Protecting a Battleship with a Belt of Air

Item

-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Protecting a Battleship with a Belt of Air

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Protecting a Battleship with a Belt of Air

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

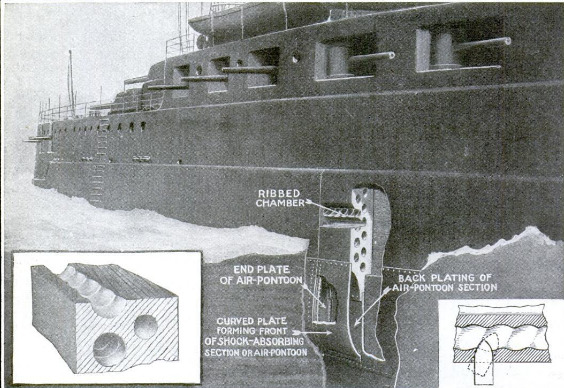

READ the accounts of the battles

fought off Heligoland and the

Falkland Islands, in which ships

protected by heavy side armor were sunk

by gun fire at ranges of five miles and the

question must occur: What is the good

of armor? If twelve and more inches of

steel can be penetrated by the fifteen-

inch guns of a British battle-cruiser at

distances of miles it would seem as if

victory in sea engagements is a matter of

hitting power rather than of protection.

That armor of some kind is necessary

would follow from the fact that naval

architects are very close students of

naval history and that they promptly

apply in the construction of fighting

ships the lessons taught on the proving-

grounds and in battle. That the heavy

gun seems for the time being to have

gained the ascendency over armor is

proved by the fact that in battle-cruisers

high speed and enormous striking power

are considered more important than

steel sides; for the armor belt of a

battle-cruiser is only twelve inches—

hardly sufficient protection against any-

thing but projectiles of low caliber and

low striking energy.

Inspired by these considerations, Louis

Gathmann, whose experiments in hurling

high explosives against armor on proving-

grounds attracted much attention some

sixteen years ago, has invented an en-

tirely new system of armor protection

which deserves consideration. His ob-

ject is to obtain not only protection, but

lightness; for the heavier the armor of a

ship the fewer must her guns be or the

weaker her engines on a given displace-

ment.

In carrying out his ideas Mr. Gath-

mann would provide a ship with a cham-

bered shell-resisting. section and with a

shock-absorbing section, the first above

the second, as the accompanying illus-

tration shows. The chambers of the

first or shell-resisting section are really

horizontal tubes, the front series of

which are spirally ribbed. ‘Should a

projectile penetrate the hard face of the

armor,” says Mr. Gathmann, “it would

force its way

through the line of

least resistance,

and thereby glance

upward, down-

ward or sideward

as the case may

be, turning or

tilting the projec-

tile, thereby

destroying its

penetrating power;

such shells may

fracture or explode,

but without pene-

trating the armor.”

A fifteen-inch

shell carrying high

explosive generates

gases on exploding

which exert tre-

mendous pressure. That pressure must

be absorbed, or else it may breach

the ship below the armor belt. So,

Mr. Gathmann attaches to the lower

edge of his chambered belt a series of air

chambers or pontoons, each independent

of the other.

Study the illustration which accom-

panies this article and you will see that

this shock-absorbing section consists of

five walls: a downwardly-extending

portion of the armor belt; a rear plate

to which that downwardly-extending

portion is bolted; a curved front plate,

and two end plates to enclose the

pontoon or chamber.

The pontoons seem flimsy, and in

reality they are. But they are intended

to be destroyed. The pressure of the

gases from a huge shell will disrupt one,

two, perhaps three shock-absorbing or

pontoon sections, but the rest will re-

main intact. The air within the cham-

ber will have a cushioning effect. Water

will rush into the compartment, but the

pantoons will still remain in place.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Louis Gathmann (inventor)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1916-07

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

18-19

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Filippo Valle

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 89, n. 1, 1916

Popular Science Monthly, v. 89, n. 1, 1916