-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Undersea Fighting of the Future. II.-Battling with Telephones

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Undersea Fighting of the Future. II.-Battling with Telephones

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

IF the war has taught us anything it

has taught us that the submarine

must be reckoned with both as an |

annihilator of battleships and as a de-

stroyer of commerce. Of the dozens of |

instrumentalities

invented for killing on

a wholesale scale it is

the most terrible. And

yet how crude is_this

new weapon! Com-

pared with what it can

be made it is what the

blunderbuss of old is

to the modern rifle.

Consider for a mo-

ment how a submarine

boat is handled. The

commander plows

along at the surface

much as he would on

any ship. In the offing

he” sees a pillar of

smoke. Friend or foe?

He: must investigate.

Changing his course,

he steers for that

cloud on the horizon. In fifteen minutes

he has approached near enough to dis-

cover that the smoke is pouring from the

funnels of a hostile collier. She flies the

naval ensign of her country, and she is

convoyed by a torpedo-boat destroyer.

Thesubmarine commander givesan order.

Water surges into tanks in the subma-

rine’s hold. The craft sinks until only

her periscope projects from the water.

Heading for the collier the submarine

arrives within half a mile of its prey.

The commander takes the bearings of

the collier by compass and orders com-

plete submergence. In another minute

the craft is completely under the surface.

A sharp command, and a puff of com-

pressed air starts a torpedo from one

of the launching-tubes. In less than

a minute it has reached the collier. There

is a dull explosion. Fifteen minutes later

a cargo of four thousand tons of coal lies

at the bottom of the sea. and a hundred

brave men have per-

ished miserably.

Why the Submarine

Is Crude

It seems very simple,

very certain, this tor-

pedoing of a ship from

a safe place under the

water. But for all that

it is unscientific and

haphazard. The sub-

marinecommander sees

nothing below the sur-

face ; that is why he

must take aim before he

submerges. To strike,

the target must be large

and very near ; other-

wise he would surely

miss. Suppose that you

were told to shoot

blindfolded at a mark one hundred yards

away and that you were given two

minutes to locate the target before your

eyes were covered. You would be exactly

in the position of a submarine com-

mander about to torpedo a hostile

ship. Is it any wonder that torpedoes

must be fired at close range? Is it not

obvious that the submarine could be

made still more terrible if the submarine

commander could locate his quarry

accurately in the inky blackness in

which he is immersed?

To use lights under water is hopeless.

Even millions of candlepower would not

reveal the presence of a ship a mile off

to a submerged underwater craft. But

suppose that the commander of a sub-

marine could locate his prey by sound;

suppose that he could hear a ship and

locate her by sound more accurately, for

example, than a blind man can locate the

position of a ticking clock in a room?

Might not that solve the problem?

With this thought in mind, I have

worked out a method of utilizing micro-

phones—a method which is a modifica-

tion and extension of that which I

described in the POPULAR SCIENCE

MonTHLY for October, 1915. Those

who read that article will remember

that I showed how it was possible to

make a torpedo guide itself toward the

beating propellers of a ship with the aid

of microphones—*electrical ears,” as T

call them. A microphone is found in

every telephone transmitter. It is an

instrument for intensifying feeble sounds,

or for transmitting sounds, and it is

based on the principle that the transi-

tion between loosely joined electric con-

ductors decreases in proportion as they

are pressed together. The conductors

form part of a circuit through which a

current is passing, and the variations in

pressure due to sound waves in the

vicinity of the conductors produce

variations of resistance, and hence

fluctuations of the current, so that the

sounds are reproduced in a telephone

receiver. Inthe modern telephone the

transmitter is essentially a microphone,

the pressure of the sound waves being

communicated to the conductors by

means of a diaphragm.

In a torpedo of the type I described in

the POPULAR SCIENCE MONTHLY, the

microphones are mounted in pairs on

both sides of the nose. So long as the

sound of the hostile ship's beating pro-

pellers, traveling through water far more

readily than sounds travel through. air,

affect’ all microphones with equal

intensity, the torpedo rushes on straight

to its mark. But if the vessel should

change its course, the vibrations of the

propellers would no longer strike the

two pairs of microphones with equal

force; one pair would be more affected

than the other—the pair directly ex-

posed to the vibrations. At once

electrical circuits are closed and auto-

matic mechanism started which swings

the rudders of the torpedo and points

the nose of the torpedo toward its mark.

