks, bomber wings. Port- able refrigerators on wheels, loaded into ordinary boxcars, obviate the use of a full-size refrigerator car for small lots of frozen foods and flowers and fish. Underslung flatcars take on half-million-pound ingots and ingot molds for armor plate. Pneumatic dump cars automatically tilt to either side to dump 50-yard loads of earth. In peace time the 235,000 miles of American railways carry about two-thirds of the nation’s freight. In war the burden is heavier; more than any other war in history, this is a war of movement. The army has told the railroads they must be ready this year to assign 2,000 cars a day for ordnance shipments. Every five seconds a freight train starts its run. Every five seconds a passenger train slides out of its terminal. The railway system, says the War Department, is “the backbone” of national defense. The main line is the front line today.

Popular Mechanics, vol. 78, n. 2, 1942

Popular Mechanics, vol. 78, n. 2, 1942