-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Uncle Sam groom his hell buggies

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Uncle Sam groom his hell buggies

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

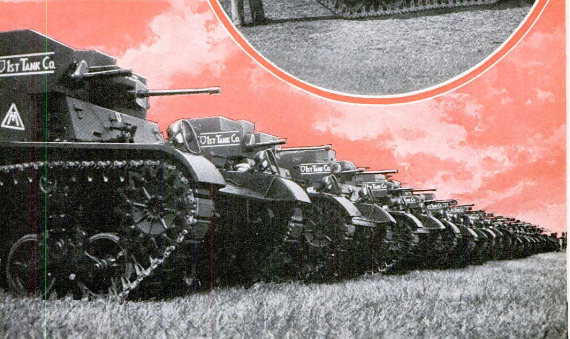

ONE cold morning this win-

ter I stood in a big, open

field at Fort Hoyle, Md.,

talking about tanks with Lieut.-Col. B. G.

Chynoweth, who commands the First Bat-

talion of the G6th Infantry, the Regular

Army light-tank regiment which traces its

history back to the American Tank Brigades

‘which fought in Belgium and in the Argonne

two decades ago. Near us a long line of

tanks stood waiting; 600 yards away, where

scrub and brown underbrush edged the field,

men were working over a bullet-scarred,

paintless old Renault which, crewless, was

serving as a moving target for its offspring.

“Take a ride in one of the tanks,” the

Colonel invited. “That's the best way to get

an idea of what they're like.”

‘When I lowered myself through the turret

port—a tanker needs to be a fair sort of

acrobat —into the right-hand front seat, the

sergeant who was driving gave me a friend-

ly grin. The inside of a tank with its engine

running isn't the best place in the world for

verbal amenities. There wasn't any room to

spare, but the steel walls were painted

white, and with the driving and turret ports

open the interior was light.

‘The sergeant manipulated one of his steer-

ing levers after the other and nudged his

eleven-ton steed around sharply. We began

to move forward, picking up speed quickly.

The motion over the fairly rough field was

noticeable but not unpleasant—a sort of

easy pitching, like the motion of a small

boat when a ground swell is running. I

thought that we were going about twenty-

five miles an hour, but later was told that

we had been doing a good thirty-five. When

we reached the end of the field the sergeant

swept his tank around in a wide turn. Then

we roared back up the field, turned sharply,

and nosed into our berth at one end of the

firing line as neatly as a sport roadster

could have done it.

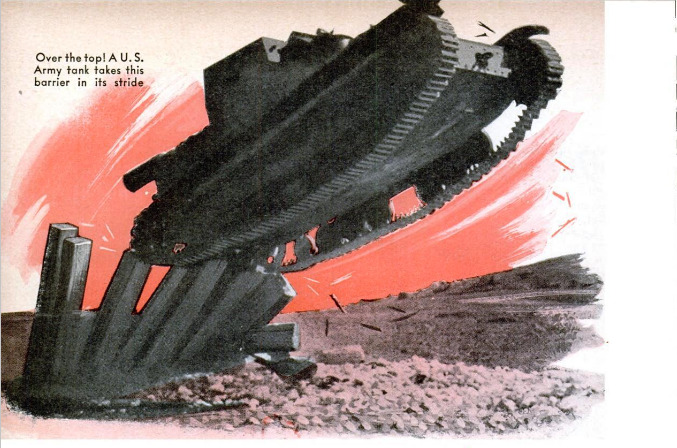

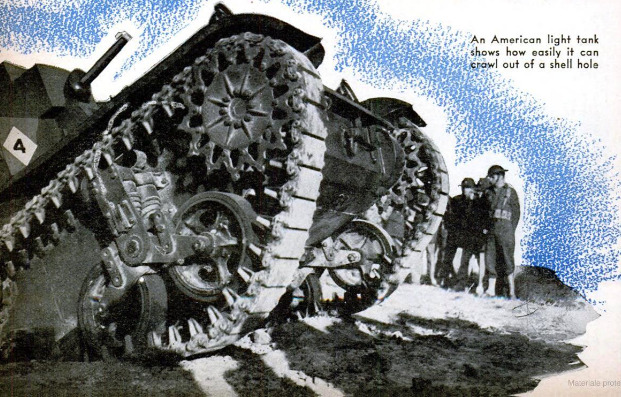

Of course, riding in a tank over an open

field isn't anything like riding in a tank over

the sort of terrain on which tank battles are

likely to be fought—rough cround made

rougher by being well cut up with trenches

and shell holes and by being strewn thickly

with obstructions of various unpleasant

Kinds. And the interior of a tank with its

ports open isn't anything like the inside of a

Tullcrewed tank Wilh Tis Torts closed for

BOTLON=W IIIS TON Wo (now lyon.

