-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Uncle sam remodels his army

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Uncle sam remodels his army

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

BOMBERS rain destruction down on

him out of the high air, and low-

flying hedgehoppers pepper him

with their machine guns. Fire-

belching tanks lurch menacingly

toward him through early-morning battle

field mists. Field guns spray him with dead-

ly shrapnel, and howitzers pulverize his

trenches into gory ruin with high-explosive

shells. In the World War he was drenched

with poisonous gases and—ever a cheerful

pessimist—he fully expects to be drenched

with them again in the future. When he

marches he plods along stubbornly under

a burden of equipment, weapons, and am-

munition which, in its proportion of weight

of load to weight of bearer, is twice the

burden of an army mule. When he fights

on the defensive he keeps his head down and

hopes for the best in a trench which nearly

always is muddy. When he attacks he goes

grimly forward against all the nerve-shat-

tering hellishness of modern war machines

protected by nothing more substantial than

atin hat.

The Britishers call him the poor bloody

infantryman. The French call him the

poilu. We call him the doughboy. He has

won every war—barring push-overs such as

the German-Polish blitzkrieg—which has

been fought since gunpowder began to make

steel-plated knights look silly toward the end of

the Middle Ages. Despite airplanes, gas-engine-

propelled armored fighting vehicles, high ex-

plosives, chemicals—all the products of science

and of human ingenuity which have been pros-

tituted to the uses of destruction—he remains

the king-pin of battle. Because only the foot

soldier can both take ground and hold it, it is the

infantryman that wins the local successes which

make it possible for generals to win the battles

which enable nations to win wars.

Over a century ago Napoleon said: “The in-

fantry is the army.” Today high-ranking Amer-

ican Army officers almost unanimously chorus

“check!” to that observation.

‘The fact that they agree with Napoleon doesn't

‘mean that these officers are 100 years behind the

fast-moving military parade. They have studied

all the new weapons which, a few years ago,

‘many people thought would reduce the infantry-

man to the ignoble role of a mere mopper-up,

and they have experimented with most of them.

They all believe in artillery—plenty of it. They

all believe in airplanes, although they don’t agree

on how aviation should be used in war. They all

believe in motorization—even the tradition-lov-

ing yellow-legs who want to do their fight-

ing ‘on horseback are glad to have their

mounts carried to the scene of action in

trailers. Most of them shrug their shoul-

ders at the prospect of chemical warfare,

and have no qualms about using gas if the

other fellow uses it first. Nearly all of them

believe in mechanization, in greater or less

degree. But with the exception of a few

wing-wearing enthusiasts who are honestly

convinced that air power could win any war

all by itself if it only were given a real

chance, these men who have made a study

of modern war believe that the new weap-

ons that the machine age has given soldiers.

should be used for just one purpose—to help.

the infantry to advance. It still is the dough-

boy that lands the knock-out, they say. It

still is the infantry that is the core and es-

sential substance of the army.

‘When we went into the World War the

organization of our small infantry divisions

had to be changed to meet the demands of

the murderous toe-to-toe slugging match on

the Western Front, where continuous trench

lines from the sea to Switzerland gave no op-

portunity for maneuvering. Fast footwork

‘was sacrificed to develop a hefty punch, and

the infantry division—composed of two two-

regiment brigades of infantry, a three-regi-

ment brigade of artillery, and various aux-

iliarles—was strengthened until in the final

months of fighting its authorized strength

was close to 30,000 men. Those big World

War divisions moved slowly, and keeping

them supplied with ammunition and food

was a job which turned staff officers’ hair

gray, but they could take a lot of punish-

ment, and they packed a mighty wallop.

After the World War another reorganiza-

tion was indicated. What our army needed,

military experts decided, was infantry divi-

sions that were small

enough to move fast and

large enough to hit hard.

Various Staff officers

went to work on the reorganization

problem. One of them was George

Marshall, who at forty-odd still was

a Regular Army captain, although in

France he had worn a colonel’s silver

eagles when as Chief of Operations of

our First Army he had planned the

withdrawal of our troops from the St.

Mihiel battlefield and their transfer to

the new positions from which they

launched the decisive Meuse-Argonne

offensive—a _fourteen-day-long _mili-

tary juggling act which gave the Ger-

man General Staff its most complete

and unpleasant surprise of the war.

Marshall was the original army

streamliner. He started with the in-

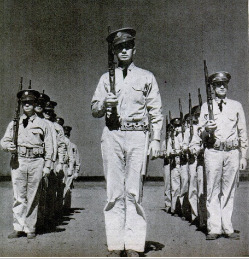

fantry squad, and worked up. He was

the father of the new simplified in-

fantry drill regulations which enable

a commander to move his men from

where they are to where he wants

them and get them fighting with a

maximum of speed and a minimum of

frills, and

‘which make it possible for an instructor to

teach recruits all they need to know about

close-order drill in a few hours. The new

regulations remained tentative and experi-

mental for the better part of ten years. They

became official a few days after General

George Marshall was appointed Chief of

Staff last year.

