-

Titolo

-

New experiments with rockets

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

New experiments with rockets

-

extracted text

-

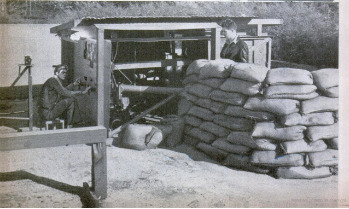

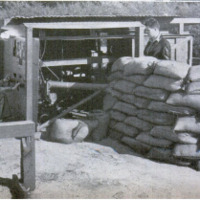

PROTECTED against deadly

explosions by a wall of

sandbags and heavy tim-

bers, two young California In-

stitute of Technology scientists

feed explosive gases under pres-

sure into the motor of a rocket.

~ At the touch of a button,

a leaping spark ignites the

mixture, and with a roar,

a sheet of flame, and a

cloud of smoke, the gases

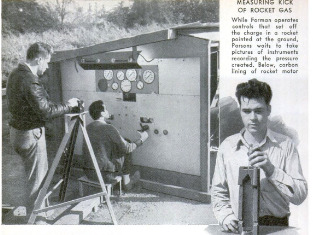

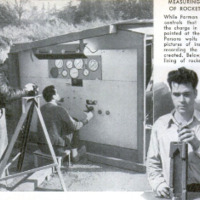

go into action. Operating

a camera, one of the re-

searchers’ photographs a

battery of instrument dials

that reveal such vital facts

as the thrust of the motor

and the weight and pres-

sure of the gases surging

through pipes from me-

tered chambers,

But the rocket itself, in-

stead of soaring into the

heavens, remains rooted

on the ground, since it is

anchored in place and

pointed earthward. For

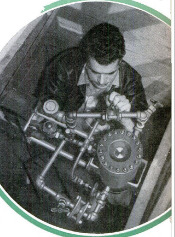

Edward S. Forman and

John W. Parsons, the

California rocket re-

searchers, are mainly

interested for the pres-

ent in studying the ac-

tion of various fuels for

stratosphere - stabbing

rocket ships, and the ef-

fect of their intense

heat on various types of

nozzles.

This question of rock-

et-motor nozzles is one

of the major problems

now facing rocket ex-

perimenters, who are

‘constantly devising new

improvements and new methods to

take the rocket out of the realm of

fantasy and into the field of practi-

cal use. Booster motors to assist

rocket take-off, gyroscopes to guide

flights along straight paths, water-

cooled nozzles, range finders to re-

cord altitudes and speeds, automatic

parachutes that return the rockets safely to |

earth—these are some of the devices that |

are now being tested and brought to per-

pala SoS nA wlll

dozen fronts.

North of Roswell, N. M, for instance,

rockets wobble skyward from a sixty-foot |

tower, and then straighten out into a true |

vertical path, soaring up two miles into the

air at a speed of more than 700 miles an

hour. At the top of their flight, they hang in |

air a split second, then tumble over and float |

gently down to earth as their parachutes

automatically belly out. The gyroscopic

mechanism that straightens out the initial |

take-off wabble is a development engineered

by Dr. Robert H. Goddard, rocket pioneer.

Stabilizing vanes attached to the rocket are |

automatically controlled by the gases of the

exhaust stream, moving the rocket back into

line when it wanders ten degrees away from

a vertical path.

But actually how close is rocket science to

practical exploration of the stratosphere at

an altitude of, say, fifty miles? Studies at

the California Institute of Technology lead

investigators to believe that with the ex-

haust velocity of 7,000 feet a second ob-

tained by Goddard's rockets, powder rockets

could now be built capable of rising 100,000

feet. In fact, under some conditions, they

believe a gas-propelled, eighty-five pound

rocket, exhausting its burned fuel through

a nozzle at the rate of 12,000 feet a second,

could rise under power to an altitude of fifty

‘miles, and then continue, “coasting,” straight

up for another 175 miles.

For more than three decades scientists

have sought ways to explore the atmosphere

at great heights. Today their thoughts are

turning to levels where rockets would fly

through a vacuum, and celestial observa-

tions might be made without interference

from city lights, haze, clouds, or air mole-

cules of lower altitudes. One well-known

astronomer even went 50 far as to suggest

the possibility of a complete astronomical

observatory, raised a thousand miles above

the earth by one set of rocket motors, and

maintained at that level by another.

Of more immediate practical application

is the proposal that rockets take over the

duties of heavy artillery in laying down a

concentrated bombardment of an intensity

not reached even with dive-bombing air-

planes and the latest type of field and rail-

way guns. Major James R. Randolph, of the

U.S. Army Ordnance Reserve, recently de-

clared that rockets could easily equal the

performances of long-range guns firing

shells as far as seventy miles.

‘These long-range cannon fire a projectile

eight inches in diameter. “Instead of firing

shots of moderate caliber at long intervals,”

said Major Randolph, “a rocket plant could

fire the equivalent of twenty-four-inch shells

as fast as desired.”

Projectiles envisaged by this officer would

weigh four tons. Thousands of them, set off

simultaneously or in volleys, might lay

down in a few minutes a withering barrage

that present artillery could equal only over

a long period of time.

Armor-piercing rockets, Randolph further

proposed, could be carried by submarines,

while on land, the rocket shells could be

transported in ordinary motor trucks bear-

ing no resemblance to artillery weapons now

easily identified by enemy planes.

-

Autore secondario

-

Robert E. Martin (article writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1940-09

-

pagine

-

108-110

-

Diritti

-

Public domain

-

Archived by

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)