-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

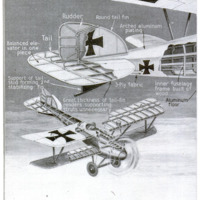

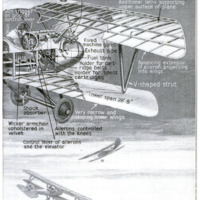

German Albatross Destroyer

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Like a Wasp on the Wing

-

Caption 1: Upside Down in Mid-Air. We used to marvel at the men who looped-the-loop in flying machines or slid down sideways or tail first, wondering what was the good of it all. The wildest acrobatic feats performed at flying-machine meetings before the war are now part and parcel of every fighter's tactical equipment. He must put himself in a favorable position and if necessary must loop-the-loop to do so.

-

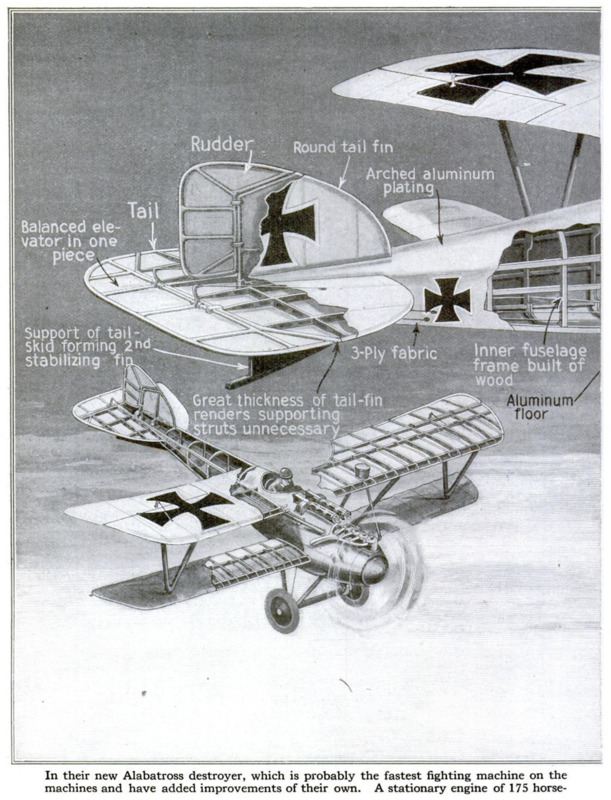

Caption 2: In their new Alabatross destroyer, which is probably the fastest fighting machine on the western front, the Germans have copied the best features of the French and British fighting machines and have added improvements of their own. A stationary engine of 175 horse-power drives the Albatross through the air at the tremendous speed of over 130 miles an hour

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

THE war will be won by |

that power which |

launches into the air

the greatest number

of the fastest fighting

airplanes. This seems

to have been realized

from the day when it

dawned on the general

staffs of Europe that

artillery must be aim-

ed by a man several

thousand feet in the

air, that the enemy

must be prevented

from similarly direct-

ing his own fire, and

that as a result, fight-

ing machines must be

resorted to in order

to gain supremacy in

the air. As a result,

the warring nations

have been trying to

outstrip one another

in producing the fast-

est and most formida-

ble fighters. British,

French, Germans

have all commanded the air at different

times, and the times usually coincided

with the appearance of faster and more

improved machines.

‘Whenever the newest type of hostile

machine is captured, it is examined with

microscopic minuteness. The curve of

its wings, the spacing of its struts, the

shape of its fins and tail, the material of

which it is made, the proportioning of its

different parts—everything is measured,

tested and noted. It is not only studied;

it is copied. This is no time for riding

pet hobbies. The best that the enemy has

must be not only imitated, but bettered.

It seems to be conceded in the British

and French despatches that the new

German Albatross destroyer known as

“type D-III” is for the time being the

fastest and most formidable fighting

airplane on the Western front. In this re-

markable piece of mechan-

ism we see embodied in

steel, wood and linen, all the

lessons so bloodily

driven home by two

years of fighting in the

air. The new Alba-

tross is an amalgama-

tion of the best fea-

tures to be found in

the original small Al-

batross and the latest

fast French Nieuport.

Above all things, a

fighting machine must

be fast. A speed of

one hundred and thir-

ty miles an hour is

about the minimum

now. In addition to

speed, the machine

must have the maneu-

vering power of a

wasp; it must be

able to dart up and

down and in and out

with the rapidity of

an insect.

In the French Nieu-

port machine these two essential qualities

of speed and maneuvering ability were

more highly developed than in any other.

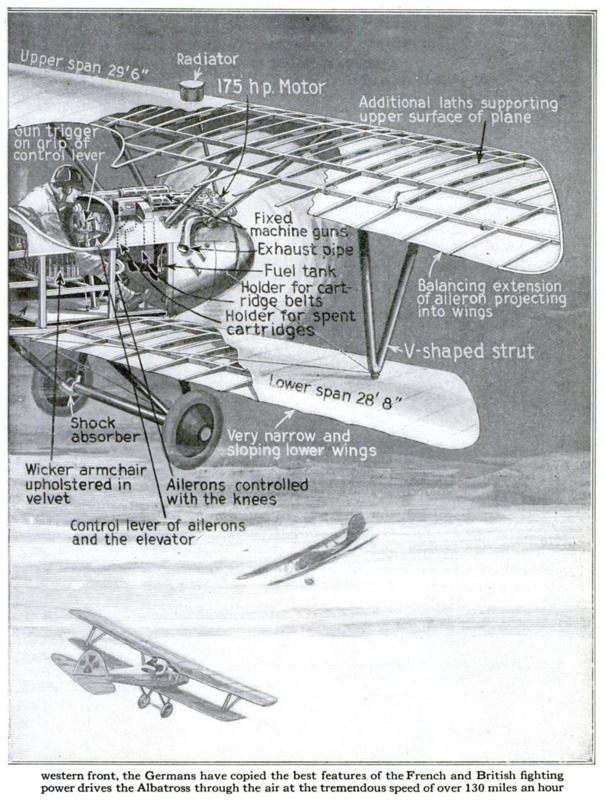

The Nieuport is a biplane in which the

lower wing is but half as wide as the

upper. We look at the Albatross. Sure

enough, its lower wing is one-half the

width of the upper. In the fast Nieuport,

the wings are “staggered”—that is, the

lower wing lies not directly below the

upper, but slightly to the rear, so that the

front edge of the lower wing is just be-

neath the rear edge of the upper one.

