-

Titolo

-

Mobilizing materials

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Mobilizing materials

-

extracted text

-

TELEPHONE bell rang in the office of Edward R. Stettinius,

A Jr., chief of the National Defense Advisory Commission's

materials division. It was the Chinese Embassy calling.

A sizable quantity of tungsten had just become available in Indo-

China. Would the United States be interested?

It most certainly would. Three calls by Stettinius brought

quick results. The Reconstruction Finance Corporation would

supply funds for the purchase. The Procurement Division of the

Treasury would instruct one of its agents to do the buying. The

Maritime Commission would arrange shipment. Next day, the

tungsten was aboard an American ship, on its way to the U.S. A.

Why should high Government officials concern themselves

about a load of tungsten, instead of leaving it to the regular

channels of commerce? ‘The answer is that U.S. mines yield

less than a quarter of the tungsten that we need for armor-

piercing bullets, lamp filaments, and tools. Therefore the Army

and Navy class it among fourteen “strategic” materials vital

for defense and currently obtained from abroad.

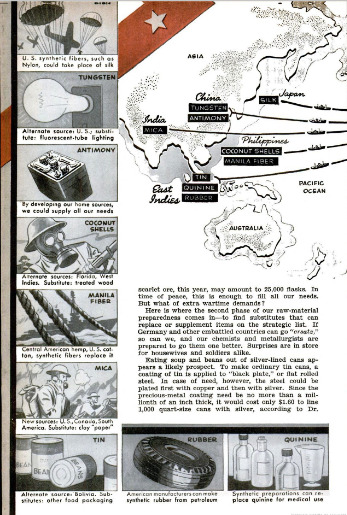

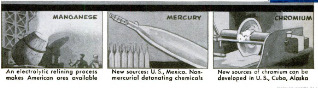

Other strategic materials include manganese, indispensable

for purifying steel; rubber, for tires; chromium, for armor plate

and high-speed cutting tools; tin for food cans, solder, and

bearings; silk for parachutes and powder bags; coconut shells

for the charcoal filters in gas masks. Mercury for fulminate

detonators, antimony metal for storage-battery plates, manila

fiber for ropes and cordage, mica for electrical insulation—all

these, and more, have been checked as “musts” on Uncle Sam's

shopping list.

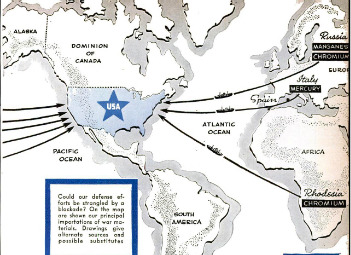

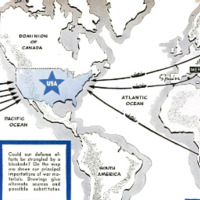

If a war blockade caught us without them, America’s mighty

war machine might never get going. Trucks and gun carriages

couldn't move, without bearings. Artillery shells without det-

onators to explode them would be no more potent than cannon

balls. After tools available at the start of hostilities wore out,

our prized Garand semiautomatic rifle would be impossible to

manufacture. As Tom M. Girdler, prominent steel maker, puts

it, “Down in Kentucky, in deep underground vaults, we have

stored away a great pile of gold. The time might come when

we would gladly give all of that gold for a pile of desperately

needed manganese or chromium.”

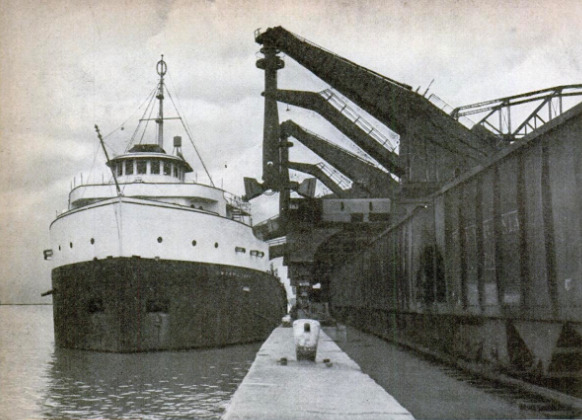

So we're taking no chances. A three-point Government pro-

gram, now in full swing, is fast making the United States proof

against blockade by any combination of hostile naval powers.

First comes the obviously sensible step of locating and exploiting

key supplies nearer home. Dangerously vulnerable is the overseas

trade route that brings us tin and rubber from British Malaya a: 1

the East Indies. So plans are well advanced to use Bolivian tin ore,

by erecting smelters in the United States. Largely for lack of

cheap fuel, Bolivia has no tin smelters, and has been sending the

ore to England for refining. As for rubber, U.S. Department of

Agriculture experts are making a $500,000 survey in Brazil, locat-

ing favorable sites for establishing rubber plantations.

