-

Titolo

-

He invented the world's deadliest rifle

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

He invented the world's deadliest rifle

-

extracted text

-

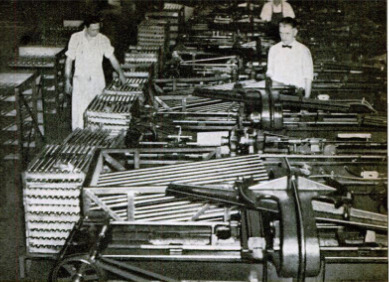

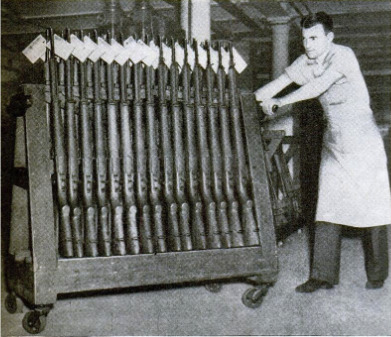

THE United States Government is lay-

ing a $15,000,000 bet that the new Gar-

and semiautomatic rifle is the deadliest

firearm ever invented. At the great,

sprawling Springfield, Mass, Armory orig-

inally established by George Washington,

Garand guns by the thousands are whizzing

off the production lines, while outside,

swarms of workmen rush through the con-

struction of a vast addition to the plant.

Reams of publicity have carried the news

of this rifle to practically every wide-awake

U. S. citizen. But what about the man be-

hind this particular gun? Who is this Gar-

and, and what is he like? How did he hap-

pen to invent the weapon that will make

every American doughboy a one-man ma-

chine-gun nest?

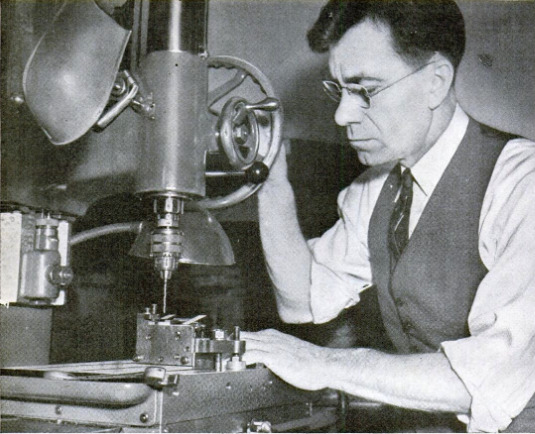

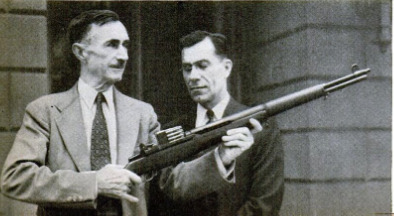

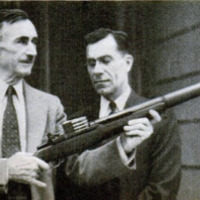

Alert, athletic, square-jawed—that was

my first impression of John C. Garand when

I walked into his Springfield Armory office

a few weeks ago. As you talk to him, you

notice that he pronounces certain words

with a soft French-Canadian accent—a relic

of his earliest years on the farm where he

was born, twenty miles from Montreal. He

was seventh in a family of fourteen chil-

dren. His mother died before

he was eight years old and

the family moved south to

Jewett City, Conn. Here, at

twelve, an age when most

children are still in grade

school, young Garand started

work as a floor sweeper and

bobbin boy in a New England

textile mill.

Machinery had always at-

tracted him. Even today,

Garand’s idea of an exciting

night's reading is to settle

down in an armchair with a

pile of machine-shop maga-

zines beside him. During the

short rest periods, while the

bobbins were filling up, the

boy used to haunt the end of

the plant where the textile

mechanisms were repaired.

The foreman noticed him,

took a liking to him, and let

him pick up extra pennies

scouring down rough places

on spindles with a piece of

building brick. A year after

he came to the mill, Garand

was a boy inventor with a

patent of his own. He had

designed a new type of jack

screw.

As soon as he began mak-

ing money, Garand started

saving toward a rifle. With |

one of his brothers, he used

to spend evening after eve-

ning poring over the gun.

pages of a mail-order cata-

logue, debating the merits of

the different firearms. Final-

ly, the boys pooled their re-

sources and sent off a money

order for a Winchester .32-20.

When it arrived, with a blue,

shiny barrel and smelling of

fine oil, they discovered it

had such a range that they

couldn’t shoot it without en-

dangering cattle and farmers

for miles around.

