-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Balloon flights train navy airman

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Balloon flights train navy airman

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

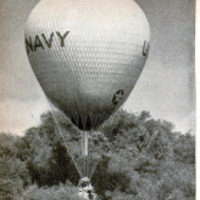

WITH dive bombers and 400-mile-an-

hour fighting planes in the head- |

| lines, few people know that the

drifting free balloon, the earliest of all

aids to aérial warfare, is still an essential

link in America’s defense program. From

the field at Lakehurst, N. J., where the bal-

loon school of the U. S. Navy is entering

its twentieth year, silver-hued gas bags

have traveled a total of more than 25,000

miles in training flights. Because a blimp

with a disabled engine must be handled like

a free balloon, all men in the Navy's lighter-than-air

service begin with a balloon course at the Lakehurst

school.

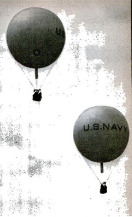

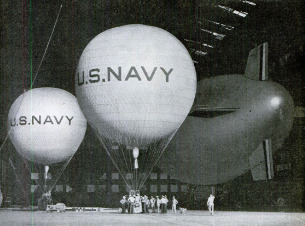

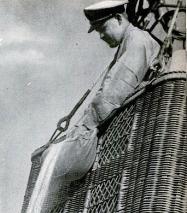

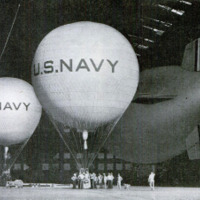

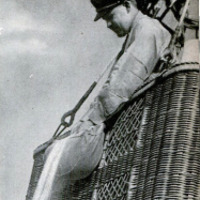

The six 35,000-cubic-foot balloons used in the work

are inflated with helium. As one of them is filled for

a flight, the ground crew adjusts the netting carefully

so the five-foot-square wicker basket is exactly cen-

tered. With as many as four students and an instruc-

tor squeezed into the basket, the ground crew “walks”

the balloon, towering seventy feet in the air, out onto

the field from the hangar in which it was inflated.

Instruments, road maps, a woodsman’s compass, and

carrier pigeons are loaded aboard. Then comes the

start. A shower of sand ballast, a slight upward push

by the ground crew, and the great gas bubble soars

away. So silently does it drift through the sky that

men calling upward from the ground can be heard

distinctly at an altitude of 1,000 feet.

During the first five flights, the student watches

and learns. On each trip, he performs some new task

in connection with navigating the balloon. To rise, he

throws overboard ballast; to descend, he lets out gas

through a valve at the top of the bag. Throughout a

flight, there is a continual small seepage of gas so that

ballast has to be discarded from time to time to keep

afloat. To a balloon, ballast is what fuel is to a plane;

when it is exhausted, the flight must end.

Some years ago, before helium was used

in Navy balloons, Lieutenant Commander

Samuel M. Bailey and two students from

Lakehurst were riding under a hydrogen-

filled gas bag in pitch darkness over the

Alleghenies. For hours, their balloon had

‘een losing lift. At one o'clock in the morn-

ing, Bailey decided to “settle im” for a

landing. The basket was four feet from the

ground when high-tension wires loomed

directly ahead. Bulging with thousands of

cubic feet of explosive hydrogen, the great

bag struck the cables. At the same instant,

both students leaped. The balloon bounced

back and then shot like a cannon ball

toward the sky. By hanging to the valve

rope all the way up, Bailey stopped the

zoom at 8,000 feet and descended unharmed

on a mountaintop farm.

Overnight flights are next to the last

ones made by students at the Lakehurst

school. As a special precaution, the Navy

sends a warning to all air-line pilots to

watch out for the balloons. Two lights, a

steady white one and a flashing red one,

are suspended under the baskets. Both are

battery-run. Because of the more even tem-

perature at night, two bags of ballast will

often carry a balloon through the hours of

darkness. On the other hand, during

one day trip, Lieutenant Commander

R. F. Tyler had to throw out five

bags—150 pounds—of ballast from

an altitude of 500 feet to keep from

being carried to earth by a strong

downdraft over a cool swamp a few

‘miles from Lakehurst.

Solo flights, which end the train-

ing, are never started if the breeze

is blowing faster than fifteen miles

an hour, and all trips begin only

when the winds blow from an east

erly direction carrying the balloons

inland, away from the near-by At-

lantic. With the wind as navigator,

carrying the gas bag in whichever

direction it blows, the Navy balloon

riders are never sure where they

will land. One crew, last year, de-

scended in the middle of a cemetery;

another in brambles six feet high.

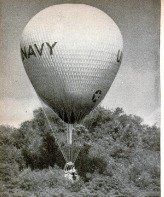

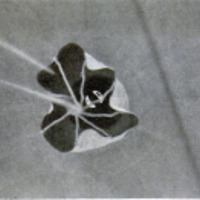

Whenever possible, the landing is

made just beyond woods, So the

trees form a windbreak. Valving out

gas, the pilot brings the basket to

within fifteen feet of the ground.

Then he jerks the ripcord, tearing

out a long panel in the side of the

bag. The gas rushes out, the bag

collapses, and the flight is over.

At the end of every overnight

journey, pigeons are released to

carry back word of the landing lo-

cation, and the bag and basket are

shipped home by freight. During

shorter, daytime trips, a truck fol-

lows the drifting balloon to pick up

the equipment and crew.

The simplest job these Navy

truckmen ever had came at the end

of one training flight last fall. The

balloon took off in the morning and,

drifting west on a sea breeze, disap-

peared. Late in the afternoon, it re-

appeared over the field, riding a

wind that blew in the opposite direc-

tion at a higher level, and descended

for a landing only a few hundred

yards from its starting point!

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Robert E. Martin (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1940-11

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

86-89

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly. v. 137, n. 5 1940

Popular Science Monthly. v. 137, n. 5 1940

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-01 12.55.02.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-01 12.55.02.png Ekran Resmi 2022-02-01 12.55.09.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-01 12.55.09.png Ekran Resmi 2022-02-01 12.55.16.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-01 12.55.16.png Ekran Resmi 2022-02-01 12.55.23.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-01 12.55.23.png Ekran Resmi 2022-02-01 12.55.30.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-01 12.55.30.png Ekran Resmi 2022-02-01 12.55.35.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-01 12.55.35.png Ekran Resmi 2022-02-01 12.55.41.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-01 12.55.41.png Ekran Resmi 2022-02-01 12.55.46.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-01 12.55.46.png Ekran Resmi 2022-02-01 12.55.55.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-01 12.55.55.png Ekran Resmi 2022-02-01 12.56.01.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-01 12.56.01.png