-

Titolo

-

Why Tanks Are Giant Caterpillars

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

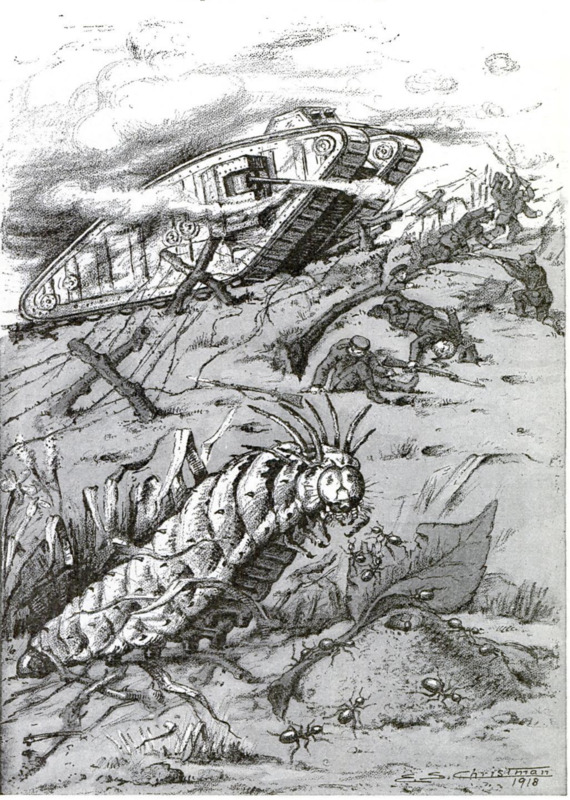

Why Tanks Are Giant Caterpillars. Armor? The caterpillar has it. Traveling treads? The Caterpillar has them too. Machine guns? It has a poison squirt-gun

-

extracted text

-

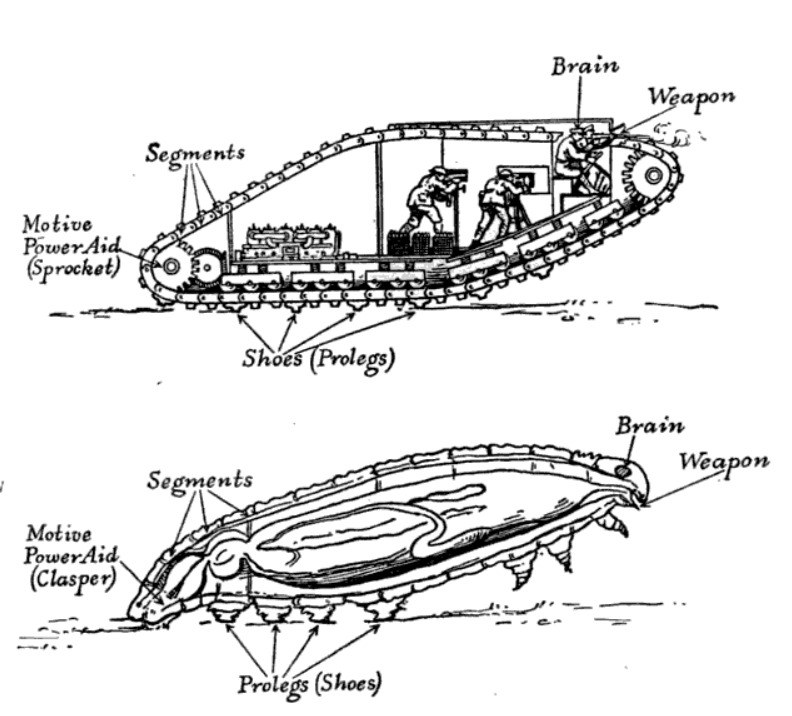

THE motion of the most formidable

and terrifying of modern war ma-

chines has often been compared with

that of the lowly larva from which comes

the radiant butterfly. This famed cruiser

of the battlefields might never have been,

but for the invention of the farm trac-

tor of Benjamin Holt with its caterpillar

tread. Through the courtesy of Captain

Haiz, of the British Army, who is here

demonstrating the pride of the English

arms, the writer was permitted to spend

nearly an hour within the Britannia, and

at every point he was more and more im-

pressed with the idea that not only does

the tank resemble the caterpillar in

movement, but that there are strange

likenesses in structure, in armor, and

even in control between the two objects.

The tank is a high-powered, armored

automobile differing from the war motor-

ear in that it moves not on wheels but on

two steel belts traveling on the heavy

‘metal frames on either side of its diamond-

shaped body. The belts consist of shoes

ingeniously linked together in endless

chains. Each shoe has a flange, with

which the tank can lay a firm hold on the

ground. The belts are fitted to heavy

sprockets. The rear sprockets are con-

nected by gearing with the powerful

engine in the back of the tank. The front

sprockets are idlers over which the belts

glide. There are also wheels which rest

on the upper surfaces of the belts. At

the top of the frames are rollers over

which the belts pass. The tank is really

laying down twin tracks or a railroad

of its own.

