-

Titolo

-

How our army planes are to be judged

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: The wings of victory

-

Subtitle: This is the yardstick against which our army planes are to be judged

-

extracted text

-

RMCHAIR AVIATORS, high-altitude ra-

dio commentators, and literary strate-

gists have, in the last few months, managed

to throw the public mind into a dither of

doubt as to the value of our military air-

craft. Their chief weapon has been compari-

son—the quotation of figures which have

made some of our planes appear third-rate.

‘The public, untrained to weigh evidence in

this highly technical field, has been given the

wholly unwarranted impression that Uncle

Sam is sending his air crews out to meet

the enemy in inferior ships.

The industry producing aircraft has been

too busy to refute these comments; the

ARMCHAIR AVIATORS, high-altitude ra-

dio commentators, and literary strate-

gists have, in the last few months, managed

to throw the public mind into a dither of

doubt as to the value of our military air-

craft. Their chief weapon has been compari-

son—the quotation of figures which have

made some of our planes appear third-rate.

The public, untrained to weigh evidence in

this highly technical field, has been given the

wholly unwarranted impression that Uncle

Sam is sending his air crews out to meet

the enemy in inferior ships.

The industry producing aircraft has been

too busy to refute these comments; the

Army has rightly declined to reply to them.

Both prefer to allow the military record

of the nation’s aircraft to make its own

answer. Unfortunately, however, the very

information which would vindicate our mili-

tary seers, designers, and builders happens

to be of highly confidential nature. For the

time being it is more valuable to the enemy

than it is in the hands of the average lay-

man. Perhaps it would be better to present

the average citizen with his own yardstick

against which he can measure the success

or failure of the aircraft that are being

produced for his protection.

The fate of the world is being decided in

the field of military conflict. The outcome

of this conflict is, in a large measure, being

decided by air power. The success of an air

arm depends upon how well its aircraft are

fitted to perform the tasks set for them by

the pattern the conflict has taken. This fit-

ness depends on how shrewdly our military

planners guessed many months before.

In a large measure, the Axis has lost a

phase of this war, despite a measure of ter-

ritorial success, owing to what was prob-

ably the worst guess in history.

The Luftwaffe, originally, was a short-

range army co-operation machine geared

to act as artillery over a front 50 to 150

miles deep. It rolled over Poland like a tidal

wave. If it had kept going, it might have

caught Russia with its air-power down.

Instead, the tidal wave turned and swept

over an aeronautically unprepared France.

At the end of this collapse, the Luftwaffe

ran into the first correct guess on the side

of the United Nations—the Hawker Hurri-

canes and the Supermarine Spitfires.

In 1935, Sir Hugh Dowding, Chief Air

Marshal, called for open bids on a fast,

rocket-climbing, eight-gun ship, capable of

outspeeding and outmaneuvering anything

on wings. Its rate of fire would make it

poison to anything capable of operating

over a longer range than its own. Virtually

everything was sacrificed for speed, climb,

and maneuverability and fire power. At the

evacuation of Dunkirk and the bitter battle

for Britain, the Luftwaffe measured up to

the specifically ordered job only eight

inches to the R.A.F.'s 12 on the ultimate

scale of comparison. Swarms of aircraft

invaded the island, only to be driven off.

The early Junkers JU-87, the Dornier DO-17

and other models that carried the brunt of

the early blitz were short-range aircraft.

Their mechanical advantages had to be

pared considerably to get them over Eng-

land and the thousands of wrecked aircraft

that littered the English countryside were

evidence of the stupidity of the move. Goer-

ing had, in the homely words of the late

“Paddy” Finucane, “tried to eat soup with

a knife.”

How good have our guesses been? How

well are we prepared to fight the type of

war that is unfolding, with equipment that

had to be planned two or more years ago?

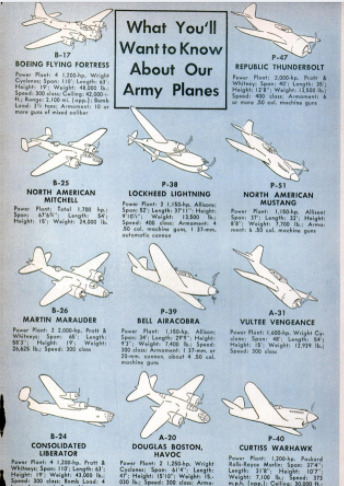

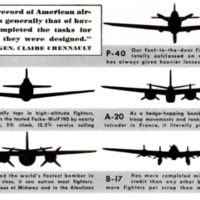

Ten or possibly 11 United States types

now in production will carry the weight of

our part in the current conflict.

