-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Bombers or battleships

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Bombers or battleships

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

WITH waves of swift bombing

planes casting their winged

shadows over seas long ruled

by battleships, modern air power is of-

fering a new threat to naval supremacy.

Meanwhile we find ourselves embarked on

an unprecedented program of warcraft

construction, and the question of how ef-

fectively our latest ships can meet this

menace from the skies renews a long-

standing controversy between advocates

of air forces and sea forces.

Here is a composite answer as given

by Admiral Harold R. Stark, Chief of

Naval Operations; Rear Admiral A. B.

Cook, head of the Navy's Bureau of

Aeronautics; and other top-flight Army

and Navy officers who ought to know, if

anyone does, just what planes and ships

can do to each other:

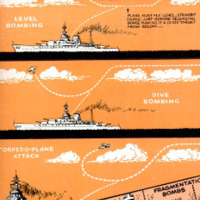

Three types of aircraft menace war-

ships, each in a specialized way—horizontal

bombers, dive bombers, and torpedo planes.

And each has its advantages and drawbacks.

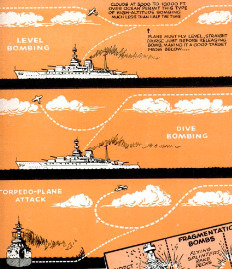

‘Horizontal bombers attack their targets

from relatively high altitudes, aiming their

missiles with a precision bomb sight. The

size of these large multiple-engine craft

gives them great cruising radius and bomb-

carrying capacity. Flying miles high makes

them comparatively safe from a warship’s

antiaircraft fire.

But all is not on the side of the bombers

crew, by any means. For safety in altitude,

they pay in loss of bombing accuracy.

Viewed from 5,000 or 10,000 feet, even the

biggest warship makes a pretty small gray

speck upon the blue ocean. If they descend

to improve their chances of hitting it, their

own chances of getting hit by its five-inch

antiaircraft guns rise in exactly the same

proportion.

And here is a little-known fact. More

than half the time, clouds over the ocean

prohibit bombing from above 10,000 feet.

For days on end, unfavor-

able weather may keep the

“ceiling” much lower.

Even worse, a horizontal

bomber suffers from one

incurable weakness, owing

to its method of bomb sight-

ing. Just before dropping a

bomb, for a period variously

estimated from fifteen sec-

onds to more than a minute,

it must maintain an abso-

lutely fixed course and speed. This delights

antiaircraft gunners.

Dive bombers use entirely different tac-

tics. Power-diving almost vertically upon

their target at more than 400 miles an hour,

they release bombs at such low altitudes

that the projectiles can scarcely miss. In

this type of bombing, there need be no

elaborate corrections for altitude, wind, and

the speed and direction of the target. Only

the simplest sort of sight need be used; the

pilot virtually aims the bomb by aiming

the plane. A favorite stratagem is to “dive

out of the sun,” 8o that its glare blinds gun-

ners below.

But the dive bombers’ very style of at-

tack means flying down the barrels of all

the antiaircraft ordnance that can be

trained upon them. They run the gantlet,

not only of the big hand-loaded guns, but

also of the shorter-range multiple pom-

poms or “machine cannon” that throw a

continuous hail of small explosive shells,

much as a machine gun fires bullets. Then,

100, the terrific strain of

‘pulling the planes out of

their fast dives re-

quires bombers of this

type to be small ma-

chines. Because of their

diminutive size, their

capacity to carry bombs

is limited Likewise,

their curtailed weight

of fuel tethers them

within a short range of

their base. An admiral

who gives a respectful-

Iy wide berth to a “bee-

hive” of shore-based

dive bombers need have

little fear for his ships.

‘There remains the tor-

pedo plane. To launch

the torpedo slung be-

neath its fuselags, it

heads toward the broadside of

the vessel, skimming close to the

water. A likely hit requires a

dangerously close approach, un-

der heavy fire from the ship.

Shells striking the sea ahead of

the plane throw up great geysers

of water, which will shear off the

wings of an air raider plowing

into them at high speed.

Aircraft carriers of a fleet give

it additional and powerful pro-

tection against all forms of air

attack. Fighter planes sent aloft

by the hundred from carriers

may be able to destroy or ward

off the raiders before they reach

bombing positions.

But what happens if a warship

does have the bad luck to get

hit with an air bomb? Whether

minor damage results, or Davy

Jones's locker receives a new-

comer, depends both upon the

type of bomb used, and the class of ship.

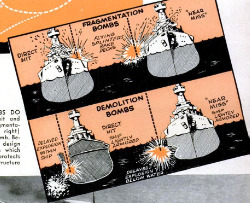

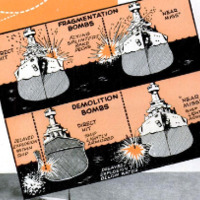

“Fragmentation” bombs inflict casualties

among exposed personnel. Fused to explode

instantaneously, they hurl deadly fragments

of steel in all directions. If they miss a ship

and hit the water near-by, they still det-

onate in time to rake the deck with their

splinters. Because of their light weight—

thirty pounds or less—airplanes can carry

large quantities of them. For the same

reason, they effect little or no structural

damage upon a ship.

