-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Flyers by the ten thousand

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Flyers by the ten thousand

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

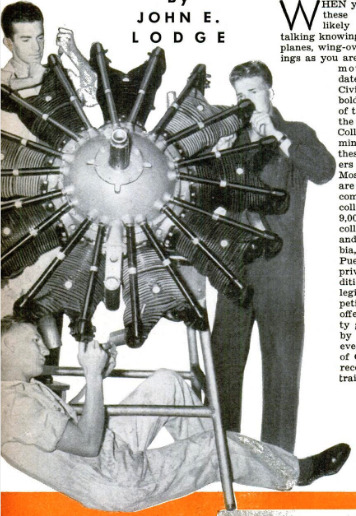

WHEN you walk across a campus

these days, you are quite as

likely to hear undergraduates

talking knowingly about low-wing mono-

planes, wing-overs, and cross-wind land-

ings as you are to hear them discussing

mouse-trap plays, heavy

dates, or passing marks. The

Civil Aeronautics Authority's

bold and successful venture

of training youthful fiyers by

the thousands has made John

College and Jane Coed go air-

minded. Don't think that

these collegiate aviation talk-

ers are mere “hangar pilots.”

Most of them are flyers, or

are well on the way to be-

coming fiyers. During the

college year of 1839-40 about

9,000 of them, enrolled in 437

colleges located in every state

and in the District of Colum-

bia, Alaska, Hawaii, and

Puerto Rico, earned their

private-pilot licenses. In ad-

dition, well over 700 noncol-

legians, winners of com-

petitive flight scholarships

offered the students in seven-

ty ground courses sponsored

by civic organizations in

every state and in the District

of Columbia and Alaska, are

receiving exactly the same

training.

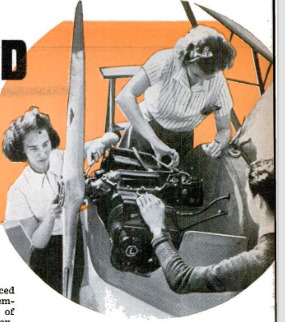

When this nation-wide training

effort was started last fall, its pri-

mary objective was to accelerate

the already swift progress of civil

aviation in the United States by

teaching large numbers of young

men and women to handle their

own airplanes safely in either

pleasure or utility flying. A second-

ary objective was the building up

of a reserve of physically sound,

partially trained pilots for possible

service in the Army or Navy in the

event of war.

The swift and menacing march

of world events in the past few

months has brought about a re-

versal in the degree of importance placed

on these objectives. Now most of the em-

phasis is on the national-defense aspect of

the program, which has been greatly ex-

panded. In the course of the coming year

the C.A.A. courses will give ground and

primary flying training of 45,000 students

in three intensive courses, each of which,

instead of being spread over the school year,

will be compressed into four months. In

addition, the 9,000 1940 graduates—over

ninety percent of them have indicated their

desire to become military fiyers—will be

given forty-five-hour advanced courses in

faster planes than those which are used for

the primary training.

The Civil Aeronautics Authority, the

Government agency charged with the regu-

lation of civilian aviation, has mo direct

connection with the armed services. The

graduates of its flying courses are not com-

bat flyers, and have no military obligations

which are not shared by nonflyers of the

same age. But the training they receive

is the equivalent of the flying training given

Army and Navy flying candidates, and it

will enable many of them to qualify as com-

bat flyers after six months of advanced

specialized training in service flying schools.

When the project of providing wholesale

flight instruction first was considered late

in 1038, an abnormally high percentage of

student-fiyer accidents was helping to make

private flying, with a safety rate of only

750,000 miles for each fatality, the most

hazardous form of aviation. But careful in-

vestigation indicated a method by which

‘mass production of pilots might be achieved

with a high degree of safety. It was found

that the students of flying schools which

had thorough ground courses and sound

flight courses suffered far fewer fatalities

than did the graduates of schools whose in-

struction standards were lower.

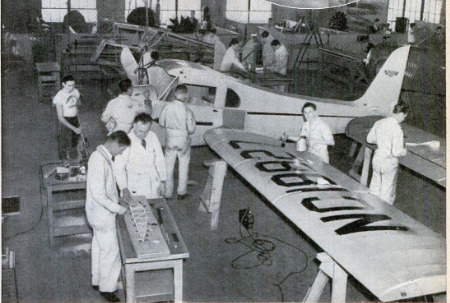

Placing heavy emphasis on safety, C.A.A.

experts worked out a ground course which

would teach students why and how

airplanes fly, and a flight course

which would enable instructors to

nip bad flying habits in the bud. In

the spring of 1939, with $100,000 of

National Youth Administration funds,

a test program was started in thir.

teen selected colleges. Undergradu-

ates enthusiastically grabbed at the

chance to learn to fly—so enthusi-

astically that at the University of Alabama

there were 1,200 applicants for the thirty

places in the class. A total of 330 students

with high physical qualifications were ac-

cepted at the thirteen participating colleges.