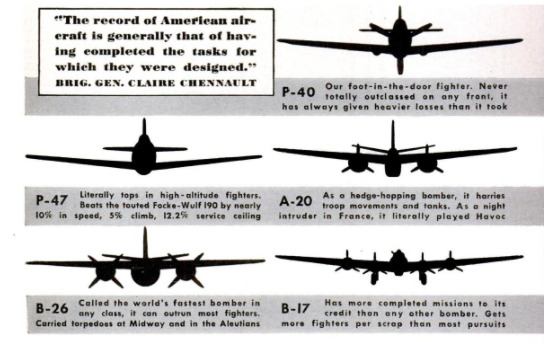

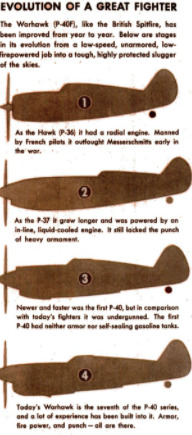

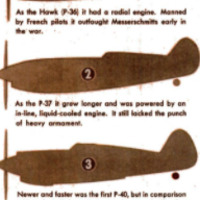

Probably the most discussed and

maligned of our types has been the

Curtiss P-40. This ship has, at times,

been called the worst and the best

guess of the entire war. Its design

was laid down when no one knew

quite what the war was going to turn

out to be. The type has undergone

seven alterations and modifications,

each one a distinct improvement. It

evolved as the work horse among

United Nations single-seaters.

Tactically, it is an advance-guard

airplane. It is assigned to new opera-

tions where all-around performance

is needed plus the ability to “take it.”

P-40’s have been active in every Unit-

ed Nations front in this war where

land-based aircraft have operated.

They are selected because they are

tough and can be thrown against any-

thing the enemy has. Even if they

are outperformed, they are “beefy”

enough structurally to “duck for home,”

bringing with them what special infor-

mation is necessary to dictate the spe-

cialized aircraft or action needed to re-

place them. They are easy to maintain.

Simple, rugged design and structure

have produced an airplane that is easy

to service and repair. Major structural

replacements, needed only when the

ship is badly battered, can be accom-

plished with the most elementary tools.

The airframe requires virtually no at-

tention. It is sealed and bonded against

the ravages of sand, snow, and tropical

rain. They can be staked outdoors for

months on end. A mechanic who serv-

iced the type in the Philippines, where

airplanes are known to disintegrate

outdoors, said that all the P-40 needed

was gas, oil, and a few kind words and

it would keep running forever.

Justification for the type need only

be read in the final box score wherever

the P-40 went. In the Philippines, a

handful of them cost Japan over five ships

for each P-40 in combat. Here they acted

as fighters, scouts, photo ships, and even

bombers. During the last days on Bataan,

MacArthur's mechanics stuck four P-40s

together out of wrecks and spare parts,

rigged them as bombers, and sent them out

to sink 30,000 tons of shipping in Subic Bay.

In China, their score was 3.9 to one, in

Australia, 3.1. In Russia they were the only

craft capable of clearing the way for the

Stormoviks, while in the Libyan desert they

tackled tanks and bombed troop emplace-

ments. Wherever the task assigned to it

paralleled the original purpose of the fight-

er, the U. S. defense problem, it made every-

thing else it encountered look ridiculous.

The war in the desert belonged to U.S.

types, for at those distances and under

those conditions they were at home.

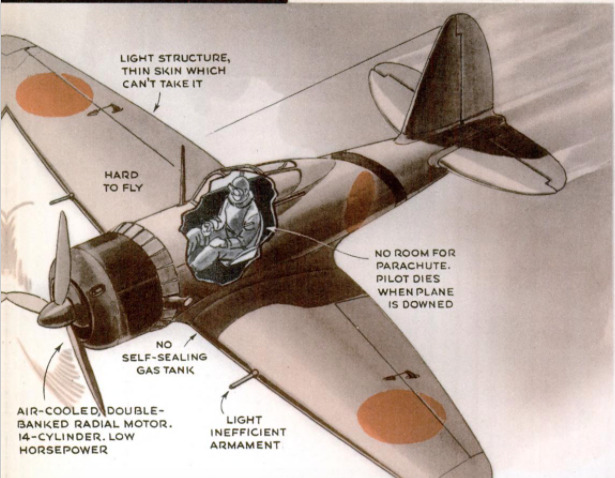

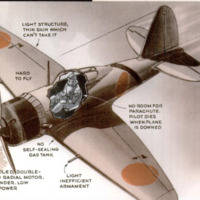

Probably the prize dumb comparison in

this war is that of the former naval pilot

who compared the P-40 with the Jap Zero.