“Demolition” bombs, on the contrary, are

all that the name implies. They range in

weight from fifty to 2,000 pounds. Often

they are fitted with delay-action fuses, so

that they burst after penetrating the target

or the surface of the water. So adapted, a

bomb of this type acts in the same way as

a depth charge to destroy a thin-skinned

submarine. Spotted from the air while it

is submerged, an undersea craft is helpless

to fire back or, because of its limited speed,

to maneuver to dodge bombs. At the sur-

face, it is almost as vulnerable. In fact, re-

ports indicate that air bombers are almost

as effective antisubmarine weapons as the

sub chasers of the last war.

Destroyers and other small warcraft, too,

can be sent to the bottom by a direct hit

from a heavy demolition bomb. Their pro-

tection lies in their limited size as targets,

and their ability to throw off a bomber's

aim by fast, zigzag maneuvering.

Bigger ships, though better targets, have

more in their favor. Even an amateur math-

ematician will realize that, when you add

to a ship's size, the deck area increases only

as the square while the displacement and

therefore the weight of armor that can be

carried increases as the cube. This ex-

plains why great battleships can be armored

far more effectively than smaller craft

against air bombs.

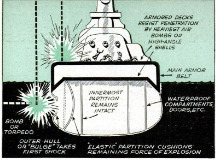

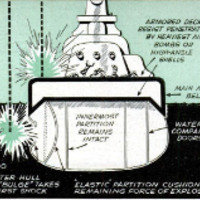

Massive horizontal decks of armor plate,

placed as near as possible to the water line

to conserve stability, supplement the “belt”

or side armor of modern capital ships. Orig-

inally intended to protect the magazine and

other vital parts deep in the hull from high-

angle shellfire, this deck armor now serves

the added purpose of warding of air bombs.

In the newly launched 35,000-ton U.S. bat-

tleships Washington and North Carolina, it

is reported to attain the extraordinary total

thickness of ten inches. Even a 2,000-pound

demolition bomb, formidable as it. sounds,

shatters against such armor like an egg

dropped on a concrete pavement.

Special demolition bombs could be built

that would penetrate deck armor, but their

tremendous weight of steel would allow only

a small explosive charge. For gravity to

give the bombs sufficient velocity to pierce

the armor, planes would have to loose them

from an altitude corresponding to the 10,000-

foot-high trajectory of shells fired from

guns, reducing the chances of a direct hit.

‘And nothing else would do, for an armor.

plercing bomb dropping in the water near

a ship would carry too little explosive to

harm It.

In contrast, a standard thin-skinned dem-

olition bomb acts like a mine if it explodes

under water alongside a vessel. Multiple,

water-tight compartments are the battle-

ship's defense against

such a “near miss,”

and a damage-control

crew springs into ac-

tion to stop leaks, pump

out flooded compart-

ments, and restore the

ship to an even keel.

How to protect a big

ship's superstructure

against direct hits by

demolition bombs, which

may cripple if not sink

it, remains a major

problem confronting

the world’s admiralties.

One solution proposed

by naval architects en-

visions warships of the

future completely cov-

ered with turtleback

armor, with virtually

all the upper works re-

moved, and only the

muzzles of big guns

protruding from the carapace of steel! What-

ever form it may eventually take, however,

the majestic battleship remains the most

invulnerable of all surface craft—as has

been proved in actual bombing experiments

upon old, scrapped, and radio-controlled U.S.

capital ships. One had to be sent to the

bottom by shellfire after repeated bomb ex-

plosions failed to sink it. 5

And now, how do all the factors of air

power versus sea power add up? Evi-

dently the balance is close—unless the scales

are tipped violently, one way or the other,

by the particular mission of the sea or air

forces.

If shore-based bombers embark on a long-

distance raid against an enemy fleet, fuel

load will limit their bomb capacity. Lack of

escort planes, incapable of flying so far, will

Jeave them open to attack by defending

planes, as well as by antiaircraft fire. Loss

of valuable bombers is likely to outweigh

the military value of any damage they

might do.

CONVERSELY, an admiral would be

courting disaster by using his fleet to

force a landing, or cover an evacuation of

troops, within easy range of a powerful ene-

my air base. Only an emergency would jus-

tify the hazard. It is a comforting thought

that an invader’ fleet would face the same

warm reception from our own army's flying-

fortress bombers.

But this country’s grand stategy differs

as much from that of Europe as the vast

oceans that lap our shores contrast with

land-locked European waters. For our de-

fense, we picture

our Navy as engaging any enemy fleet far

out on the high seas, where land-based

planes play no part in the combat. It would

be the carrier planes of the two flcets that

would fight it out in the air, while the sur-

face craft joined battle below. So far as

carrier-based dive bombers or torpedo planes

could shake off attackers, and damage op-

posing warships, so much would that con-

tribute—even if not decisively—to the ulti-

mate outcome of the engagement. But it

would be joint action by sea and air that

counted, whether it was an air bomb or a

shell that finished off a hostile vessel.

So, from our own viewpoint, “air power”

and “sea power” become merged into one.

‘Taken separately, neither one completely as-

sures our security. Reénforcing each other,

they constitute a mighty defense team to

safeguard America.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Alden P. Armagnac (writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1940-10

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

52-56, 228

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly. v. 137. n. 4. 1940

Popular Science Monthly. v. 137. n. 4. 1940