It was Garand's fertile

brain that solved the diffi-

culty. Obtaining a bent heavy

metal pipe, the boys lugged

it to a little hillock in the

middle of a field. There they

propped it up so that one end

formed a bull's-eye and the |

other pointed skyward. At

200 yards, the boys drove

their bullets into the open

mouth of the pipe. The right-

angle curve sent the lead

streaking toward the strato-

sphere. However, its ear-

splitting “zing!” resounded

over the countryside and

farmers, who were convinced

a bullet had just missed their

ears, came dashing up in bug-

gies to register emphatic

complaints. It usually took a

long argument and a couple

of demonstrations before they

were satisfied.

By the time he was eight-

een, Garand was a full-

fledged machinist at the tex-

tile mill. As a side line, one

summer, he and his brother

ran a shooting gallery at

Norwich, Conn. That was a

lot like a boy with a sweet

tooth managing a candy

store. Their enthusiasm for

target practice ate up most

of the profits.

Not long afterwards, young

Garand landed a job in a

Rhode Island tool factory and

moved to Providence. There

the speed bug bit him and

he took up motor-cycle rac-

ing. An engine of his own de-

sign carried him to victory at

various New England tracks.

Less dangerous, but still giv-

ing the thrill of speed and

balance, was his next interest

—fancy skating on ice. That

occupied his leisure for sev-

eral winters. He would still

like to whirl and spin on skates, but he

doesn’t have time to practice. In spite of |

such varied hobbies, he always kept coming

back to firearms. They formed the center

of his interest, :

In the early days of the World War, Gar- |

and came to New York, working in a microm- |

eter plant in lower Manhattan. Saturdays |

invariably found him alighting from the

subway at Coney Island with a target shoot-

er’s light in his eye. He was star patron of

all the galleries along the boardwalk. Wages

were good, and he shot to his heart’s con-

tent. When he moved from one gallery to

another, a queue of onlookers trailed be-

hind. One Saturday, when he was finding

out about rifles by using Coney Island as a

laboratory, he shot at every target there.

By nightfall, he had set an all-time high for

himself, not only in score but in expense as

well. He had spent $100 at the galleries in

a single day!

Luckily for his bank balance, he discov-

ered a gallery near Times Square, about this

time, where the proprietor would let him |

shoot free. Firing a rifle from the hip so ac-

curately that he could hit a swinging target

seven times on a single swing, he always

attracted a crowd that overflowed onto

the sidewalk and kept the cash register

ringing’ at the gun counter.

During this period, when Garand was rune

ning the World War a close second in boom-

ing the stock of ammunition makers, he

was taking correspondence courses, study-

ing nights to complete a formal education

that had stopped when he was twelve. One

evening, before he sat down to his lessons,

he read in a newspaper that the Government.

was having difficulty finding a satisfactory

machine gun. He couldn't see why there

should be any problem about that, so he sat

down and designed a machine gun of his

own. Folding up his drawings, he slipped

them in an envelope and addressed it to the

Naval Board, in Washington, D. C.

That act switched Garand onto the main

track of his life work. It gave point and di-

rection to his consuming interest in guns,

In due time, a letter came back from the

Naval Board. The experts were sufficiently

interested in his drawings to invite him to

come to Washington for a conference. The

upshot of that

meeting was an offer to turn Garand loose

in a room at the Bureau of Standards and

let him prepare a working model of his gun.

The salary was just half what he was receiv-

ing as a skilled machinist. But he jumped at

the chance.

For eighteen months, Garand buried him-

self in the room set aside for him. At the

end of that time, his gun was finished. But

so was the World War, and the demand for

machine guns was at a standstill. However,

the U. S. Army had become interested in

developing a light, semiautomatic rifle, a

sort of compromise between a machine gun

and a Springfield rifle. Garand moved to

the Armory in Massachusetts and tackled

the job.

That was twenty-one years ago. Ever

since, the struggle to make this radically

new weapon simple enough, strong enough,

and light enough, has continued. These

three problems were in the back of Garand's

mind night and day—when he was work-

ing, lying in bed, playing table tennis or bad-

minton or horseshoes. Often he came down

to the Armory on week-ends and in the quiet

of the great brick buildings wrestled with

the toughest riddle of all, cutting weight to

a minimum.