The over-all box score should have told the

story—3.52 Japanese lost for every P-40.

In turn and rate of climb, certainly the Zero

had an ample edge, but it paid plenty for

the privilege. To begin with, the Zero

weighs 4,750 pounds wringing wet. It car-

ries neither armor nor a self-sealing tank.

Its fuselage, from the cockpit back, is cov-

ered in a gauge of dural thinner than any

rolled in the U.S. It had only a fraction

of the number of instruments carried by the

U.S. pilots, the flier wore no parachute,

the general structural factor of safety was

about 2.5 to 1, differing from the 12-to-1

characteristic of our craft. Annodizing, to

protect the ships from ravages of the

weather, is virtually unknown. The Zeros

are frequently unpainted and only a “dim-

mer” coat keeps the sun from making them

a long-range target.

Those who would like our men to fly this

kind of a winged coffin are reminded of one

thing. At the outset of the war, a rumor

was current that the “heroic” Jap pilots

would crash-dive their airplanes rather

than allow them to be captured in examin-

able shape. This was a figment of the im-

agination. The truth of the matter was that

the Zero was so frail, that any mishap in

landing would practically roll the craft up

into a ball.

The Curtiss-Wright Corporation finally |

sank the “magnificent Zero” myth once and |

for all when they stripped thirteen hundred

pounds of weight out of a P-40—spare

guns, self-sealing tanks, Instruments and |

the like. They reduced its armament and |

load to that of the Zero without impairing

the P-40's inherent structural strength.

The experimental airplane, thus stripped,

carrying a 180-pound pilot with his para-

chute—and, toting a wing loading in excess

of the Zero's 20 pound per square foot, out-

climbed, outturned, outmaneuvered and |

outfought the Zero on every one of the 11

basic categories of performance laid down |

by General Chennault and the Flying Tigers

in China. |

The question arises, why are these air--

planes fought carrying these heavy Wing

loads? The answer can be found in the

basic military philosophies of the two na-

tions. To the Japanese, the victory belongs

to some abstract personage and the sol-

dier. His individual existence means noth- |

ing. Providing for a better than even

chance for the pilot is unheard of. Techni-

cal experts who have examined the wreck-

age of the Zero state that its frailty made

simply flying this craft an act of desperate

heroism. Extreme gust acceleration found

under thunderheads or similar meteorologi-

cal conditions have been known to shake

the Zero apart. We as a nation believe that

the victory belongs to the individuals who

make up the nation, the air crews among

them. The victory is of little value to them

if they do not survive to enjoy it. We

choose to enhance our pilots’ chance of sur-

vival by every mechanical means at our dis-

posal, leaving heroism to the individual

choice. We simply do not elect to pay for

that kind of performance with the safety of

our flight crews.

The ultimate justification for our philos-

ophy of sacrificing the edge of performance

for a margin of safety lies in the fact that

Japanese Sentoki 001, the successor to the

Zero, carries self-sealing tanks, heavier

general structure, etc. Despite 300 more

horsepower, it 1s inferior to the original

Zero on climb and turn. While human life

is a small consideration to the Japanese

high command, the number of men lost

through structural weakness of the craft

prompted a change. The Jap Air Staff

guessed wrong—the change admits it.

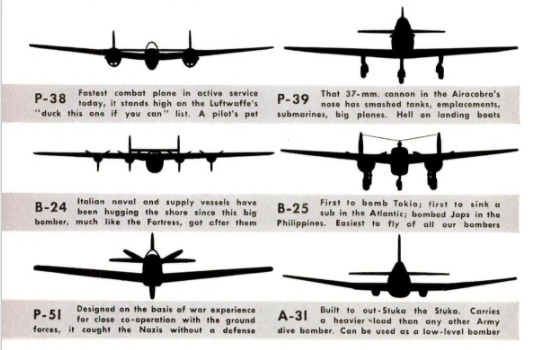

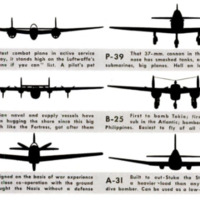

The next in line for literary back-stab-

Ding is the P-39, the Bell Airacobra. From

its inception, this child of scorn and wiz-

ardry had a lot of people disliking it. The

pilot sat in front of the engine, the power

was delivered in a U line down from the

drive shaft, under the cockpit floor, and up

to the propeller. Here it met the basic as-

sumption of the Alracobra, the 87-mm.