As soon as the microphones on both sides

are restored to electrical equilibrium, in

other words as soon as they hear with

equal clearness, the torpedo keeps on a

straightaway course.

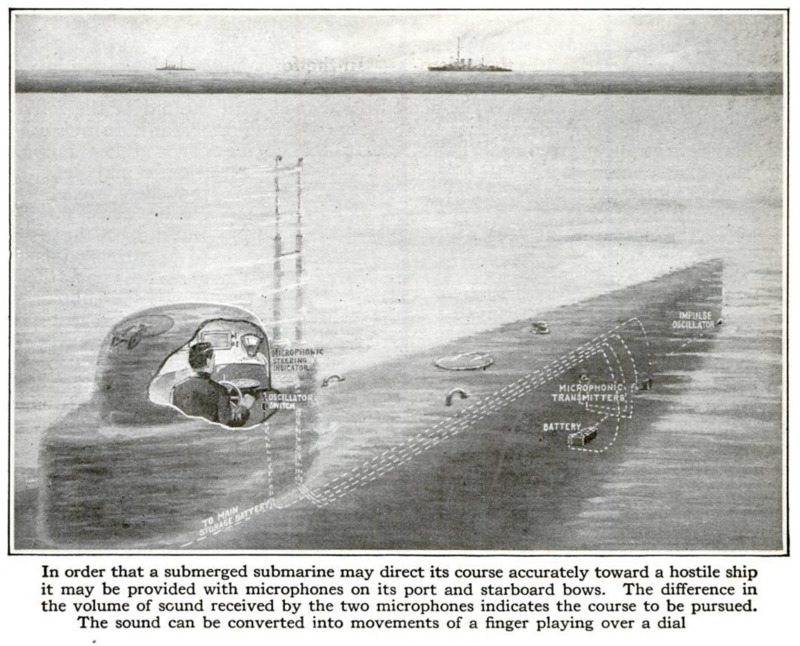

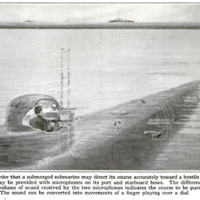

It is evident that the same principle

can be applied to submarine boats travel-

ing under water, with the difference that

since the submarine is manned by intel-

ligent human beings, the microphones

can be made merely to indicate the

course to be pursued, leaving to the

commander the task of steering a true

course. As in the case of the sound-

controlled torpedo, the submarine is

provided with microphones on its port

and starboard bows. Telephone ear-

pieces are provided which enable the sub-

marine commander to listen to the

sounds gathered by the microphones.

If the submarine is not pointed head on

toward the ship to be destroyed the

microphone on the off side will hear less

than the other, and the difference in the

volume of sound received by the two

microphone detectors will be noted at

once in the telephone receivers. The

commander changes his course until he

hears equally well with both ear-pieces.