The body of the average caterpillar

consists of thirteen segments, four of

which belong to his thorax or, dropping

into mechanical terms, his fore compart-

ment, while nine are assigned to the

abdominal section. The number _of

segments varies with the species. The

chest portion has three pairs of true

legs, so called because they are well

jointed, easily controlled and muscular.

They are protected with horny sheaths

and are in eflect armored. With these

true legs the caterpillar can steer him-

self, help himself along a twig, or seize

leaves.

The pro-legs, or false legs, appear on

at Toast five of the segments, duly paired.

In their structure they resemble the shoes

of the tank belts to some extent and they

perform the seme functions. They are

fleshy _unjointed protuberances rather

than limbs. At the bottom of each one

are minute hooks which are used auto-

matically in giving the animal a hold on

the surface he is traversing. They are

for clasping, and in fact the rear pair are

50 modified as to be called claspers.

Now, if a caterpillar could keep his pro-

legs or shoes moving over his head and

over his tail in an endless chain arrange-

‘ment, his resemblance to the tank as far

as the locomotion details are concerned

would be perfect.

Some of the caterpillars have such a

rapid, undulating movement, that it ia

hard at first to analyze its elements. The

caterpillar actually walks by extending

and contracting the fleshy segments of

his body, the power being transmitted

‘mostly to his pro-legs.

‘Any one who has seen the fuzzy larvae

of the tussock moth going up a tree trunk

‘wil realize that the caterpillar is happy at

any angle. The same principle of construc-

tion illustrated in that insect permits the

tank almost to stand on end without los-

ing balance.

For the sake of simplicity, the wheels

at the rear of the tank by which it was

once steered have been discarded and

the direction is given by running the two

belts at different speeds. The landship

is rudderless. The caterpillar can twist

his segments at the jointures.

The observation facilities and guide

centres of both are in their forward com-

partments. The commander of a tank

and the driver sit well forward in the

Juggernaut, looking out of very narrow

slits. When it is necessary to close the

slits on account of rifle fire, the pilot

gropes his way as best he may. The

captain or lieutenant in command is the

brains of the steel-clad caterpillar.

Caterpillars have fairly active brainsand

a good workable ganglia, or nerve center.

On either side of the head they have small,

shining eyes inrows. They also get good

information about the nature of the

surface over

which they are

passing by low-

ering delicate

filaments or

sense organs

known as pa-

pill.

The British

tank is a terror

to the Teuton

infantry as it

starts relent-

lessly over No

Man's Land,’

crushing every-

thing within

its reach and

mowing down

the enemy. It

brushes aside

wire entangle-

ments, shatters

dugouts and

forts of reinforced concrete and slays

cowering wretches in the trenches whose

cries for mercy the men in the car of

death cannot hear. What the tank is to

modern battle, the caterpillar may well

be in the wars of the insect world.

Imagine what a vision of frightfulness

that hideous specimen of the larval state,

the hickory-horned devil, would be to

the human race, if he were enlarged to

tank size, approximately eight feet wide

and twenty-eight feet long! What a sight

to make men’s knees shake with fear,

with his waving antenne, his fierce and

gleaming jaws, his towering horns, his

beady eyes, and his ponderous bulk! He

would ignore all obstacles as he went

trampling and devouring over the plain,

his vertical mouth opening and shutting

meanwhile like a ponderous valve.

In the realm of twigs and leaves, the

ery “The Caterpillars are coming!” must

mean as much as the alarm “The Tanks!

The Tanks!” means to the Germans. The

caterpillar is not the inoffensive slug

which he often seems to be as we look

down upon him as he bestirs himself

across some woodland walk. His hide is

very thick, and underneath it is a heavy

layer of fat. The doughty warrior ants

coming out with their nippers to assail

him, do not worry him much. Up goes

the tank of the world underfoot, and

down he comes

with a swing

of the forward

part of his body

and a group of

his enemies are

crushed to

extinction.

Several varie-

ties of cater

pillars have

very effective

weapons of of-

fense. The spe-

cies from which

comes the swal-

low-tail butter-

fly mounts a

rapid-fire

poison-gas gun.

‘When he ishard

pressed by his

enemies he will

project from his

head a tube which looks not unlike the

barrel of a Lewis machine-gun, and dis-

charge an odor so offensive that insects

‘within scent of it curl up and die.

The camouflage of tanks and cater-

pillars is effective always. “Old Crusty”

at the western front and “Old Crawly,”

of the garden both resort to disguise.

The tank is often painted the hue of the

mire; the caterpillar assumes the tone of

the soil.

There scarcely seems a characteristic,

therefore, either of the fuzzy denizens of

the foliage or of the monster military

mechanisms which may turn the tide

of this war, which does not reveal that,

after all, the terrors of the terrain are

caterpillars titanic.

It seems, after all, as though “there's

nothing new under the sun.” We copy

the fish for submarines, the birds for

airplanes, and now the tank is just a

glorified caterpillar.

-

Autore secondario

-

John Walker Harrington (writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1918-04

-

pagine

-

556-558

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Filippo Valle

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)