cannon, supported by two synchronized .50

caliber guns and four .30's firing free out-

side the propeller arc. Changes may have

Zero, carries self-sealing tanks, heavier

general structure, etc. Despite 300 more

horsepower, it is inferior to the original

Zero on climb and turn. While human life

is a small consideration to the Japanese

high command, the number of men lost

through structural weakness of the craft

prompted a change. The Jap Air Staff

guessed wrong—the change admits it.

The next in line for literary back-stab-

bing is the P-39, the Bell Airacobra. From

its inception, this child of scorn and wiz-

ardry had a lot of people disliking it. The

pilot sat in front of the engine, the power

was delivered in a U line down from the

drive shaft, under the cockpit floor, and up

to the propeller. Here it met the basic as-

sumption of the Airacobra, the 37-mm.

cannon, supported by two synchronized .50

caliber guns and four .30’s firing free out-

side the propeller arc. Changes may have

been made in the general armament setup,

but the theory of building an airplane be-

hind a gun had proved out. The Airacobra

is murder on anything that gets in front

of it.

The radical idea of putting the engine,

the heaviest single piece of equipment in

the whole airplane, smack on the center of

lift and load was looked at with suspicion

by orthodox designers and air tacticians.

Off-line power delivery looked uncertain,

unreliable, and an invitation to maintenance

trouble. Nevertheless, the guess was that

somewhere an airplane would be needed

that could blast its way into and out of

formations of anything that flies. Larry

Bell started with the idea that the best

place to put an antiaircraft gun was on an

airplane. The most important single ad-

vantage of the P-39 general design is that

the size, rate of fire or shell velocity of the

forward-firing gun can be altered as the

requirements of war change, without major

modification of the type.

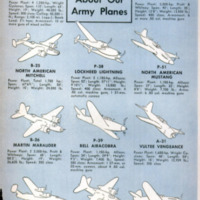

The P-38 was our original bid for high-

altitude strength. A radical design, it is

singularly maneuverable for a twin-engined

ship. The basic disadvantage of most twin-

engined fighters is their inability to make

short-radius turns. Having two parallel

lines of thrust and two similar torque al-

lowances to make, the craft must “bend”

two force lines in order to turn. This makes

the banking harder, just as it is more diffi-

cult to turn sharply with a car than it is

with a motorcycle. The Lightning gets

away from this problem in a measure by

turning the propellers in opposite directions.

Thus each engine counters the other's

torque, eliminating dynamic allowances for

this turning tendency such as wing warping,

and off setting the

vertical fins which cut down speed. It also,

in effect, makes the airplane practically

torqueless, therefore, more maneuverable.

Putting the pilot and armament in a sep-

arate nacelle or streamlined pod in the cen-

ter of the wing offers several advantages.

In the first place, the accuracy of fire from

the four .50 caliber machine guns and sin-

gle 37-mm. cannon is enhanced by the fact

that they are mot mounted over or in the

same line with any vibrating power plant.

Grouped as closely together as they are,

the guns’ fire pattern is concentrated over

a small area and has the effect of a combi-

nation meat grinder and buzz saw when it

gets the range for even a short burst. The

small nacelle can be sealed airtight and su-

percharged without the mechanical diffi-

culty encountered in the ordinary full-

fuselage designs. This makes it one of the

top high-altitude jobs of all time.

The P-51 is our latest baby, so good that

even the British have gotten enthusiastic

about it. It is a change-of-pace airplane.

The hell that the U.S.-built Flying For-

tresses have raised in the “out of sight”

fighting levels have forced the Axis to build

such monstrosities as the Focke-Wulf 190,

the new Messerschmitt 210, and the like.

Suddenly the Mustang arrives, capable of

making great speed within a shadow of the

ground. Only the luckiest kind of a shot can

bring one down.

The human ear can pick up the sound

of this low-flying infant only when it is

overhead. One of the forerunners of the

Dieppe raid was said to be a lone P-51 that

picked itself a deep, rolling Channel swell

and, skidding all the way across the Chan-

nel in its trough, hopped over the sea wall,

flew between two buildings, heaved a salvo

of delayed-action bombs into the largest

radio installation on the occupied French

coast, and dashed back before the German

alarm system had a chance to function.