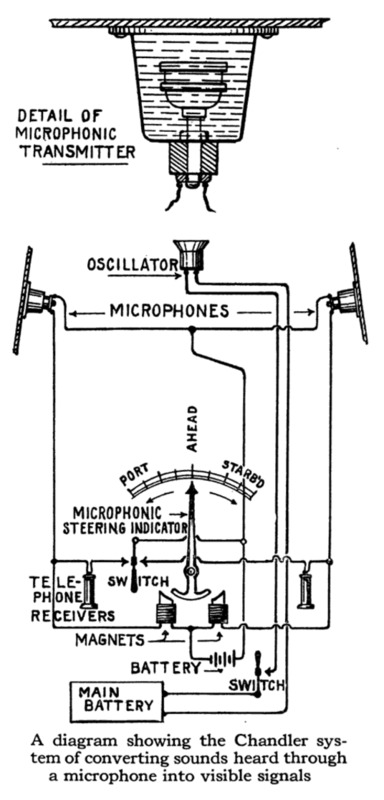

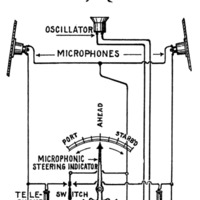

Seeing Sounds on a Dial

While it is perfectly feasible to direct

a submarine by telephone it is much

more effective to convert the microphone

vibrations into visual signals. As a

result the commander of a submarine

has only to watch a finger move over a

dial in order to know what course he

should steer. In a sense he sees the

sound which the microphone detectors

hear. The accompanying diagram sets

forth the essential principles of this

conversion of the microphone vibrations

into visual signals so clearly that an

extended description seems hardly neces-

sary.

While a visual steering indicator is

primarily depended upon to guide the

submarine on its deadly errand, tele-

phones are connected with the micro-

phones, to be used when the occasion

arises. With their aid the commander

learns a new language. He realizes the

meaning of strange grindings, hums,

moans, blows, mur-

murs and vibrations

—the many tongues

of the sea. If we but

knew it the water of

the ocean is a veri-

table Babel; it is a

great reservoir of

sound, the recipient

of ten thousand differ-

ent vibrations, rang-

ing from the grinding

of pebbles to the

pounding of steam-

ship engines. Justasa

woodsman learns the

meaning of the weird

soughing of wind in

tree tops, the “woof”

of a bear, the patter

of deer’s feet and the

cll of quail, so a

submarine comman-

der can distinguish

one underwater sound

from another and in-

terpret it correctly.

A tramp steamer can

be microphonically

distinguished from a

Mauretania, a tor-

pedo-boat from a

superdreadnought,

and above all a sub-

surface craft from a

surface craft. Thus

the character of an

unseen ship miles away can be ascer-

tained.

But apart from listening to passing

ships, che telephones will be required to

receive messages from an admiral on a

battleship five miles away. Both war-

ships and merchantmen are equipped

with submarine signaling devices —

devices which send forth either bell

sounds or rhythmic vibrations. It is

easy to see how useful they can be made

to telegraph orders to a submarine under

water five miles or more away.

Under Water Echoes and How They

Are Applied

In the foregoing account of my inven-

tion I have assumed that the vessel to

be attacked with the aid of the micro-

phonic steering-indicator is in motion— |

that its engines are giving audible

sounds and that its

propellers are churn-

ing up water noisily.

But suppose the vessel

to be attacked is at

anchor—what then?

Is not the submarine

commander helpless?

The difficulty is

easily overcome if we

can make the sub-

marine produce a

characteristic sound

and if we can have

that sound echoed

back from the ship to

be sunk and picked

up by the submarine's

own microphones.

Fortunately Professor

Fessenden has pro-

vided an instrument

ideally suited for the

purpose. Called an

oscillator, it may be

regarded as a kind of

underwater klaxon

horn, the diaphragm

of which is electrically

vibrated to emit a

characteristic bleat.

By means of a switch,

located near the hand

of the submarine com-

mander, the oscillator

can be turned on or

off.

~ Theoscillator will be of use not only to

locate a ship at rest but to save the

submarine in a nerve-racking emergency.

Imagine the commander of a U-boat

bent on the destruction of a ship enter-

ing a harbor and traveling along at the

surface with only his periscope exposed.

A fast armed motorboat looms up—a

type of craft which has proved to be

a most formidable enemy. The sub-

‘marine must act quickly. There is but

one course—to sink quickly. Valves are

opened and tanks filled. The craft

sinks out of sight. It is safe for the

moment. The agonizing uncertainty of

the crew can be imagined. They know

that a relentless enemy awaits them, that

his searchlights sweep the water all

night. Hour after hour drifts by. If

the submarine’s commander rises, a hail

of shot and shell is sure to rain upon

him; if he stays under water very long

he and his men will die of suffocation.

Why not move on? The waiting motor-

boat cannot see him. But in what

direction and how far? He is almost

sure to run into the shore and to puncture

the thin shell that saves him from

inundation. If he could only locate the

harbor entrance he would be safe. An

oscillator and a set of microphones will

enable him to head for the inlet as surely

as if he were traveling on the surface

and he could see it with his eyes. He

pulls the switch of the oscillator. A

shrill note is sent through the water.

