-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Industry goes to war

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Industry goes to war

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

AMERICAN industry is mobilizing its

men and machines to fill the big-

gest and most important order it

has ever received. Time-to-go-to-

work whistles that have been silent for

years are blowing again. New plants are

being built. Government arsenals are work-

ing three shifts, six days a week. By next

spring our manufacturing machine will

have been shifted into high to turn out the

airplanes, guns, fighting ships, and muni-

tions we must have to make us safe against

any form of aggression.

It took Hitlerized Germany seven years

of peacetime “total” mobilization to get

ready for the current war. Never in all

history had there been anything that

equaled that awe-inspiring national effort.

It was a peacetime mobilization that

missed no one. Industry was controlled

by the placing of “must” orders and

the allotment of raw materials, and

the salaries of its executives ‘were

limited by government regulation.

Labor, which worked seventy hours a

week, was controlled by the outlawing

of unions, prohibition against chang-

ing jobs without official approval, and

outright conscription. Capital was con-

trolled by compulsory investment of

profits in no-interest government se-

curities or in unprofitable enterprises.

It was strictly an “or else” program.

Orders were backed up with threats

of heavy fines, economic ruin or, for

the really obdurate, a concentration

camp or even a firing squad. Those

seven years cost the German people

their political and economic freedom

and the equivalent of 40,000,000,000

American dollars, but they gave the

Nazis the most nightmarish war-mak-

ing machine the world has ever seen.

In an effort to assure the safety of

the United States in a world which

gives every indication of remaining

rough, tough, and dangerous for a

good many years to come, Congress in

the course of its present session has

appropriated over $10,000,000,000 in

the form of cash and of contract authoriza=

tions, for national defense.

Those appropriations will be spent) to

order 14,394 airplanes for the Army /and

Navy, and so make a start on a program

which calls for the production of 25,000

planes a year by July 1942; to procure com=

plete armament and equipment for a/mod-

ern, highly mechanized army of 1,200,000

men, and the hard-to-get-in-a-hurry items of

armament and equipment for an additional

800,000 men; to start the building of ap-

proximately 200 additional fighting ships

which will give us a Navy powerful enough

to control the Atlantic and the Pagifie at|

the same time; and to provide new national-

defense construction and manufagturing

facilities, including the expansion of sHip-

yards and the building of thirty-one ord-

nance plants far enough away from our

Coasts to be beyond the range of air attack.

Congress has supplied the necessary

billions. Transforming those billions into

bombers and fighters, into antiaircraft

canon and field guns, into ships, tanks,

motor trucks, O. D. uniforms, Garand

rifies, undershirts, and the 70,000 or so

other things the fighting services need is

industry's big job.

Hitler, using the dictatorial “entweder

oder’ method of getting things done,

achieved astounding results by handing

Germany's industrial mobilization over

to the rotund, hard-boiled, and able Mar-

shal Hermann Goering and his economic

general staff of impressively uniformed

officials. Uncle Sam, sticking to our demo-

cratic “Let's go, gang!” method of volun-

tary cooperation, is confident of getting

equally satisfactory results by having the

production end of our preparedness pro-

gram guided by industrial experts who work

for the Government for nothing a year and

who think, act, and look very much like the

thousands of other doing-all-right Ameri-

cans you can see any week day on New

York's lower Broadway, Chicago’s LaSalle

Street, Detroit's Cadillac Square, or at the

Rotary Club luncheon in Springfield—

Massachusetts or Illinois.

To get those experts on the job, late in

May President Roosevelt used the powers

of the National Defense Act of 1916 to re-

vive the World War Advisory Commission

to the Council of National Defense, which

had been dormant for almost twenty years.

The Commission acts as a cobrdinating

agency between the Government depart-

ments which have to procure national-de-

fense material for the armed services and

the industries which will have to provide it.

‘When he made his appointments to the

key positions on the National Defense Ad-

visory Commission, President Roosevelt

gave the world a convincing demonstration

of the fact that the United States still is a

country where the really big jobs go to men

who have proved that they have what it

takes to handle them.

William S. Knudsen, automobile assembly-

line wizard left his big job as president

of General Motors to cobrdinate the produc-

tion of defense material, break bottle-

necks, and be the Commission's all-around

trouble-shooter. Edward S. Stettinius, Jr. re-

signed his $100,000-a-year position as chair-

man of the board of the U. S. Steel to become

the Commission's procurer of raw materials. Sid-

ney Hillman, who is in charge of codrdinating

labor and of training workers for the defense in-

dustries, has been president of the Amalgamated

Clothing Workers of America ever since the or-

ganization of that union in 1914.