experience told me, can be very hot

when bullets are spanging on its

steel sides. Tankers are

trained and hardened to

“take it” over the roughest

ground under simulated bat-

tle conditions.

Colonel Chynoweth asked

me if I'd like to try a few

bursts at the old Renault,

which had been headed 50

that it would run across the

field in front of the lined-up

tanks. I moved back to the rear seat, which

is somewhat higher than the front seat, and

one of the officers showed me how to wedge

myself in behind the 30 caliber turret

machine gun. You fold your right leg under

you and kneel on the seat, brace your left

Toot solidly against the steel floor plate, and

press your back hard against the back of the

turret. That settles you as solid as a rock,

bringing your shoulder snugly against the

gun butt ‘and your right eye close to the

sight tube alongside the barrel. Horizontal

and vertical hair lines divide the sight's

eyepiece into four quadrants, and the gun is

mounted so that only slight pressure is

needed to change its elevation or to traverse

its muzzle across a wide field of fire.

While I was getting acquainted with my

gun, the sergeant had switched off

his engine and was getting set to

do a little shooting with the .50

caliber machine gun in the other

turret. “Get the nose of the tank

in the upper right quadrant and

you'll sock her,” he advised. Look-

ing through the narrow eye slit

above the gun I saw that the old

Renault had been started and was

rumbling briskly across the field.

It seemed a lot smaller than it

had a minute earlier. When I

squinted through the sight the

tank looked even smaller. At 600

yards it blended into the drab

scrub behind it, and smoke from

underbrush which had been set

afite by tracer bullets on an

earlier run didn't make the target

any clearer.

I got the tank's nose in the

upper right quadrant, and pressed

the trigger. The gun went fat-

tat-tat, and the fiery tracer bullets

told me that I was shooting high and to the

right. I swung the muzzle down and to the

left—and couldn't find the tank! All I could

see through the sight was a vague cloud of

brown dust kicked up by bullets from the

twenty-odd machine guns which were firing.

I aimed at the dust cloud, but I don't think

1 hit anything in it.

When I had fired all my shots T watched

through the eye slit. Near the end of its

run the tank came clear of the dust cloud

and some gunner got squarely on his target.

You could see the tracer bullets bouncing off

its armor into the tree tops, like red balls

out of a Roman candle. The cease-firing

whistles sounded, but that old Renault kept

right on going. The long wire, connected

with its engine switch, which it had been

trailing behind had been cut by a bullet.

The tank crashed into the underbrush and

wallowed slowly along until a fair-sized

tree stopped it.

The Colonel took me down to have a look

at it. Nothing interests tankers

more than seeing what bullets

can and can't do to their tanks.

The ancient Renault's armor

was scratched and dented by several hun-

dred machine-gun bullets, but not one of

them had gone through it.

My close-up of tanks at work taught me

three important things about them: that

they can move fast, that they aren't easy to

hit, and that if their armor is moderately

heavy they aren't very likely to be hurt by

machine-gun or rifle fire.

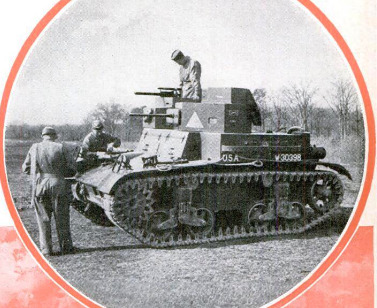

‘While the U. S. Army can't compare with

European mechanized forces in number of

tanks, American officers are confident that

we are away ahead of them in quality—that

in the M2A1 model tank now being built we

nave the best light tank in the world. Driven

by a powerful airplane-type, air-cooled en-

gine, it has a road speed of above thirty-five

miles an hour and a correspondingly high

cross-country speed. Its armor is heavier

and its tracks longer than the present

standard light tank, and in addition to four

machine guns it carries a 37-millimeter

cannon. The tracks, driven by

sprockets and rolling over four

bogie wheels on each side which

support the weight of the vehicle,

are made of a long-wearing, heat-

resisting rubber composition set

in steel blocks. Its engine, trans-

mission, drive, and tracks all are

considered superior to those of

any foreign tank.

