-

Titolo

-

Aerial reconnaissance

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

The eyes in the air. All aboard for a reconnaissance flight over the German lines

-

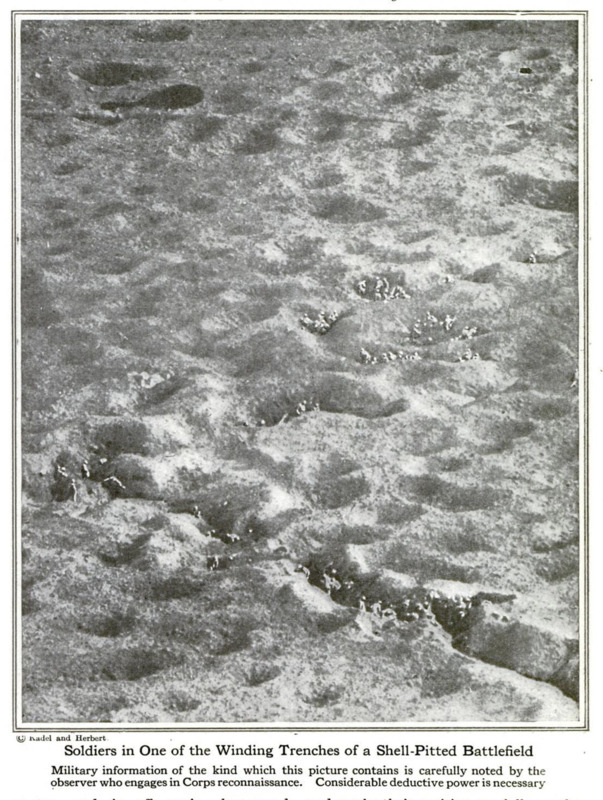

Caption 1: Soldiers in one of the winding trenches of a shell-pitted battlefield. Military information of the kind which this picture contains is carefully noted by the observer who engages in Corps reconnaissance. Considerable deductive power is necessary

-

Caption 2: Army reconnaissance observers study enemy airdromes, make a note of the number of hangars and planes on the ground and watch the movements in towns and large encampment

-

extracted text

-

IN the British Flying Corps there are

two kinds of air reconnaissance work—

Corps and Army. Corps reconnais-

sance is carried out by a single airplane

and army reconnaissance by squadrons of

machines numbering not less than five

and as many as thirty. To understand

just what a Corps reconnaissance flight

means it will be necessary for me to trans-

port you to an active section of the West-

tern battlefront during the summer.

A two-gun, two-seater Sopwith fighter

is trundled out of a hangar. While the

pilot is inspecting the map of the territory

over which he is to fly,

the observer receives

his orders to get infor-

mation on the move-

ment of enemy troops,

motor transports, trains

and the direction in

which they are going,

over an area of not

more than ten thousand

yards in front of the

allied position. A du-

plicate of the pilot's

map and writing ma-

terials are ready in the observer's seat.

As the final order is given, the plane

ascends and wings its way over the lines

towards the enemy. The pilot climbs

rapidly, keeping a wary eye open forenemy

air-raiding squadrons. The usual height

at which he operates is from six thousand

to ten thousand feet.

Nearing the German lines the observer

eagerly scans the ground below through

powerful glasses. If you were to look

through these same glasses you would see

mile after mile of shell-marked earth—

every mile seemingly the same as the

next. But to the observer every foot of

that ground holds information worth

noting, information which he is willing to

givehis life to get. The pilot doesn’t linger

over the battlelines. His work is still to

be done back of the enemy’s trenches.

Far below the plane is a thin wisp of

white smoke. To the uninitiated it

means nothing; but the men in the plane

know that it is a train winding towards

the front. Its position is quickly marked

on the map.

What's That Cloud of Dust?

A white road next occupies their atten-

tion. The pilot drops the plane a little

-utterly oblivious to the anti-aircraft

shells bursting around him. One part of

the road is obscured by a black smudge

and a cloud of dust. A regiment of in-

fantry is on the march. Why infantry

and not cavalry? The dust cloud tells.

It would hang in the |

rear of cavalry and the

men and horses would

look like black specks. |

It is such deductive |

reasoning as this that

an observer has to be

trained to make: |

The observer esti-

mates the number of |

troops by figuring what

space they occupy. A |

little further on, three

black specks move rap- |

idly down the road. Motor trucks in a

hurry. All this is recorded by the watch- |

ful observer who becomes more keen as

the minutes pass.

The plane is over a railroad station now.

Are there any parked motors? How many

cars are on ithe rails? Several work- |

ing parties below run for cover when the

plane hovers over them. Evidently this

is an important depot as seven ‘“‘archies”

hurl shells skyward in an effort to scare

the aerial visitor away. A shell bursts |

near by. The plane rocks from the ex-

plosion. Then, as the pilot shuts off the

motor, the machine dashes earthwardina

nosedive. No! he is not hit. The ob-

server just wants a closer view of the |

depot. Nearer and nearer the plane |

swoops, with machine-guns from the

ground adding to the din from the anti-

aircraft guns. Five hundred feet from

his objective he flattens out, opens up the

motor, and is off again—homeward

bound.

