-

Titolo

-

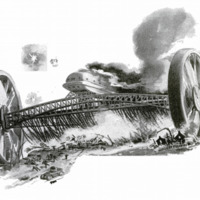

Giant destroyer

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

The Giant Destroyer of the Future

-

extracted text

-

CLUB, a bow and arrow, a blunderbuss, an infantryman'’s rifle, a forty-two centimeter howitzer are merely instruments for delivering blows. The essential difference between the battles of prehistoric times and those of today lies in the manner of delivering blows. Smokeless powder has merely lengthened the arm of a modern fighter. He strikes and kills at a distance of miles.

For all our machine-guns, for all our terrible “artillery preparation,” battles are still won by bayonets. Tactics have been somewhat modified since Napoleon's day, because of the invention of the machine-gun and the high-powered field-piece. But the individual fighter is still as important as he ever was. We speak of the German or French or Russian “war machine,” when we mean a million or more individuals trained to act with a precision that roughly approximates that of a modern university football team.

Only the Battleship Is a Real War Machine

Because armies are still composed essentially of many individuals, fighting ships may be more fittingly termed “war machines.” A modern battleship is a real machine. The men on board are merely somany intelligences that control the steam-engines, the turrets, the great guns, the searchlights. No one ever hears now of hand to hand conflicts at sea. Ships are sunk at ranges of five and seven miles. But land warfare is still waged not by a few machines, as on the sea, but by organized millions of men.

Armies have increased in size. Fighting ships, on the other hand, have diminished in number. Contrast the numerical strength of the British Navy now with what it was in the days of Drake and Nelson. A few dozen ships, highly intricate machines, have taken the place of hundreds.

Why is there no land battleship, something comparable with our own Pennsylvania, something which will concentrate within one volume the striking power of an army?

Why Not a Battleship On Land?

There is no good engineering reason why an enormous wheeled structure, heavily armored and capable of traveling at high speed should not wage the battles of the future. Technically, it is a far easier task to design and build a super-dreadnought than a wheeled destroyer to run on solid ground. The ocean is a vast, level expanse. There are no hills and valleys. Water is the same in density everywhere. But land varies from the hardest rock to the softest quagmire. Here we have the reason why we still oppose armies against each other instead of machines.

Undeniable as these difficulties are, it seems to me that they could be overcome by boldly designing a machine of such dimensions and of such energy that it could travel over ordinary land much as an automobile travels over a country road. A hill fifty feet high would be to that machine what a six-inch ridge of clay would be to an automobile; a swamp would no more hinder its course than half a foot of mud would stop a touring car. Its speed would be at least one hundred miles an hour on the long, level, sandy beaches along our coasts. And even over rough infand country it would rush far more swiftly than any touring car on a poor road. Indeed, in its speed would lie its destructive possibilities. The impact of a heavy mass moving with the velocity of an express train would be irresistible. It could mow down everything before it with the relentlessness of a steam-roller. Guns would not be required to rout an enemy. An army would be as helpless in offering resistance as a flock of geese in the path of an automobile.

A Giant Three-Wheeled Armored Car

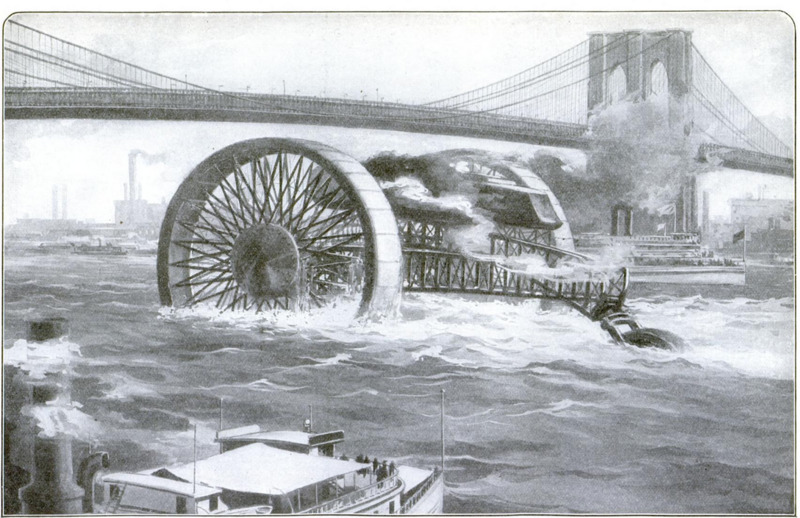

It is impossible within the limits of a short article to describe this machine which I have conceived in all its details. Picture to yourself, however, a self-propelled machine, comprising three wheels and a heavily armored body or car. There are two wheels, one hundred and fifty to two hundred feet in diameter in front, and a single smaller steering-wheel in the rear. The entire structure is short, so that the turning radius will be small.

No doubt you are familiar with the military masts of our American battleships. They are latticed towers, not unlike cages. They are thus constructed so that whole sections of the lattice work may be shot away; but the remaining portions will still support the mast.

So I would build the wheels of my war machine. Why not armor them instead? They would weigh far too much—thousands of tons in fact. But the hub I would armor—and heavily. There the spokes would be concentrated so thickly that they might be shot away in great numbers. Besides, the hub and axle must be well protected. Therefore the center of each wheel would be a mass of armor as thick as that of a battle cruiser.