The other members of the commission are

Ralph Budd, the president of the Chicago, Bur-

lington and Quincy Railroad, in charge of cobrdi-

nating all our transportation facilities; Chester

C. Davis, a member of the Federal Reserve Board,

who is responsible for accommodating agricul

tural problems to the defense program; Leon

Henderson, of the Securities and Exchange Com-

mission, in charge of the statistical study o

prices; and Miss Harriet Elliott, dean of women

at the University of North Carolina, whose

duties include the protection of consumers

And trying to keep down the cost of living.

None of the commissioners receive salaries,

but the Government pays their expenses. All

of them are assisted by staffs of executives

and expert advisers.

While the Commission has no formal exec-

utive authority, it reports directly to the

President and under the National Defense

Act he President has all the authority he

needs to drive through the defense pro-

grams authority to establish priorities

which would give Government orders the

right of way whether or not business men

liked it, and authority to place compulsory

orders. | So the Advisory Commission has

iron fists, although it has worn, and is likely

to continue to wear, velvet gloves over them

in its dealings with industry.

Its methods are well illustrated by its

Handing of the question of priorities. Sup-

pose, fOr example, that Greene & Browne,

who are in the toy business, decide to bring

out a new-design kiddie car, and place their

order fOr the machine tools necessary to

manufacture it. A week or two later Black

& White sign a contract to make—let’s say

— antitank-gun parts. They must have spe-

cially designed machine tools to make them,

and they can’t get those tools in a hurry

because Greene & Browne got their order

in first. Black & White go to the Advisory

Commission with their troubles. Antitank

guns being, in the present unhappy state of

world, affairs, considerably more essential

to the nation’s welfare than kiddie cars, the

comimission could ask the President to paste

a priority label on Black & White's order,

and Greene & Browne would have to wait

and Whistle for their tools. But the Com-

mission doesn’t do that. Instead, one of its

repres ntatives calls on Greene & Browne

and explains the situation. Greene and

Browne go into a huddle and, being patriotic

citizens, come out of it with an offer to hold

over their new kiddie car until next year so

that Black & White can get those antitank-

gun parts into production.

The Commission calls that the preference,

or voluntary priority, system of procure-

ment, and up to date it has worked so well

that there has been no need to enforce legal

priorities in order to get results.

The way in which Ralph

Budd, the Commission’s

transportation codrdinator,

deals with the railroads pro-

vides another example

of the “Let's go, gang!”

nethod of getting things

done without fuss or bad feel-

ing. Noticing that on June 1

there were almost 164,000

box and open-top cars—

slightly over ten percent of

the railroads’ freight-carrying

rolling stock—awaiting re-

pairs, and anticipating heavy

defense-industry traffic this fall, he wrote (as

one railroader to another) to the president of

the Associatione of American Railroads sug-

gesting that to, make Sure that they would

be able to do their part of the defense job

the lines should redftice the proportion of

“bad orders” to less than six percent by

October 1. The October figures aren't avail-

able yet, but it’s a dollars-to-doughnuts bet

that When they are released they will show

that the number of cars needing repairs

has been reduced below the requested figure.

ITS ability to make good use of the per-

sonal approach is one of the Advisory Com-

mission’s biggest assets. The automobile

manufacturer who gets a letter from it ask-

ing him to go into the making of airplane

cannon knows that it didn’t come from some

War Department brass hat, but from Big

Bill Knudsen, the fellow who knows all

about assembly lines. The union official

‘who is asked to solve the labor problems of

a shell-making plant knows that he isn't

dealing with some office-holding theorist

but with Sid Hillman, a veteran labor man.

Gaudy uniforms and high-sounding titles

may impress people in some countries, but

American business men like to do business

with men who wear the same sort of

clothes they do and who speak their lan-

guage. That's one of the reasons why, even

if some day we should get into a big war,

our industrial effort will be guided by

civilians.

One of the reasons for bringing Knudsen

to Washington was that he is a famous

breaker of production bottlenecks. The

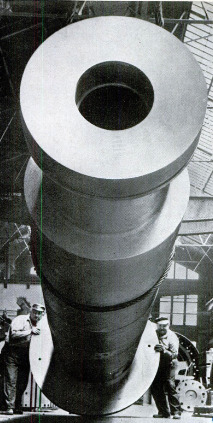

first bottleneck he attempted to break on

his new job was in the machine-tool indus-

try. Machine tools are necessary for the

production of every weapon from a .30

caliber rifle to a sixteen-inch harbor-defense

gun. Shells can't be made without turning

lathes, and the armor plate for a battleship

can't be worked without huge planers and

millers. A serious shortage of machine tools

would block our defense campaign before it

ever got started.