The medium tank now being

built

also is of advanced design. It is heavier,

more heavily armored, and a more powerful

all-around fighting weapon than the light

tank, but it isn't nearly so fast on the road,

and its use is restricted to districts where

the bridges can bear its increased weight.

Our army has no very heavy tanks—the So-

called land battleships built for special

purposes by some European armies,

The tank is the offense’s answer to the

defensive power of the machine gun. The

defense has found several answers to the

offensive power of the tank. Most spectacu-

lar of them is the quick-firing antitank gun.

The model now being produced for our

Army is of 37-millimeter caliber and its

two-pound shells pierce an inch and a half

of modern armor at 1,500 yards. Other

armies have similar weapons.

Attacking infantry advances at the speed

of about two miles an hour. On average

ground, tanks come under direct fire from

antitank guns at a range of about 1,000

yards. So if the tanks limit their speed to

the speed of the infantry, they are under

direct fire of weapons capable of destroying

them for seventeen minutes. If they ad-

vance at their top cross-country speed of

about thirty miles an hour—which wouldn't

often be possible in war—the danger period

is reduced to a little over a minute. The

light tanks now being built carry a 37-

millimeter gun of their own for use against

machine-gun emplacements and antitank

guns, and perhaps against enemy tanks.

At long range, a gun on the ground has an

advantage over a tank; at short range, a

tank has an advantage over a gun on the

ground. The quicker tanks can get to close

quarters, the more likely they are to win. No

matter how fast they are, some of them will

be knocked out by artillery or antitank-gun

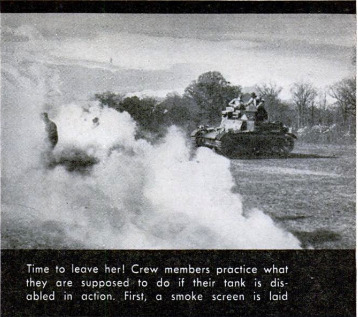

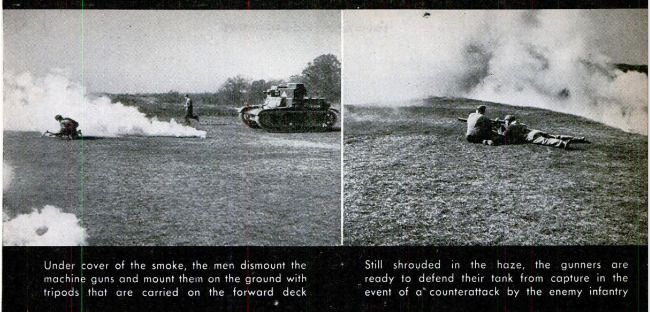

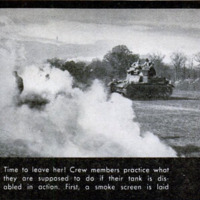

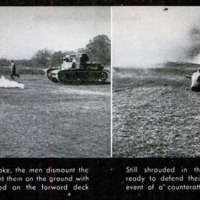

fire. Tankers are trained to act fast when

it is time to “leave her’—to get out on the

ground with their machine guns and pro-

tect their disabled tank against capture.

The American idea is for the tanks to go

in at the best speed possible, and to reach

and cruise over their objective while in-

fantry supports them with its fire and the

artillery concentrates on the enemy's anti-

tank guns. After the tanks have destroyed

the enemy machine-gun nests the infantry

will be able to filter forward with slight

losses. Bullheaded hammering against im-

pregnable defenses has no place in the

‘American conception of tank tactics. A tank

attack should be a swift, surprising, and

hard-hitting blow where it will hurt.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Arthur Grahame (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1940-02

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

76-79, 231

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 136, n. 4, 1940

Popular Science Monthly, v. 136, n. 4, 1940