Again the battlelines come into view

below, and the observer looks out for new

trenches. Sure enough he sees several,

and marks their position carefully on the

map; also whether they are traverse or

communication trenches. The condition

of the barbed wire entanglements next

engages his attention. Where they are,

broken by shell fire he sees smudges and

spots, all of which are faithfully recorded.

Camouflage or a Battery—Which?

The shells come thick and fast, but the

pilot is an old hand at the game; he'll

stick till the work is done. Cleverly

hidden on the ground, the observer sees

some small narrow-gage tracks, terminat-

ing in several pits. Has he discovered a

new enemy battery, or is it camouflage?

He must see the gun flashes before being

sure. There they are! One! Two!

Three! Four! Five! He also sees the

blast marks in front of the battery. Now

he is satisfied. Signalling the pilot he

focusses his glasses again—this time in the

direction of home.

A few minutes later, watchers at the

R. F. C. airdrome see the reconnaissance

plane winging its way back home, and

shortly it settles safely to earth outside

the hangar.

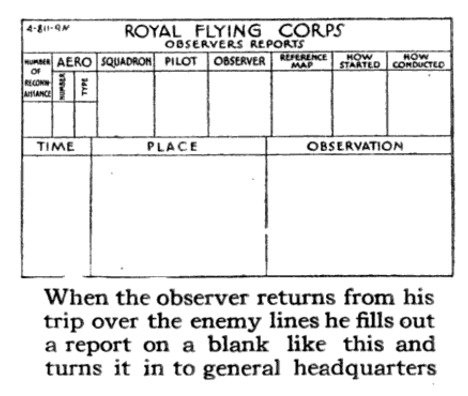

The observer fills out his report on a

blank similar to the specimen shown

on page 508 and turns it in to G. H. Q.

(General Headquarters). The filing of

this report marks the conclusion of the

Corps reconnaissance.

Army reconnaissance squadrons carry

cameras and take photographs at many

different points. One of these squadrons

will often fly several hundred miles into

' enemy territory in order to gain desired in-

formation. Instead of writing down single

items as in Corps work, the observers

report the general impression gained from

the entire trip. The reason for this is

that there are sure to be many movements

which are not important, when a large

territory is covered. Army reconnais-

sance observers study enemy airdromes,

make a note of the number of hangars and

planes on the ground and watch the move-

ments in towns and large encampments.

Rivers and canals are also looked for,

particularly if there are any ships on them.

The size and type of boat must be re-

ported; also to which side it is nearer.

What the Observer Looks For in

Army Reconnaissance

The railroads, highways, woods and

towns are studied as in Corps reconnais-

sance, except that an especial look-out is

kept for hostile kite-balloons, “blimps,”

and aircraft. Each squadron is escorted

by scout machines whose duty it is to keep

off attacking planes. The pilot of an

Army reconnaissance plane must not

give offensive battle to the enemy. The

scouts are there for that. Should an

enemy plane get through the formation,

however, it is the observer's duty to see

the enemy first and open fire. If he

doesn’t it probably means that his plane

will “crash,” and not only will he and his

mate go down to death, but the records

for which they risked so much will be

destroyed.

Army reconnaissances are carried out

at from one to twelve thousand feet, and

strict orders are issued that there be no

straggling. A favorite pastime of the

Germans is to send three or more ma-

chines into the air to look for our strag-

glers. Perched high in the sky, generally |

about eighteen thousand feet, these |

hawks watch and wait. Suppose a fight-

ing scout has motor trouble or wants to

look around a little. He swings out of

line and the others close in. Soon the

squadron is almost out of sight, home-

ward bound with the precious reports.

The scout flies along at about fourteen

thousand feet. Then down from their

perch swoop the Germans. The rat-tat-

tat of their machine-guns warns the allied

pilot of his peril. He may down one or

possibly two of his antagonists, but in the

end he crashes to earth the loser in an un-

equal fight. That is why R. F. C. orders

read “Do not straggle; to do so means

the loss of pilot and plane.”

In Corps reconnaissance the pilot does

not run such a risk, as he flies over a com-

paratively small territory and can gen-

erally dash for home if attacked. Of

course he has to contend with anti-air-

craft shells and the possibility of a sur-

prise attack from the air; but for all that |

his lot is easier than that of other pilots

who venture far into enemy territory.

You will be astonished to learn that the |

average age of R. F. C. pilots doing |

reconnaissance work is twenty and of

observers twenty-two. It requires young.

blood and muscle to stand the strain, risk

and excitement of this branch of the air |

service. That results so far have more |

than justified expectations, is a tribute to |

the skill and bravery of these youngsters.

-

Autore secondario

-

Henry Bruno (writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1918-04

-

pagine

-

508-511

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Filippo Valle

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)