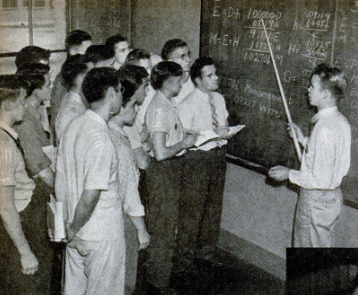

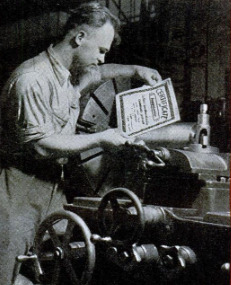

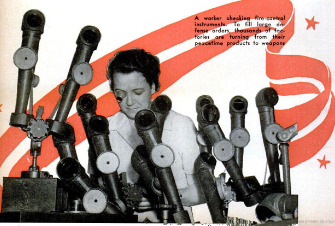

The firms in the industry offered the

Government 100-percent cooperation, indi-

vidually and through the National Machine

Tool Builders Association. They already

had cracked one of their own potential

bottlenecks by starting to train workers

both in their plants and in codperation with

vocational schools. Priorities weren't neces-

sary. All that was needed was to tell the

tool makers what the Government wanted

first. They put their facilities as completely

at the nation’s service as if war had been

declared. They codperated with the Com-

mission's and the Army Ordnance Depart-

ment's experts in designing a machine

“Whe doubles the production of rifle bar-

rels, and in the development of a simple

single-purpose lathe which can, if neces-

sary, be operated by a woman and which

can be produced by others than expert ma-

chine-tool makers. The work of the tool-

making industry hasn't been spectacular,

and some of it of necessity has been slow,

but it has been highly effective.

Many people have feared that a shortage

of some critical raw material might seriously

handicap our rearmament. That is possible,

but the danger seems remote. We have

nearly all of the materials we need, and

have them in quantities which are prac-

tically inexhaustible. For some years Gov-

ernment agencies have been building up

stock ples of materials which we can't

produce and which we might have trouble

in getting in an emergency. Just how large

those stock piles have grown no one outside

the Government knows, but it Is no secret

that since Stettinius was appointed to the

National Defense Advisory Commission's

procurement Job he and his staff have dis-

played very considerable ingenuity in add-

ing to them.

Most of our rubber comes from the Malay

Peninsula and the East Indies, and our sup-

ply might be cut off if Japan went on the

warpath against us. That would have been

fatal twenty years ago, but it is much less

serious today. Several American manufac-

turers are ready to undertake the large-

scale production of synthetic rubber made

from petroleum.

Ordinary gasoline, the lifeblood of mech-

anized warfare, presents no problem. Our

supply of 100-octane gas, of Which our ex-

panded air forces will use tremendous quan-

titles, is being conserved by means of an

embargo, and adequate reserves are being

stored in safe places.

The chemical industry is coSperating

whole-heartedly in the national effort, even

to the extent of its members exchanging

closely guarded secret formulas with their

competitors!

EVERY bit as vital to our national defense

as the man with the gun are the men be-

hind the man with the gun. The number of

workers necessary to arm and equip each sol-

dier and keep him supplied with the food, am-

‘munition, clothing and all the other things

he needs in war have increased in propor-

tion with the increased mechanization of

warfare. In the World War we needed six

workers for every soldier. At the outbreak

of the present war German military authori-

ties estimated that they were going to need

eighteen workers for each soldier!

Rearmament is different from war be-

cause it doesn’t have to make good the in-

credible loss and waste of

war, 50 we won't need so

high a ratio of men in

overalls to men in uni-

forms. Industrialists figure

that during the coming

year our defense program

won't demand more than

a tenth of our industrial

productiveness.

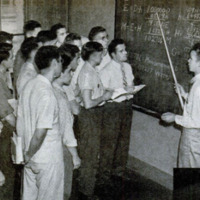

After investigating our

probable manpower needs,

Sidney Hillman says that

the reservoir of our 5,500,-

000 unemployed workers

will take care of most of

our labor problems of the

near future. Many of

these men are unskilled,

but many others of them

were skilled, and the Gov-

ernment is’ giving them

the opportunity to take

refresher courses, at

W.P.A. wages, to bring

back the skill they lost

during their years of rust-

ing. Large numbers of

unemployed youths are

being trained for the de-

fense trades. The Gov-

ernment also is cobperat-

Ing with employers in |

providing on-the-job train-

ing for employed workers

Who want to qualify for

better jobs, and in train-

ing apprentices. The

United States Employ-

ment Service, which has

‘over 1,500 offices, wil help

in bringing the right

worker and the right job

together, and in overcom-

ing labor shortages in in-

dividual trades and in par-

ticular localities.