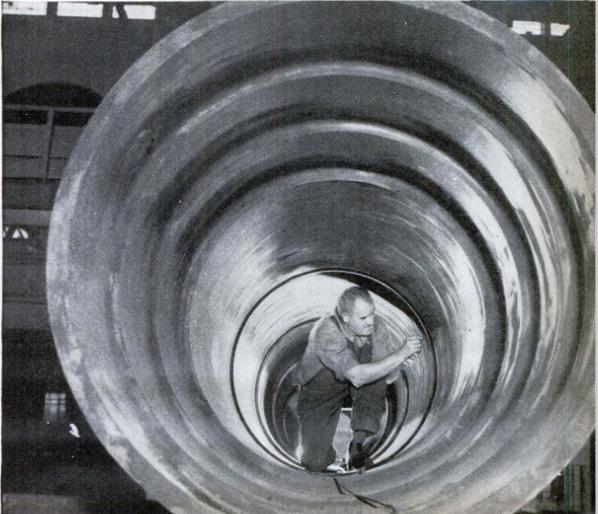

Widespread deposits of low-grade manganese in the United

States and Cuba, long undeveloped, are now being honeycombed

with mine shafts. Through a new electrolytic process, invented by

Prof. Colin G. Fink of Columbia University, the ore can be purified

to rival that of Russia and the African Gold Coast.

Soaring prices of Spanish and Italian mercury, to as much as

$200 for a seventy-five-pound flask, are reopening abandoned mines

in California and Washington. National production from the

scarlet ore, this year, may amount to 25,000 flasks. In

time of peace, this is enough to fill all our needs.

But what of extra wartime demands?

Here is where the second phase of our raw-material

preparedness comes in—to find substitutes that can

replace or supplement items on the strategic list. If

Germany and other embattled countries can go “ersatz,”

so can we, and our chemists and metallurgists are

prepared to go them one better. Surprises are in store

for housewives and soldiers alike.

Eating soup and beans out of silver-lined cans ap-

pears a likely prospect. To make ordinary tin cans, a

coating of tin is applied to “black plate,” or flat rolled

steel. In case of need, however, the steel could be

plated first with copper and then with silver. Since the

precious-metal coating need be no more than a mil-

lionth of an inch thick, it would cost only $1.60 to line

1,000 quart-size cans with silver, according to Dr.

Alexander Goetz of the California Institute of Technology. An alter-

nate proposal suggests substituting bags of Pliofilm, a new synthetic

material, for cans.

Parachutes made of Nylon, the Du Pont fiber made from coal, air,

and water, have been tried out experimentally by the U.S. Army

Air Corps and found to function perfectly. They may help to solve

the problem of our dependence upon Japan for silk, of which standard

‘chutes are fashioned.

Fulminate of mercury, highly sensitive to the slightest shock, has

a new rival for use in the detonators of shells and bombs. The

substitute, a chemical called lead azide, keeps better and contains

no mercury, so the liquid metal may soon be crossed off the roster

of strategic materials. Other substitutes have been found for mercuric

chemicals in less widely known uses—making blue printing ink,

dental rubber, and barnacle-repelling paint for ships’ bottoms.

Automobile tires of synthetic rubber, long talked about, now are

being marketed in the United States. Instead of making it from coal,

as Germany does, American chemists start with petroleum. Thus, mili-

itary vehicles may soon be rolling into battle on tires made from

the same raw material that provides fuel for their carburetors.

An $80,000,000 program for expanding experimental synthetic-

rubber factories into big mass-production plants has already been

initiated, the National Defense Advisory Commission reports.

But it takes precious months to develop mines and to get new

factories into production. In a national emergency, could we do

it in time? To tide us over that critical period while war in-

dustries are getting into high gear, the third and most im-

mediately important part of our strategic-material program is

being put into effect.

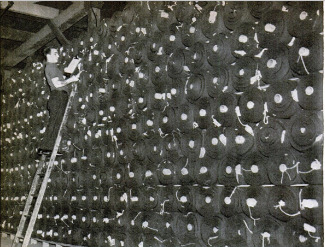

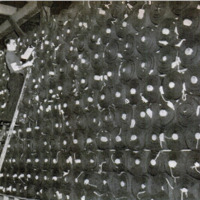

Gigantic piles of imported war metals and other supplies

are being laid in by Government agencies, and stored on military

reservations, “for fire use only.” Kept intact unless war comes,

they would then be thrown into the balance, while new sources

were catching up with military demands.

Beginning last year, the United States has been stocking up

heavily on thirty-seven strategic and near-strategic materials.

