-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

A Pigmy Zeppelin

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

A Pigmy Zeppelin

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

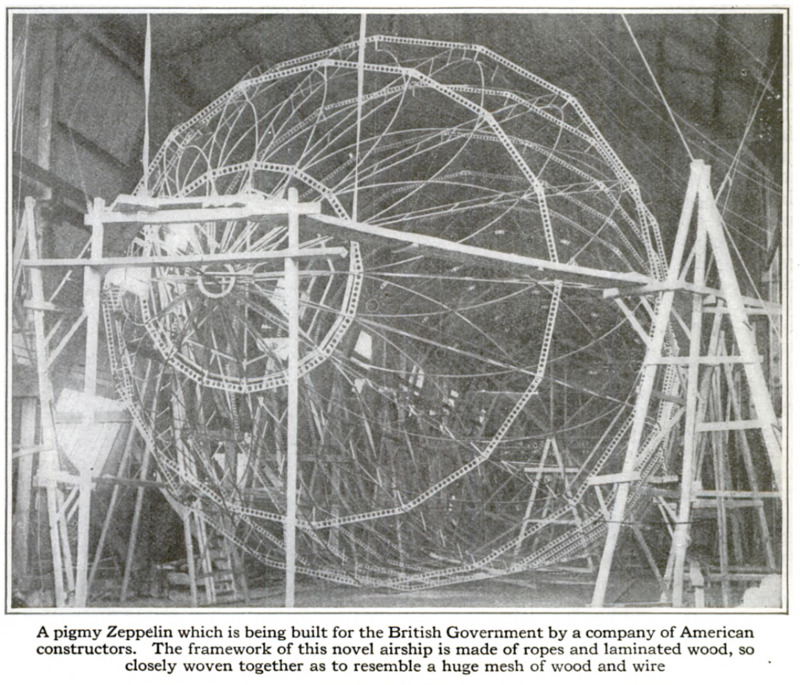

A PIGMY Zeppelin (pigmy as Zep-

pelins go) with a basket-work

frame of layered wood has been

recently built for the British Govern-

ment by a number of American con-

structors, including T. Rutherford Mac-

Mechen, president of the Aeronautical

Society of America, and Walter Kamp,

a prominent American aeronautical de-

signer.

One of the chief efforts of the designer

has been to reduce the weight of the hull

and car without sacrificing strength, and

this has been accomplished, he believes,

by the substitution of laminated wood

for the aluminum which composes the

framework of the Zeppelin. The rings

which are used to keep the hull in cylin-

drical form are made of thirty-nine thin

layers of mahogany, carefully glued to-

gether, and covered by a steel collar.

Thirty-two wooden ropes, hardly as

thick as a man’s thumb, wind again and

again around the hull, weaving the whole

into a great mesh of basket-work. = Six-

teen slender members form the longi-

tudinals, running from how to stern, and

intersecting the spirals of wooden rope

where they cross each other. The func-

tion of the spirals and longitudinals

acting together is to distribute the gas

lift and strains evenly to all points of the

hull.

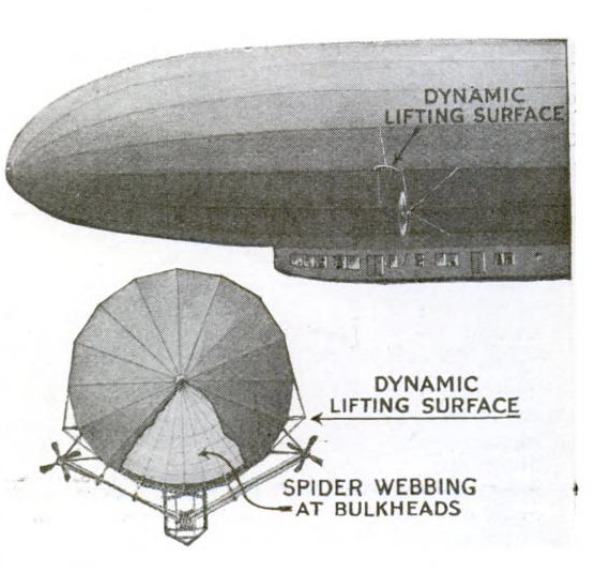

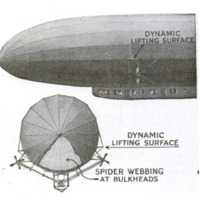

There are, in reality, two hulls, the

inner enclosing thirteen balloonets or

gas bags and the outer supporting a

waterproof and airtight envelope or

skin. Twenty-nine ribs, or transverse

girders, encircle the inner hull, and a

spider web of wire cables stiffens the

alternate ribs and forms the bulkheads

between the balloonets.

