-

Titolo

-

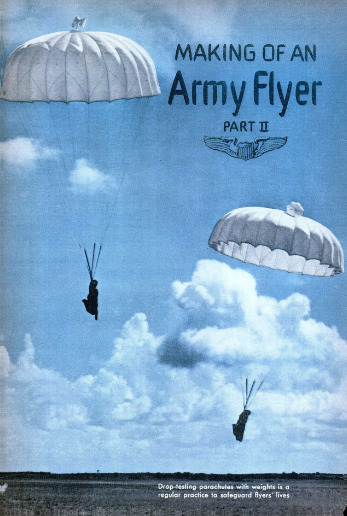

Making of an army flyer part II

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Making of an army flyer part II

-

extracted text

-

CADET RICK JONES LEARNS ABOUT NIGHT FLYING

AND HAS HIS FIRST EXPERIENCE WITH THE “JEEP”

THE night was black and moonless, but

as Flying Cadet Rick Jones sat at the

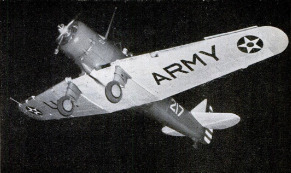

dual controls of his sleek Army BT-9

monoplane, it looked to him as if he

could reach up and pick a handful of stars

right out of the clear Texas sky.

His preliminary Air Corps training be-

hind him, Rick was now a student at Ran-

dolph Field, the great university at which

the U.S. Army prepares men to man its

modern fighting planes. Tonight he was

trying his hand at guiding his ship safely

through the darkness.

Two thousand feet below, the giant land-

ing field was the size of a pocket handker-

chief. The borders were outlined in green

markers and red obstruction lights, while in

the center of the field a faint patch of light

showed the area swept by the landing flood-

lights.

‘The roar of the motor was sweet and even,

the BT-9 responding to the controls with a

smooth precision. Compared with the light

PT-13 of his early training, it seemed like

driving a fast racing car instead of a truck.

At times he was almost frightened at so

much power under his throttle, but now he

was getting the feel of the ship. Three

nights of dual flying with his instructor had

given him confidence.

“He's giving me a free hand this time,”

he thought, missing the occasional reassur-

ing pressure on the controls—then realized

that only a sandbag ballasted the rear cock-

pit; that his instructor was down below in

the glass-windowed control tower, with the

dispatcher and other instructors whose ca-

dets were soloing tonight. Down there, he

knew, keen Army eyes were watching,

weighing him, testing his value to the na-

tion that was giving him its best here at the

famous “West Point of the Air.”

From time to time, in the distant sky,

tiny red and green lights moved and disap-

peared. Seven other cadets were practicing,

each in his own quarter of the sky—three

with Jones below the 2,000-foot level, four

safely above 2,500.

In his headset a hoarse voice rose above

the static: “Lower Zone 2, come in for a

landing.” Atop one of the hangars flashed

two parallel lines of red lights.

Rick flicked the radiophone to “Send”

position and replied into his microphone:

“Lower Zone 2 to Tower. Received O.K.”

Heading back in a descending spiral

toward the field, he lost altitude; laid his

course parallel to the base of the swiveled

wind T outlined in green lights, and de-

scended to 500 feet as he traversed the ima-

ginary “base leg” of his entrance to the

field.” A square turn headed him straight

into the wind. He cut his gun, lowered his

“air-brake” wing flaps, and settled rapidly

at the correct gliding angle.

Out of the dark rushed the plane, into the

slanting glare of the floodlights’ diagonal

beams. The landing wheels bumped and he

was taxiing rapidly over the field.

“Good landing. Now roll up your wing

flaps and go back to your zone.”

Rick cranked the handle of the flap con-

trols, pushed hard on the throttle, and again

raced into the blackness at sev-

enty miles an hour. As the jolting

stopped and the field dropped

away from his wheels, three red

bars flashed from the hangar top

and the headset said, ‘Lower Zone

3, come in for a landing.”

One after another, the eight ca-

dets went through their paces in

solving night problems, always

under the watchful direction of

the instructors who rode with

them or watched from the control

tower below.

Again Rick landed by the aid

of a 800,000-candle-power para-

chute flare, hurrying to reach the

ground before its unearthly bril-

liance failed. Then came the most

formidable problem of all—“wing-tip” land- |

ings, guided only by the beams from the

lamps sunk into recesses in the leading edge

of the monoplane’s wing. To make the sud-

den drop down into nothingness, down

toward a hypothetical landing field that was

merely a square black hole, was like jump-

ing blindfold from a high springboard. The

red line of marker lights rose and fell on the

horizon as he dipped and raised the nose of

the plane. Then a gray patch as the beams

began to reveal the surface of the field. A |

split seconds anxious suspense, a lightning

judgment of distance—then the bump of the

wheels, a sweep across the field, and off

to try it again.

The next day, a new problem was presented

as four G Flight cadets gathered about a

table in the hangar annex, looking over

the shoulder of the man at the microphone.

Across the wide chart upon the table crept

the “bug,” an instrument vaguely resem-

bling the workings of a phonograph. Upon

its three casters it sidled about like an an-

cient, cautious crab, leaving a narrow ink

track in its wake.