His eyes on the steering indicator dial,

he watches the response of the finger

to an echo. The echo of what? Of the

oscillator’s vibrations reflected by the

shore. He steers this way, now that way,

barely crawling along, always watching

for the echo on the dial. The finger on

the steering indicator moves from side

to side as the microphones pick up the

echoes. At last there comes a moment

when the finger stays at zero, when, in

other words, there is no echo for the

microphones to hear. That

can mean only one thing: the

oscillator is sending out its

bleat not toward an echoing

shore, but toward the har-

bor's mouth and toward the

open sea, where safety lies.

PE and on the verog

indicator the commander sig

nals “full speed ahead,” know-

ing that salvation lies before

him.

Artificial Senses Take the

Place of Eyes and Ears

The use of microphones on

submarines not only increases

the effectiveness of the sub-

‘marine enormously, but opens

up new and intensely dramat-

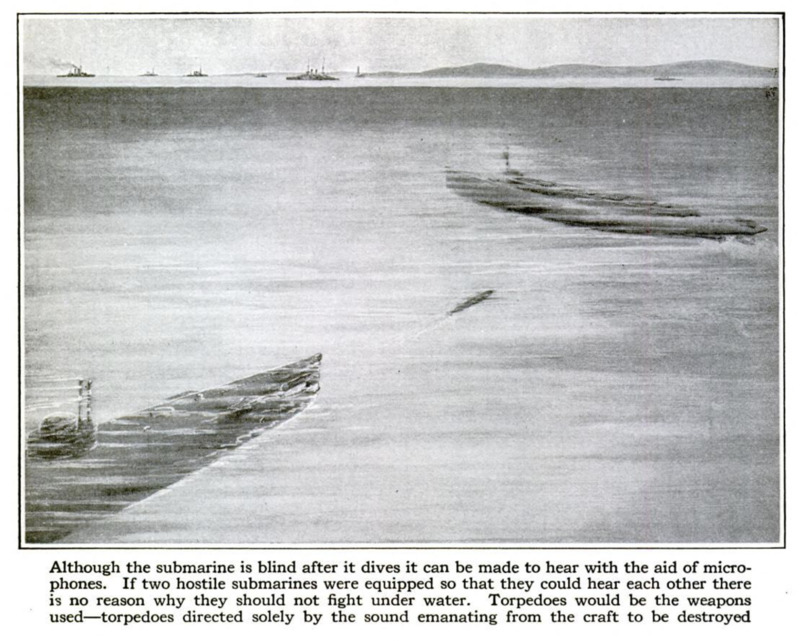

ic possibilities. As soon as

one submarine is equipped

with devices for threading a course

underwater with certainty all submarines

will be similarly equipped. Grant that

and at once we have the means of

pitting submarine against submarine, of

actually engaging in submarine fights.

‘What strange encounters they will be—

these underwater engagements of the

future! Two vessels, blind but for

steering indicators connected with micro-

phones, circling around each other in the

effort to ram or to plant a torpedo at the

right moment, cocking electrical ears, as

it were, and mancuvering entirely by

sound—what battle of Wells or of

Verne's can compare with it? Instru-

ments, artificial senses, take the place

of Nature's eyes and ears; hidden move-

ments are electrically translated into

twitches of a quivering finger on a

graduated dial; one intelligence is pitted

against another. Surely this is real

scientific warfare—this battle of micro-

phones!

A Sewer Banquet at $25 a Plate

TC celebrate the completion of a new

sewer in St. Louis a cabaret banquet

was held in the tube. A “banquet room"

three hundred feet long and a gas-

equipped kitchen were created. The

food was cooked in the tunnel and served

on_ twelve tables placed lengthwise.

The cost of the banquet was twenty-

five dollars a plate.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Edward F. Chandler (inventor and writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1916-06

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

805-809

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Filippo Valle

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 88, n. 6, 1916

Popular Science Monthly, v. 88, n. 6, 1916