‘We have the money, we

have the materials, we

have the manufacturing

facilities, and we have the

men. What are we doing

with them? Are we get-

ting anywhere with or

rearmament job?

Perhaps our progress i

increasing our air force is

disappointing to optimists

who expected to‘see those

50,000 airplanes President

Roosevelt mentioned fly-

Ing before this winter. it

isn't disappointing to the

Then in the industry who

knew the tremendous amount of make-

ready work which would have to be

done to increase production from a few

hundred planes and engines a month

to 50,000 planes and 125000 engines a

year. Most of the planes on order now are

training planes—they are needed first.

Knudsen is confident that the industry, in

addition to filling its British contracts, will be

able to give us 18,000 Army and 7,000 Navy

planes by July 1942. It will take at least

another two years for it to reach the 50,000-

a-year production level.

Most of the 10,340 large and small manu-

facturing plants—located in forty-five states

—which have been approved by the Army

and Navy have received orders and are

working on them.

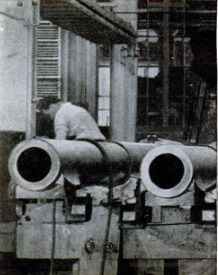

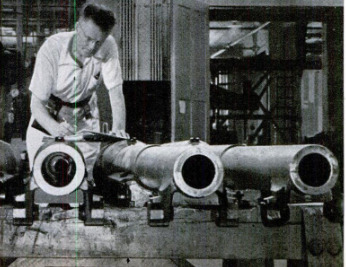

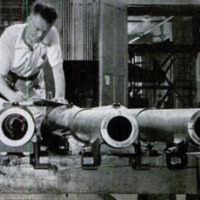

AMERICAN industry is literally beating

Plowshares into swords. Manufacturers |

of agricultural implements are producing gun

carriages and combat wagons; producers of

lathes for making wooden shooting-gallery

ducks are turning out lathes for army

shoes; church pipe-organ makers supply |

wooden frameworks for military saddles.

Makers of printing presses are producing |

the recoil mechanisms for 155-millimeter

howitzers; manufacturers of vacuum clean-

ers are making gas masks, and specialists

in adding machines are turning out shell

fuses. Factories that formerly created toy

soldiers and miniature trains are develop- |

ing gears and canteens; troops in the field |

will sleep under mosquito netting furnished

by firms that make ladies’ underwear.

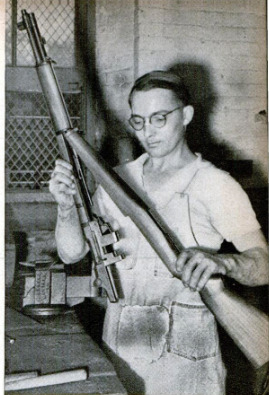

Weapons are rolling off the production

lines in Government arsenals and privately

owned factories. The Springfield Arsenal is

making 1,560 Garand rifles a_ week; two

years ago its production was 150 a week.

One manufacturing plant is turning out an

average of six light tanks a day.

Work has been started on a Govern-

ment-owned, Du Pont-operated powder

plant at Charlestown, Ind. Next spring it

will start producing 20,000 pounds of

powder a day. In 1917 the contract for our

first powder plant wasn't signed until after

we had been at war for seven months. A

‘seamless-tubing manufacturer in Pennsyl-

‘vania is making steady deliveries on a $25,-

000,000 airplane-bomb order.

‘Within the next month or so the Quarter-

‘master Corps will take delivery of 5,000,000

yards of serge which will make 1500,000

©. D. uniforms, 4,000,000 yards of heavy

‘woolen cloth which will make 1,000,000 over-

coats, and 1,500,000 yards of worsted shirt-

ing which will make almost 1,000,000 shirts

for fighting men.

‘Work is being rushed on the Navy's com-

at ships now under construction. As soon

as they are off the ways their places will

be taken by other new fighters. The expan-

sion of shipbuilding facilities soon Will be

started, to take care of both naval and

‘merchant-ship construction.

‘From coast to coast the roar and clatter

of machinery and black smoke belching

from factory chimneys are telling the world

that if any emergency arises, America will

not be caught unprepared!

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Arthur Grahame (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1940-11

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

79-84

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly. v. 137, n. 5 1940

Popular Science Monthly. v. 137, n. 5 1940