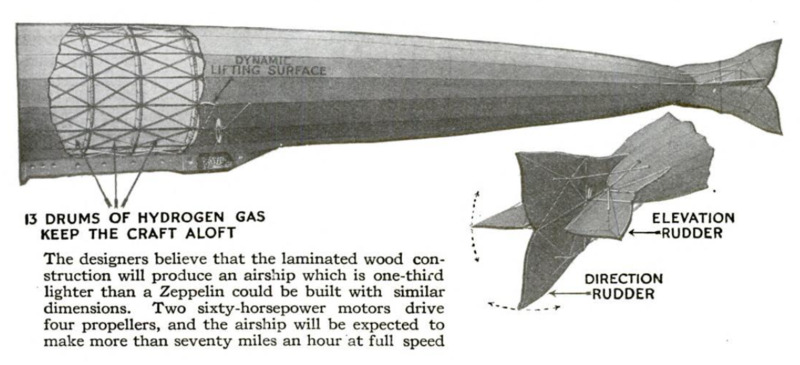

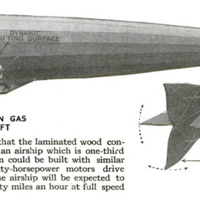

Two cight-cylinder, sixty-horsepower

motors have been installed, and by

means of cable drives transmit the power

to four propellers mounted high above

the car, two being placed on each side of

the slender torpedo-like hull.

In hot weather, or when the airship

passes through a heated stratum of air,

the gas expands, exerting more lifting

power, and causing the airship to rise.

To control this tendency, the gas has to

be artificially cooled, or it will be neces-

sary to release some of the valuable

hydrogen to allow the ship to retake its

proper altitude. On the contrary, if a

sudden wave of cold air strikes the gas

bag, the gas immediately contracts, and

part of its lifting power is lost. If there

is no means for heating the gas and ex-

panding it, ballast will have to be

dropped from the car, thus compensating

the decreased lifting power of the gas

by a lighter weight which it has to

carry.

The control of the lifting power of the

gas in the MacMechen dirigible is in

the heating and cooling process. To

keep the hydrogen from cooling and

losing its lifting power, hot vapor from

the engine is blown into the foot-wide

space between the balloonets and the

outer skin of airtight cloth. To cool and

condense the gas for descent, or to pre-

vent its expansion to an extent that

causes an undue inflation of the gas bags,

cold air is introduced into the same space

by means of a luminum disks with re-

volving shutters at the bow and stern.

It is claimed that by this method of

will make about seventy miles an hour,

or about ten miles an hour faster than

the speed of a Zeppelin.

The Porurar Scinxci: MONTHLY be-

lieves that this airship will prove disap-

pointing to its builders and to the

British Government. Previous experi-

ments with wooden frames in dirigibles

have proved costly failures. The Zep-

pelin’s first rival, the Schiitte-Lanz

dirigible, was built with wooden frame-

work, and proved much heavier than a

Zeppelin of the same dimensions. Lami-

nated wood was used in the experiment

and this was found faulty and discarded.

The Zeppelin of to-day is the product of

practical experience, as is the second,

and successful, Schiltte-Lanz, which

discarded the weblike wooden frame for

the lighter metal ribs and strakes of the

Zeppelin. Such a solid frame as that of

the pigmy airship would not do for a

larger dirigible, for it loses the greater

lightness for the same strength of a

small structure. In a small dirigible

resistance against propulsion is so much

greater than the \ift available for engine

power in the large craft, that it com- |

pletely discounts the small craft's struc-

tural advantages. Any improvements in

lightness and strength will, therefore,

never make this pigmy Zeppelin a

superior in speed to its larger and more

powerful rival.

The whole idea of a small and speedy

“aerial destroyer” is mistaken, since in a

dirigible everything has to take second

place to speed; otherwise Zeppelin,

which cannot seek safety in landing,

would be at the mercy of the wind.

The rope drive to the propellers has

been proved greatly inferior to bevel

gearing, chains and belts. The cable

drive was tested on the first Gross-

Basenach, but was quickly discarded.

The most meritorious feature of the

design of the pigmy Zeppelin is in the

alternate heating and cooling of the gases

by hot vapor from the engine and cool

air sucked in by blowers. This certainly

should prove of valuable assistance to

the dynamic lift-control without en-

tailing much additional weight.

In conclusion, it seems that the idea

of a wooden frame has been tried, ap-

proximately in its present form, and

found lacking. The rope drive has been

succeeded by more efficient means of

power transmission, and the entire trend

of dirigible construction has been to in-

crease the lifting power, and consequent-

ly the size, in order to achieve greater

power and speed. Whether the Zeppelin

has been a success or not is a mooted

point, but the Zeppelin has been the

only 'dirigible that has accomplished

anything of note in this war, and the

smaller dirigibles have been permarently

relegated to their hangars.

A Barbed-Wire-Proof Fabric

ONE of the most trying tasks incident

to trench fighting has been consid-

crably lightened by the appearance in

the British trenches of gloves made of a

fabric which is said to be impervious to

barbed-wire points. The fabric is made

up into mittens, with the first finger and

thumb separate. The fabric is water-

proof, and in addition the gloves are

insulated for gripping electrically-

charged wires.

The same material is applied to the

manufacture of ~sleeping-bags, which,

when opened, may be thrown over a

barbed-wire entanglement to allow a

soldier to climb over the sharp points

without injury. When made up into

vests or tunics, the fabric is strong

enough to turn shrapnel splinters, or

even a bullet when it has lost part of its

momentum. The interlining is anti-

septicized, so that if a bullet goes

through, it takes into the wound enough

antiseptic wool to prevent poisoning.

The materials used in the manufacture

of this remarkable fabric have been

sedulously kept secret this far.

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1916-04

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

483-485

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Filippo Valle

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 88, n. 4, 1916

Popular Science Monthly, v. 88, n. 4, 1916