There were many times when Garand

was positive the weight requirement set by

the Army could never be reached. Eventual-

ly, by saving an ounce here and an ounce

there, without sacrificing strength, he at-

tained the goal. Most of the weight elim-

ination was accomplished by reducing the

number of parts. For example, one spring

in the hammer mechanism now does the

work that originally required five springs.

That mechanical short cut, alone, clipped a

whole pound from the weight of the gun.

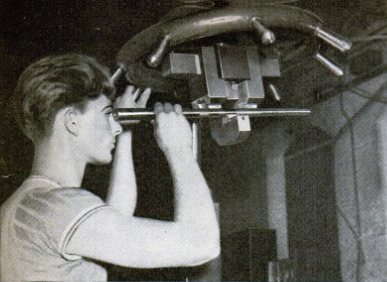

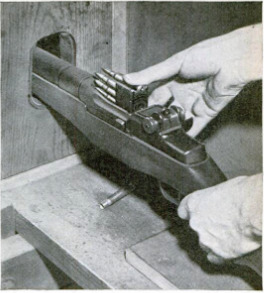

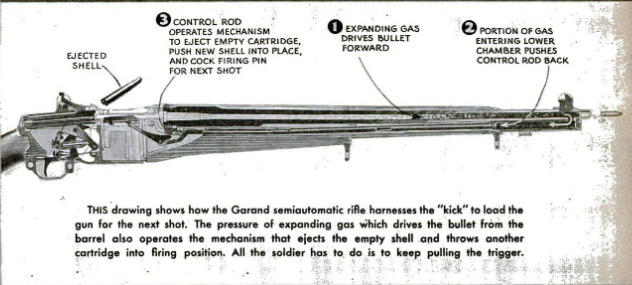

Gas pressure produced by the discharge of

the cartridge automatically ejects the shell

and cocks the gun, so all the operator has

to do is pull the trigger. In other words,

Garand has put the “kick” to work and by

so doing has given American soldiers the

best high-speed firearm on earth.

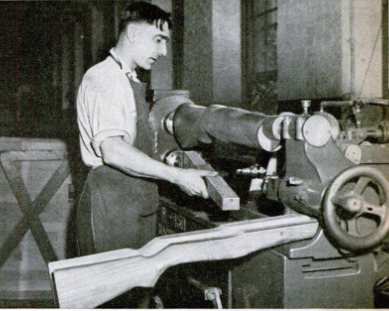

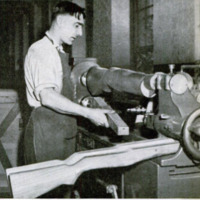

Along the road to this goal, model after

model was designed and worked out with

infinite care, only to be rejected after gruel-

ing tests. Nearly a dozen kinds of gun steel

were tried, and the rear sight alone was re-

designed fifty times. The present Garand gun

combines the best features of half a dozen

discarded designs. All during these years,

other inventors were bringing forth ideas in

competition with the rifle Garand was mak-

ing. His weapon won out over approximate-

ly fifty different models which were sug-

gested or submitted to Army experts.

In those last hectic days when the Arm-

ory was rushing through a batch of the new

guns for large-scale tests, the workmen

labored in two shifts, night and day. Gar-

and worked both shifts, sleeping when he

could. Then came the most strenuous tests

ordnance experts could devise. The gun was

fired almost continuously, far beyond the

limits of ordinary use. It was soaked in

water and thrown in mud. It was even

placed in a sand-blast machine for hours to

see if any of the quartz grains would pene-

trate the mechanism. The rifle passed these

torture tests with flying colors.

Garand has turned down tempting offers

from a commercial company and a foreign

government in order to give the United

States exclusive rights to manufacture his

rifle, For the price of one destroyer, the

whole U. S. Army can be equipped with

the superguns.

This, then, is the story of the man be-

hind the Garand rifle—the story of a former

motor-cycle racer, crack shot, boy inventor,

and toolmaker who, without benefit of a

formal education or an engineering degree,

made firearms history. His two decades of

concentrated application have produced a

weapon which promises to be of outstand-

ing importance in American defense.

-

Autore secondario

-

Edwin Teale (article writer)

-

John J. Garand (inventor)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1940-12

-

pagine

-

68-71, 235-236

-

Diritti

-

Public domain

-

Archived by

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.15.01.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.15.01.png Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.15.08.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.15.08.png Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.15.14.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.15.14.png Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.15.21.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.15.21.png Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.15.26.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.15.26.png Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.15.32.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.15.32.png Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.15.39.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.15.39.png Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.15.44.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.15.44.png Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.15.51.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.15.51.png Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.15.57.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.15.57.png