Its fast-growing reserve of manganese, intended to fill all war-

time needs for a year, results from orders placed in India, Africa,

Chile, and at home. The Anaconda Copper Company has con-

tracted to furnish 80,000 tons a year for three years from its

Emma mine in Montana. A rising pile of chromium results from

orders placed first in Turkey and Alaska. Wherever possible,

contracts have been awarded to foster development of United

States and Western Hemisphere sources; at the same time,

urgent needs must often be filled from far-away countries. Huge

international cartels have contracted to furnish us nearly a

year's supply of vitally im |

portant rubber and tin. |

Odd items appear in some

of the orders—for instance, |

tons of quinine, to ward off

disease if our soldiers op- |

erate in the tropics. Quartz

crystals will be needed to

keep radio transmitters on |

the right frequency; in an |

emergency, they could be |

flown by plane from Brazil, |

but the United States is |

forehandedly laying in |

plenty for storage.

Novel commercial ar- |

rangements have been con- |

cluded and are under ne-

gotiation. We wanted 85,000 |

tons of British rubber. The

English wanted 600,000 |

bales of American cotton. |

It was a deal. Despite war |

difficulties, a large propor- |

tion of the rubber has been |

delivered. At this writing,

the United States and Great

Britain are working out a

plan to store 200,000,000 to

300,000,000 pounds of Brit-

ish wool in this country, |

subject to purchase for the

U.S. Army in case of war.

Then it would be made

into Army overcoats, and

‘blankets.

So far the story has been

of America’s weaknesses,

and their cure. With these

headaches off our mind, we

can settle back and com-

fortably reflect on our

strong points. No other

country in the world can

boast such an enviable assortment of natural resources at home.

Food, most essential of all raw materials in war or peace, isn't

one of our defense worries. We raise more than we eat of almost

every important foodstuff from apricots to wheat. We won't have

to choose between cannons and butter—we can have all we want

of both. If war should come, mild rationing of sugar and coffee

might be necessary. But our ability to import large quantities of

both commodities from Latin-American countries, bordering on

the Caribbean, probably would avert even that inconvenience.

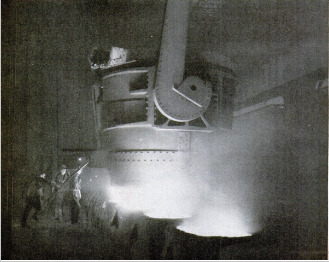

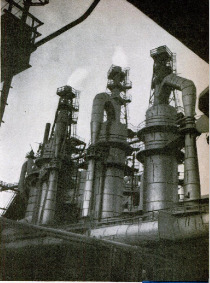

Steel is the great essential of armament, and iron and coal

are the principal raw materials used in steel-making. We have

enormous reserves of both, and can easily mine enough to meet

even the tremendous demands of all-out warfare.

‘War in the air, the use of oil as fuel for modern fighting ships,

and mechanized warfare on land have combined to make petroleum

an imperative military necessity. Our resources, greatest in the

world, will fill all needs for oil and leave an ample supply for mak-

ing synthetic products. Large stocks of the comparatively new

100-octane aviation gasoline are being accumulated and stored for

Army and Navy air forces.

Besides these principal sinews of war, we have, or are sure

of being able to obtain, virtually all the rest—copper, lead,

nitrates, sulphur, magnesium, cotton, lumber, to mention only a

few. With newly acquired reserves of the ones we have lacked,

we are perfecting our armament on the economic front—where

undeclared wars may be waged without firing a shot, and where

battles may be decided before they are fought.

A tank car of petroleum may be worth a good many bombs,

and a few shiploads of iron ore may prove as valuable as a

whole squadron of planes, to a country less fortunately endowed

with raw materials than our own. Conversely, the nation that

has them in abundance is in a commanding position to bid for

international advantages, and to wage war or put a brake on it.

The United States embargoes shipments of aviation gasoline

outside the Western Hemisphere—ostensibly to conserve our

supply, but incidentally denying it to militant Japan. We lend

China $25,000,000, to be repaid by future shipments of tungsten.

As Japan gobbles up French Indo-China, America cuts off vital

Japanese supplies of scrap iron for warships and armament.

To make Brazil independent of Europe for heavy steel, U.S.

experts and a $20,000,000 loan will help build the largest steel

plant in South America—freezing out Krupp, the great German

armament concern, and other foreign interests.

In tense, dramatic moves upon the chessboard of international

politics, raw materials will continue to make big news. Even in

peace, America’s wealth in them plays a powerful strategic

role. And in war, you can strike an enemy as effectively with a

lump of manganese as with a bayonet.

-

Autore secondario

-

Arthur Grahame (article writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1940-12

-

pagine

-

73-80

-

Diritti

-

Public domain

-

Archived by

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.31.33.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.31.33.png Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.31.45.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.31.45.png Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.31.55.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.31.55.png Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.32.27.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.32.27.png Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.32.40.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.32.40.png Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.32.48.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.32.48.png Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.32.56.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.32.56.png Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.33.03.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.33.03.png Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.33.09.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-02-02 11.33.09.png