Fighting the air

Contenuto

-

Titolo

-

Fighting the air

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Fighting the air

-

extracted text

-

THREE miles above the Army proving grounds at Aberdeen, Md., a 300-mile-an-hour pursuit plane streaked at top speed across the sky. It towed a sleeve target, resembling the “wind socks” at airports.**

With cotton stuffed in their ears, spectators watched the Army’s latest antiaircraft gun go into action. Super-sensitive shells, detonated by contact or even by proximity, rocketed into the air at the rate of 120 a minute from the thirty-seven-millimeter (inch-and-a-half) weapon. A few seconds later, there was a direct hit—and the target vanished.

Modern antiaircraft artillery, as exemplified by guns like this, has turned the tables on the air raiders. No longer can bombers ignore ground defenses while raining death from the sky. Figures from European battlefields show that only one enemy plane was brought down by antiaircraft fire in the last European war to every five shot down by pursuit craft—but today that proportion has actually been reversed. One reason is the amazing improvement in range, mobility, and speed and accuracy of fire in antiaircraft guns developed since 1918. The other is the innovation of *“director” fire control*, a method of aiming the guns electrically, which has been developed to its highest degree of perfection in this country.

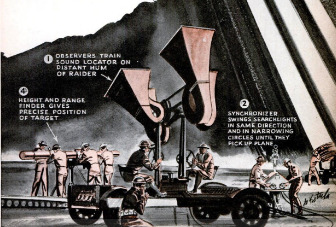

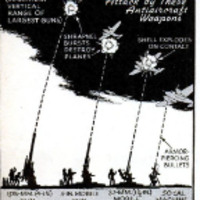

How the new *“director”* system works, in conjunction with a battery of four mobile guns that can be rushed to any threatened locality, is shown in an accompanying drawing. First warning of an approaching raider comes from a sound locator, whose great horns pick up the distant hum of motor and propeller. Observers train it on the source of the sound, and, at night, powerful searchlights swing simultaneously to pick up the craft for the gunners.

Then a trained crew brings into play an optical height-and-range finder, from which a trailing electric cable leads to a *“mechanical brain”*—a lightning calculator which automatically computes the firing data for the guns of the battery. Gunners waste no time by even glancing at their target. Reading dials mounted right on their guns, they aim the pieces accordingly, and a burst of devastating fire greets the hostile aircraft. The system works with such precision, experts declare, that it would be considered poor gunnery if more than fifteen shells were required to bring down a plane flying three miles high!

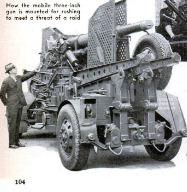

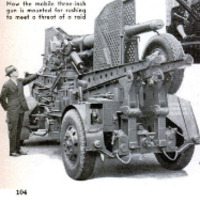

Except for larger, fixed antiaircraft guns that defend vital outposts like Hawaii and Panama, the Army’s standard weapon against high-flying planes is its mobile three-incher, of which more than 300 have recently been completed and many more are on order. Its shell, preset by a time fuse to explode at any desired altitude, wrecks a hostile craft with shrapnel.

For use against lower-flying aircraft, *“pom-pom”* and *“multiple pom-pom”* guns are a modern innovation. From clips or other automatic mechanisms, they fire a stream of 1.33-pound explosive shells—projectiles small enough to slip in your pocket—with almost machine-gun rapidity. A direct hit explodes a shell of this type. If it misses its mark, it destroys itself harmlessly while still in the air. The U.S. Army’s version of this potent new weapon, its new thirty-seven-millimeter gun, can be adapted to the same *“director”* control as the larger antiaircraft artillery.

-

Autore secondario

-

Alden P. Armaganac (writer of article)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1940-01

-

pagine

-

102-104

-

Diritti

-

Public domain

-

Archived by

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)