Why is this done? Because the struts

that tie the two wings together can be

shortened. Shortened struts, in turn,

mean less wind resistance. Look at the

detail drawing of the Albatross that ac-

companies this article. You see at once

that the Albatross, too, has “staggered”

wings and short struts.

‘Why is the lower wing narrower than

the upper? There is a kind of interference

between upper and lower wings. The air

is ‘“‘caught,” as it were, between the

superposed surfaces. 1f the lower wing is

narrowed this interference is largely pre-

vented. But there are structural reasons,

too, for narrowing the width of the lower

plane. Note in the drawing that the

struts are triangular in form and that the

rear member of a triangle lies directly

behind the front member. Isn't it obvious

that the triangular strut thus formed is

strong and light and that it will offer less

resistance to the wind than if a rectangle

with diagonal wire bracing were adopted?

Note, too, that the staggered wing con-

struction with the narrow lower plane

makes it possible to fasten each triangular

strut directly to the lower main beam.

This adds to the strength of the entire biplane.

But the Germans have improved upon

the Nieuport in this: They have spread

the central struts which hold the upper

wing to the fuselage or body, far apart.

Hence the two wings are tied together by

only two sets of struts—the triangular

ones previously described and the central

ones. Why was this done? Simply to

avoid the use of wires. In the older ma-

chines, by which I mean machines that

flew in the early weeks of the war, there

were a far greater number of wires than

would now be considered permissible.

Wire bracing extended in all directions.

Now, a piano wire which vibrates a

distance of half an inch to either side of

its normal position offers as much re-

sistance as a rod one inch in diameter. A

wire may seem thin, but when it vibrates

it is the equivalent of a thick rod. It

offers much resistance as a result. And

s0 we find the airplane designers of the

world trying to get rid of wires. The

builders of the Albatross have gone far

in this direction.

From the British, the Germans copied

the rounded outline of the tail fins. The

tail surfaces of a flying machine have

much the same effect as the feathers of an

arrow. They steady the machine. The

perfect target arrow has rounded feathers.

This explains the British tail formation

of the German Albatross.

More than any other fighting machine

thus far designed the Albatross is shorn

of projections. Indeed, the craft ap-

proaches a bird in cleanness of line. The

water tank, for instance, is no longer

found near the engine; it is built into the

upper wing. The radiators, through

which the cooling water circulates, lie

flat against the fuselage or body.

Steadying fins and rudders and ailerons

(the hinged surfaces at the rear corners of

the upper wing, serving to balance the

machine from side to side) must be strong

and stiff and yet free from external sup-

port. But their wind resistance must be

low. The Germans met the situation

by giving the fins and rudders a stream-

line form, which means a shape that parts

the air most easily. The steadying effect

of a fin depends in part on its area.

Additional area was gained very cheaply

by filling out the space between the fuse-

lage or body and the tail-skid.

The fuselage or body in which the single

fighter sits is noticeably large. But mark

the lines. This smooth, correctly de-

signed bulk, large as it is, parts the

air with the lowest possible resistance.

Note how the fuselage and the wings

are tied together so as to get rid

of struts and wires. The idea is not new,

but it has been so ingeniously carried out

that it deserves mention here.

The exhaust from the engine is care-

fully collected and conducted downward

and rearward. Whiffs of exhaust gas

should not be added to the tribulations

the pilot already has to bear.

It takes a certain amount of muscular

effort to swing a rudder quickly. Clearly,

the fighter who can swing his rudder most

quickly has the greatest maneuvering

ability. The muscular effort involved,

must not retard a man from making the

right turn at the right moment. Hence

we find that in the Albatross all the con-

trolled surfaces are balanced, which means

that triangular extensions are provided

beyond their pivots. You will find this

clearly brought out in the tail of the

Albatross as it is shown in the accompany- *

ing drawing.

Since the entire machine must be swung

around in order to aim a gun, it is obvious

that as many as twelve guns could be

mounted if there were place for them.

Indeed, on the Nieuport as many as five

have been carried—three on the upper

‘wing and two firing through the propeller.

No doubt a similar practice is followed

by the Germans. In our drawing we have

shown only two machine guns firing

through the propeller.

How astonishing it is to find the in-

ventions of fairy-tale writers brought to

realization. For years we have been en-

tertaining our children with one of the

most beautiful fairy-tales of Hans Chris-

tian Anderson—a tale in which a wicked

prince rashly essays to fight God himself

with ships flying through the air and

mounting guns that rain thousands of

bullets in response to the mere pressing

of a button. Look at the Albatross and

you will see the magical buttons attached

to the control-lever. Who knows but

flying machine designers may find other

improvements suggested in what we have

been pleased to consider the poetic

vaporings of romancers!

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Carl Dienstbach (writer)

-

Underwood and Underwood (photo)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1918-01

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

55-58

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

References (Dublin Core)

-

Europe

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Filippo Valle

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 92, n. 1, 1918

Popular Science Monthly, v. 92, n. 1, 1918