All of them reached the solo stage and 317

won private-pilot licenses. Their average

flying time to the certificated stage was

thirty-eight hours, and they flew a total of

1,200,000 miles with only a single fatality.

Convinced by this ex-

perience that the way

to increase the safety

of flight instruction was

to raise the quality of

the instruction, the

C.A.A. standardized its

ground and flying

courses and required all

airmen holding flight-

instructor ratings to

familiarize themselves

with the improved instruction methods and

to pass an examination to prove that they

had done so. More than 4,000 instructors

passed the test, assuring the Authority of

plenty of highly-qualified teachers for its

training program.

Congress passed a Civilian Pilot Training

Act and provided $4,000,000 for the 1939-40

courses. Undergraduate interest was so

keen that colleges ranging from stately ivy-

covered institutions to little city and junior

colleges offered the pilot-training courses.

When school opened last September, over

9,300 undergraduates who had passed the

searching physical examinations given by

C.A.A. flight surgeons were accepted as

students. By June they had logged 310,000

dual and solo flying hours—almost 22,000,-

000 miles—with very few mishaps and only

one fatality. That remarkable record is animprovement

of 3,700 percent over thesafety record for flight training for the

whole country only a year ago!

‘Under the terms of the Civilian

Pilot Training Act at least five

percent of those enrolled for the

courses must be noncollege stu-

dents. To provide instruction

for these, the C.A.A. enlisted

the cobperation of chambers of

commerce, university-extension

services, American Legion posts, aeronauti-

cal associations, and civic clubs in com-

‘munities of every state. The ground courses,

which are exactly the same as those offered

in the colleges, are open to anyone, but, to

be eligible for one of the ten flight scholar-

ships offered with each course, the student

must pass the same physical examination

given the col-

most deadly enemy of good flying. They

are alert for indications that the student is

“choking the stick’ getting a drowning

man’s clutch on the control. This prevents

the development of the delicate “feel” by

which good pilots fly.

During early dual flights the instructor, in

the front seat, demonstrates simple maneu-

vers and the student follows his movements

on the dual controls. Then the student is al-

lowed to fly the plane except when taking

off and landing, with the instructor ready to

take over if he makes a serious mistake.

In the later lessons of the dual-instruction

stage the instructor demonstrates spins and

simulated forced landings, and the student is

permitted to make into-wind take-offs, and

into-wind landings without power.

As soon after the minimum eight hours

of dual instruction as the teacher thinks he

is competent, the student makes his first

solo flight. He devotes at least six half-

hour periods, with as much dual check in-

struction as his instructor thinks desirable,

to practicing level flight, turns, glides, and

other elementary maneuvers. Then he goes

on to advanced solo flight and devotes fif-

teen hours in the air, checked by eight hours

of dual instruction, to precision landings,

stalls and spins, power turns, cross-wind

take-offs and landings with power, and oth-

er advanced maneuvers, leading up to a

fifty-mile cross-country solo flight over a

triangular course, and finally to the exami-

nation for his private-pilot license.

The Civil Aeronautics Authority's pilot-

training program has been sensationally

successful in training a large number of

pilots with a hitherto unknown degree of

safety. It is expected that during this com-

ing year at least 600 colleges will offer

C.A.A. courses to their undergraduates, and

that there will be a proportionate increase

in the number of noncollege courses. Many

of this spring's graduates intend to enter

Army or Navy flying schools after they

have completed their advanced courses this

summer.

Already the program has helped material-

ly to increase the number of licensed pilots

in the United States from 33,000 to 45,000

in less than a year. Aviation experts are

confident that the expanded program will

provide 1 large number of well-grounded

candidates for commissions in our naval

and military air services, and that many of

its graduates will become pilots of the new

fighting planes on which some day the safe-

tv of America may depend.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

John E. Lodge (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1940-09

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

46-51, 219

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 137, n. 3, 1940

Popular Science Monthly, v. 137, n. 3, 1940

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-31 13.54.57.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-31 13.54.57.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-31 13.55.08.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-31 13.55.08.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-31 13.56.04.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-31 13.56.04.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-31 13.56.16.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-31 13.56.16.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-31 13.56.21.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-31 13.56.21.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-31 13.56.26.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-31 13.56.26.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-31 13.56.34.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-31 13.56.34.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-31 13.56.43.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-31 13.56.43.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-31 13.56.50.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-31 13.56.50.png Ekran Resmi 2022-01-31 13.56.55.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-01-31 13.56.55.png