Staff officers continued to sweat over new

tables of organization for the infantry divi-

sion—the basic organization of the Army,

but they were unable to evolve anything

which seemed more efficient than the old

World War “square” division. By pruning

the muster rolls of the regiments they re-

duced the division's peace strength to 13,500

and its war strength to 21,500. Efforts to

make it still smaller in the interest of in-

creased mobility were blocked by the then

unanswerable contention of experienced of-

ficers that further reduction would result in

a fatal loss of fire power—that the fighting

value of an infantry division shouldn't be

measured by how fast it can move, but by

how many men it can put on its firing line.

It was, oddly, a civilian that provided the

answer to the soldiers’ argument and who

made the Army's new “streamline” division

practicable. His name is John C. Garand,

and he is an employee of the Government

armory in Springfield, Mass. The answer he

provided is a gas-operated semiautomatic

rifle which is believed to be the best mili-

tary shoulder weapon in the world.

Assuming that 100 men armed with the

Garand can produce a volume of fire equal

to that of 250 men armed with any rifle

used by the infantry of any other army, the

General Staff ordered the organization of

five “streamline” divisions which can hit

hard as well as move fast.

There are no brigades in the new division,

which is known officially as the “triangular

division.” It is composed of three regiments

of infantry, two regiments of field artillery,

a division headquarters and military-police

company, an engineer battalion, a quarter-

master battalion, a medical battalion, and a

signal company. With the additional medi-

cal personnel attached to its various organi-

zations, its authorized peace strength is

8,953 officers and men, but as 390 are in-

active in peace, its actual peace strength is

427 officers, three warrant officers, and 8,133

enlisted men—a total of 8,563. Its war

strength is about 12,000. Its 1,257 motor

vehicles—trucks, tractors, field cars, trail-

ers, motor cycles, and motor-cycle side cars

—can transport or tow all its artillery,

heavy weapons, and equipment, and also

carry a considerable number of its men.

Certainly its fleet of motor vehicles will in-

crease its marching rate considerably above

the twelve and a half miles a day which was

normal for the foot-slogging, mule-drawn

World War division.

The streamline division's three infantry

regiments are the backbone of its fighting

power. Each of them has an actual peace

strength of 1,964 officers and men, and a war

strength of about 2,400. At war strength

each regiment would have 1500 Garand

rifles in its firing line.

The organization of the infantry regi-

ment is triangular. It has three battalions.

Each battalion has three rifle companies and

a heavy-weapons company armed with six-

teen .30 caliber machine guns, two .50 cali

ber machine guns, and two Sl-millimeter

mortars—smoothbore, curved-fire weapons

which can lob a 71%-pound fin-type projectile

two miles. Each rifle company has a head-

quarters platoon armed with three 60-milli-

meter mortars—light mortars which fire

a 3.3-pound projectile to a maximum range

of about a mile with remarkable accuracy

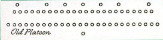

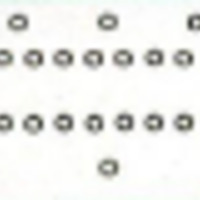

—and three rifle platoons. Each rifle pla-

toon is composed of three rifle squads of

eight men each at peace strength and of

twelve men each at war strength. All the

members of the rifle squads are armed with

the Garand—or will be as soon as enough

Garands are available. The 15%-pound au-

tomatic rifles which were distributed one to

a squad under the old infantry organization

are out. So are rifie grenades.

For protection against tank attacks,

the regimental headquarters company is

equipped with six of the new 37-millimeter

cannon which are capable of thirty shots a

minute and whose two-pound shells will

“kill” any light or medium tank at 1,500

yards. Weighing only 900 pounds, and

mounted on pneumatic-tired carriages, they

are easily handled by an eight-man squad.

One of the new division's completely mo-

torized artillery regiments has thirty-six

75-millimeter guns which, modernized, have

a range of almost eight miles. The other

regiment has sixteen 155-millimeter how-

itzers.

Our new infantry division is the smallest

of any in the world's armies. The war

strength of the French division is about 14,-

000, of the German division about 15,000, of

the Italian division about 17,000, and of the

British division about 19,000. But our stream-

line division's 4,500 Garand rifles give it

greater fire power than that of any of the

European infantry divisions. And it is fire

power, not the number of men used to pro-

duce fire power, which is the real measure

of an infantry division's strength.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Arthur Grahame (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1940-07

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

82-85,218-219

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 137, n. 1, 1940

Popular Science Monthly, v. 137, n. 1, 1940

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-18 14.06.24.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-18 14.06.24.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-18 14.06.08.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-18 14.06.08.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-18 14.06.17.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-18 14.06.17.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-18 14.06.31.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-18 14.06.31.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-18 14.06.40.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-18 14.06.40.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-18 14.06.46.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-18 14.06.46.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-18 14.06.51.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-18 14.06.51.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-18 14.06.58.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-18 14.06.58.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-18 14.07.03.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-18 14.07.03.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-18 14.07.20.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-18 14.07.20.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-18 14.07.24.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-18 14.07.24.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-18 14.07.31.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-18 14.07.31.png