From the bug a small cable trailed across

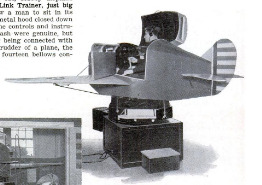

the room to a fat, stubby airplane

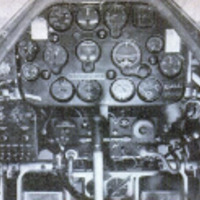

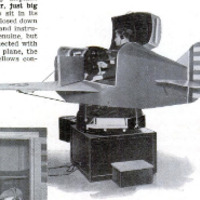

known as the Link Trainer, just big

enough to allow a man to sit in its

cockpit with a metal hood closed down

over its top. The controls and instru-

ments on the dash were genuine, but

instead of their being connected with

the motor and rudder of a plane, the

“jeep” rode on fourteen bellows con-

cealed in its base. When the pilot of this

unique craft pulled the stick back, the nose

began to lift and the altimeter needle kept

pace with its upward “flight.”

For all practical purposes, the jeep was a

real airplane. In it every cadet must get his

initiation into blind flying; every Army

pilot, regardless of rating, must spend a

given number of hours in it each year to

keep in practice

Even swank colonels with eagles on their

shoulders had to come in for regular drill in

navigation and blind flight.

The cadet in the jeep was having trouble

with his turns. The indicating wheel was

tracing a snake track as he tried to straight-

en his course.

“A fellow ought to be able to fly a simple

compass heading,” criticized Sanders. He

had owned a small cabin monoplane at twen-

ty and felt himself an old hand at flying.

Ryan gave him a sidelong glance, “Ever

fly under the hood?”

“No, but anybody who has had twenty

hours in the air should be able to make

ninety and 180-degree turns with his eyes

shut. If you keep your ailerons even, it's

just like steering a bobsled, only you move

your feet the opposite way. What's hard

about that?”

The plane leveled itself, the hum stopped,

the hood lifted, and “Chubby” McElroy’s

round head emerged from the cockpit. He

mopped a pink face with a handkerchief as

he stepped down.

“What's the matter, Lindbergh? Didja

get lost at sea?”

“Corrigan, you mean,” corrected another

cadet. “He started for Philadelphia and

landed in a duck pond west of Cincinnati.”

“All right,” cut in the instructor. “Put

‘em back in the hangar, you barracks pilots.

Who wants to start on his jeep time?"

“C'mon, Sanders,” urged Ryan, with sus-

picious enthusiasm. “Show the rest of us

dodoes how to do it.”

Sanders grinned confidently, swung a long

leg over the cockpit, dropped into the seat;

and pulled the “ignition” switch. The fan in

the front of the fuselage sent a brisk breeze

whistling past his ankles. He clamped the

headphones over his ears, swung the hood

down tight, and the group at the table heard

his “Ready!” from the instructor's head-

phones.

“Climb to 2,000 feet and make a ninety-

degree turn to the left,” said the instructor.

The jeep's elevators lifted, the nose

pointed upward; the hum of the blower in-

creased. Then soon the jeep leveled off and

began to edge to the right as the rudder

bent slightly.

G Flight's instructor turned to Rick.

“Jones, if he makes a one-needle turn at 130

miles an hour, how long will it take him to

turn ninety degrees?”

“Thirty seconds, sir.”

“Right. Watch your clock, Sanders.”

By now the indicator had traced a square

turn on the chart. But even as it straight-

ened, it began to edge back again, leftward.

In a moment the pilot realized his mistake

and corrected it. But soon the rudder shifted

back and again he was off to the left. Then,

in a few seconds it made an equally wide re-

turn to the right. The indicator was tracing

a curly spiral on the chart.

“He's tightening up on the turns. Now

watch this.”

Suddenly the nose jerked quickly to the

left as Sanders gave an impatient flip of the

rudder bar. Brought up too sharply on a

turn, the jeep promptly slipped off and nosed

into a spin. Around and around it went, the

pilot fanning the air with the controls and

vainly trying to pull out.

About the table, grins widened. The in-

structor bent toward the microphone.

“You'll have to neutralize your controls,

Sanders. . . . Keep your air speed up—she

stalls below sixty-five mph. . . . That's the

idea. Now pull her out.”

The spin stopped, but in an instant, San-

ders was off in the other direction, around

and around.

“Well, make up your mind,” said the in-

structor softly. “Are you going to fly it by

instrument or by the seat of your pants?”

The jeep's controls shrugged compliance.

“All right. Now pull your rudder over to

the right until the compass reads ‘East’.

Sanders obeyed and the jeep leveled out

into even flight.

“Now how are you getting along”

“I'm still spinning!” was the startling an-

nouncement. G Flight doubled up in silent

laughter.

“Well, guess you'd better come down if

that's the case,” replied the instructor. A

moment later a very red-faced cadet lifted

the hood. His jaw dropped as he noticed his

stationary surroundings.

“Bail out, Sanders, you're going to crash!”

Helpful hands reached up with exag-

gerated solicitude, to help him down. San-

ders waved his arms in surrender.

“All right, all right, I give up! So far as T

can see, I'm still in a spin, but I guess may-

be those instruments know what they're

talking about. Maybe a bobsled is a better

proposition for flying by the seat of the

pants than an airplane, after all.”

Next month, Sterling Gleason will tell how

Rick Jones completed his training and re-

ceived his wings as a full-fledged Army

flyer.

-

Autore secondario

-

Sterling Gleason (article writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1940-02

-

pagine

-

120-124, 239, 241

-

Diritti

-

Public domain

-

Archived by

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-06 15.53.37.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-06 15.53.37.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-06 15.53.47.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-06 15.53.47.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-06 15.53.56.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-06 15.53.56.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-06 15.54.01.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-06 15.54.01.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-06 15.54.10.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-06 15.54.10.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-06 15.54.17.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-06 15.54.17.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-06 15.54.24.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-06 15.54.24.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-06 15.54.32.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-06 15.54.32.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-06 15.54.45.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-06 15.54.45.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-06 15.54.53.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-06 15.54.53.png