The two front wheels of this war machine would have to be spaced about three hundred feet apart. They would have a tread about twenty feet wide,—in other words, about as wide as an ordinary room. I would make them of steel plates four inches thick, bolted together in sections.

Since the machine is to destroy by virtue of its inherent energy and not by means of guns, it would have a comparatively small car—a car which would not rise above the tops of the front wheels, which would be heavily armored, and which would serve primarily as a housing for the engines. The crew would be small—not more than perhaps thirty men.

I am fully aware that the problem of obtaining engines which will give this war machine a speed of one hundred miles an hour is not easily solved. But if thousands of horsepower can be developed by the engines of pitching and rolling battleships it is not unreasonable to suppose that competent engineers can be found to design and build steam engines of twenty thousand horsepower, fed by oil-fired boilers.

Once more let me state that the front wheels are one hundred and fifty to two hundred feet in diameter. Hence, they would make less than fifteen turns to the mile.

How Shocks Would Be Absorbed

That simplifies the matter of absorbing shocks. If a racing automobile on a fine track leaps into the air when it strikes even a pebble, simply because the spring suspension has not time to respond to the shock, it is obvious that the huge structure that I have in mind must be provided with inordinately strong yet sufficiently sensitive shock-absorbers. The shock that would be experienced in knocking down a small factory building, would certainly not be as great as the shock that must be absorbed asa modern fifteen-inch naval gun suddenly recoils after discharge. If cylinders filled with oil can check the terrific recoil of a big gun, they can also act as shock-absorbers on a land war machine. And so they can be imagined on the machine—huge cylinders, three feet in diameter, filled with oil which would resist the pressure of pistons on the axle.

The weight of the entire structure would be probably five thousand tons. Since the machine is to batter down everything in its path, there are to be suspended from the front of the machine a series of heavy weights, each weighing several tons. The weights may be raised or lowered. When dropped into position their impact at high speed would level everything before them.

Only Big Guns Could Stop the Machine

Terrible as this contrivance would be, it would not be able to withstand bombardment by 16-inch Skoda or Krupp guns. It is not intended for that. Ordinary field artillery will not stop it. Its sole purpose is to move up and down an enemy's country, to make a whole region untenable, to crush down resistance offered by ordinary field fortifications. Mines will be planted to blow up the destroyer. Mines do not prevent a battleship from venturing upon the sea. Moreover, the maneuvering power of the land war machine will be such that it may change its course wilfully with such rapidity that a whole countryside would have to be blown up in order to affect it.

Imagine yourself standing at one front wheel of this machine. Comparatively you would be no bigger than a baby standing beside the driving wheel of a passenger locomotive. Far above you would be the maze of spokes constituting the latticed wheel. Perched midway between the two gigantic front wheels, as tall as many a moderate sized office building, would be the ship-shaped armored car for the engines and the crew. You reach it by means of an elevator resembling that in which miners rise from deep coal mines. Once in the car, you might fancy yourself in the engine room of a ship; there is no difference so far as general appearances go. With the commander you step into the conning-tower—a circular, armored chamber well forward, dominating the entire landscape.

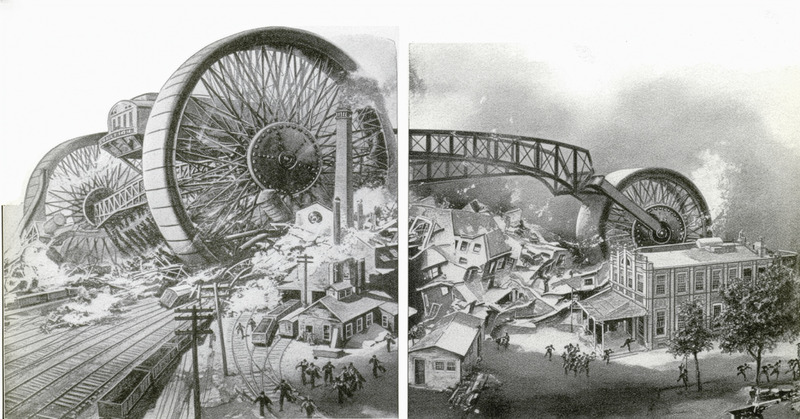

The commander gives a signal. The machine moves. It gains headway. Soon it travels at express-train speed. A mile ahead is a densely wooded park. In a minute the machine reaches it. Does it stop or swerve? It plunges on. Trees are crunched as if they are mere weeds. You look back in the wake of the machine. It is as if a storm had laid low every poplar and elm. And yet the machine is not even scratched. An enemy village, occupied by enemy soldiers lies in front. The machine speeds on toward it. It reaches them. Houses are battered down as if they were made of paper. Wherever the weights that dangle down in front strike, wherever the wheels move, there is a rending and a crushing. And so, everything is leveled before the war machine—walls of earth or masonry, houses big and little, railway stations and signal bridges.

-

Autore secondario

-

Frank Shuman (inventor and writer)

-

Edwin F. Bayha (illustrator)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1916-12

-

pagine

-

897-901

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Filippo Valle

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)