Paintings for Training

Contenuto

-

Titolo

-

Paintings for Training

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Teaching Machine-Gunners to Fire at Art. How paintings worth thousands, the work of famous artists, are used to develop skill in gunnery

-

extracted text

-

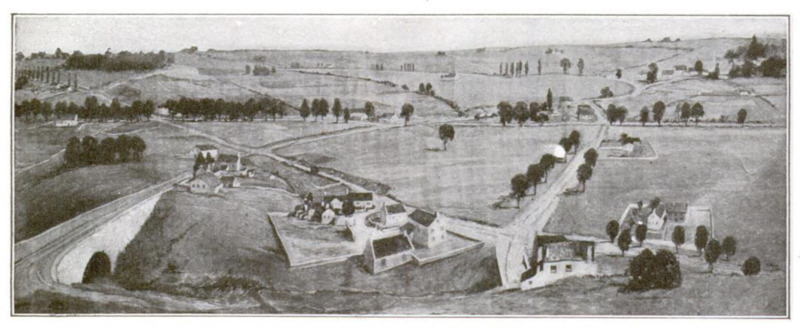

EVERY war has called in artists to help the fighters. Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and Benvenuto Cellini did their bit in their time, and now come the Academicians of our own day, whose ambition it is to paint landscapes at which soldiers will be glad to aim either cannon or machine guns. These scenic targets are works of art in every sense, for they must come from the skilled hands of masters of perspective and atmosphere and must be so ably composed that they serve just as well as long reaches of hill and dale and rolling uplands. The Art War Relief, an organization which has been enlisting noted painters for this all-important work, announced that the canvases of students and amateurs were not available.

Artificial Landscape Targets

Most young men are city or town bred. Hence few of the soldiers of our national army have a clear idea of distances in nature. As many of the cantonments have not been placed amid scenery like that which marksmen are likely to see “somewhere in France” or “on the way to Berlin,” artificial landscapes are provided on which they can practice. The paintings are too valuable for cannon fodder or even for machine-gun feed, but they serve wonderfully well in giving the illusion of panorama. The series which have been painted by H. Bolton and Francis C. Jones, both veteran members of the National Academy of Design, are typical of the kind of art which is now in league with war. Some of these pictures were used by machine-gun companies at Camp Upton near Yaphank, L.I., before their departure for overseas.

Distance and Proportion

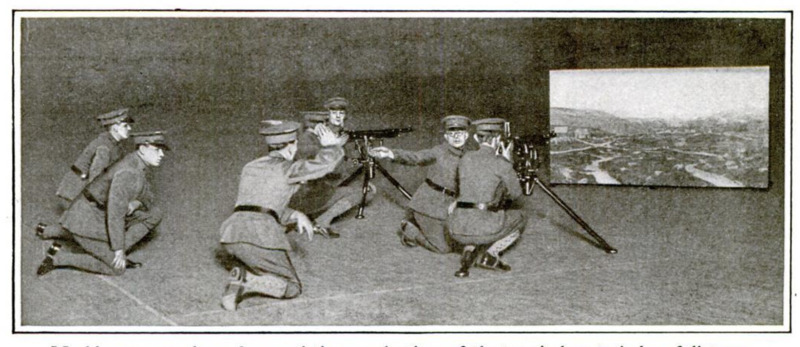

As the machine-gunners “lay on” their pieces in front of this pleasing mark they must keep in mind two things—range and close designation. The middle distance in the painting carries the normal vision back about 2,500 yards. The mountains far in the background are supposedly eight miles away and therefore out of range. The canvas is covered with houses and churches, bridges and culverts, and even a winding stream. The gunners aim their weapons at these various objects. The commander comes up behind them and points out errors they have made in sighting due in part to their untrained eyes and in part to their lack of familiarity with the mechanism.

How many men are there who grasp a description and act at once upon it? The officer gives the command, “Lay on black rock left clump of trees—three fingers!” Instantly the sergeant must repeat this order and see to it that the smooth barrel is so adjusted that it will guide bullets in the direction named. The quick understanding of the description of objects in a landscape can be developed by the use of the imitation terrain of paint. The firing of machine guns effectively is quick, sharp work and all the training of eye and brain which can be imparted stands the soldier in good stead in an emergency.

So exact are these high-art targets, owing to the co-operation of the military authorities and the designers, that even the complicated problems of strategy can be solved quickly by their use.

Grain Field a “Nest of Death”

After the marksmen have become more experienced they are assigned to devising ways for routing snipers out of hidden retreats supposed to be in all these mimic landscapes. The purpose is always to kill as many of the enemy as possible with the smallest amount of ammunition. Assume that there is in the center of one of the painted transcripts of nature a waving grain field, all golden in the sun, and enveloped in a mellow haze, as an art critic might see it. The machine-gun captain considers it as a yellow nest of death in the midst of which are certain big and deadly wasps, the stings of which are laying low comrades of another command. He cannot see exactly where the buzzing pests are straddled, but no time is to be lost. He gives the command to “traverse the field,” which means that his gunners so divide the whole expanse of nodding stalks among them, that the zones reached by the rain of bullets account for every square foot of the suspected area. The variation of fire is made by causing the individual gunners to tap their pieces gently, so that a difference of two inches at the end of a barrel becomes a large space with the widening angle reached in a distance of a mile or so. The method of tapping can be learned readily in front of one of the brush creations and a man who is quick of eye and hand may soon become very proficient.

Useful in Estimating Trajectories

The counterfeit countrysides serve just as well as the real ones in estimating trajectories of projectiles intended for a certain locality and in the mastering of much of the theory of gunnery practice. The mistakes of the tyro can be constantly corrected. As the canvases are becoming more and more exact in their proportions, they are considered already as among the indispensables. A British officer on seeing some of these examples of American skill at Camp Upton recently, remarked that if the Allies had had as good ones they would have been able to have killed more Germans.

-

Autore secondario

-

John Walker Harrington (writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1918-06

-

pagine

-

866-867

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Filippo Valle

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)