It is a lot harder to get a low-altitude

ship to go fast than one built to operate in

the substratosphere. The thin air in the

higher levels offers little resistance to the

wings, and as long as there is enough sur-

face and enough power, the airplane can

move at quite a clip, simply because there

is little to hold it back.

At the lower levels, while the lifting

characteristic of wings is far more efficient,

the air offers far greater resistance. At

high speeds, it tends to “pile up” just be-

hind the highest point of wing curve, At

speeds approaching 500 m.p.h. on most con-

ventional wing curves, the air actually

breaks its “laminar flow” and lift-destroy-

ing turbulences occur in the boundary layer.

The Mustang is winged with a special air-

foil whose profile permits the smooth flow

of air at all speeds.

Some of the aforementioned critics of

U.S. tactics seized upon the scant early

information on the P-51 to criticize the fact

that it had poor high-altitude performance.

To begin with, the P-51 has no high-altitude

performance--none was built into it. Every

line, provision, and device in the ship was

built for phenomenal speeds at low levels.

An early critic stated that the new German

FW-190 that appeared at about the same

time would probably outrange and outfight

the Mustang if it tried to come up and do

combat at the 190's most efficient level of

22,000 feet.

In the first place, the P-51 would prob.

ably never seek combat with a 100. It is not

built to do that kind of a ob. Secondly, the

P51 could not get to 22,000 feet with any-

ting lesa than & atrato-balloon. Buti

the 190 had the bad judgment to come

down to the lower levels, It would be a

helpless aa a fiah out of water. Consider

the welght side of t. The 100 would be

running around with the welght of an

unused supercharger, oxygen system, the

weight and drag of a thick, high-altitude

Wink, 40 percent of which would be wurplus

at low levels, and its pilot wrapped up in a

toddy-bear sult. 1s engine, geared to pro-

duce ita top power in’ thin air, would be

putting out lows than 60 percent of ita

Power. Compare this flounderer with the

Cocky Kid flying in hin shirt sleeves In a

comfortable low-altitude Job, with only the

thinga he needs urrounding him; his engine

putting out every rev it €an ind n Wing

custom-built to keep him fying at his own

particular level

Ft mate to the Lightning, the P41, Re

publica “Thunderbolt, Is our newest bid for

Bigh-altitude supremacy. Av yet unproved

in’ battle, we have only characteristic com-

parison to check it galnst. Wo know that

type ia needed that can stand and Aght

at high wltitudos, that has range enough to

meet and intercept. high-flying, ov-rango

aircraft, that will have speed and climb to

Spire nnd have one prime virtue missing in |

most high-altitude craft gunpouer. So far, |

10 ship AL any clans or altitude has demon: |

strated the horizontal speed of the Thunder. |

bolt. Ita rato of climb in phenomenal, its |

gunpower burst equal to the Impact of

fve-ton truck at 60 mph. The fact that

tho two Iateat-type fighter crart operate at

opposite levels indicates the Justification of

the former U. 8. theory for the conduct of

war, the change of pace that requires the

enemy to keep a great diversity of equip-

ment in production.

The A Class attack and dive bombers—

are the group that stands between fighters

‘and bombers. We have concentrated on two

such types. The A-20, known as the Douglas

“Boston” in its day-raider conversion and

the Havoc as a night fighter, is basically an

attack bomber. It is bullt to operate at

near pursuit speeds, pack a lot of gun-

power forward and enough maneuverability

to take on any single-seater built, The big

thing that was asked of the A-20 design

was range of speed-— the ability to cruise at

Dear-stalling speed for hours on end, hunt-

ing out troop concentrations, convoys, and

weal spots. Once they are spotted, the

A-20 hauls up its flap, opens the gun, and

punishes the objective with a murderous

fre-cluster forward, baptizes it with bombs

as it goes over, and then dusts it off with

the rear gun as it speeds by.

The Boston's record in daylight sweeps

over the continent is equaled only by the

African record. A thoroughly disorganized,

busted-up troop, supply, or tank movement

is termed Bostonized no matter how the

action happened. The A-20's wide range of

speed and favorable landing characteristics

promoted by an awninglike flap and tri-

cycle landing gear have made the night

version, the Havoc, with double forward-

firing power, ideal for prowling around

German fiying fields in northern France,

wating for some unfortunate bomber to

try to take off. At the precise moment when

the bomber begins to be nir-borne, the

Havoc dives in and gives it a single burst,

frequently causing the ship to explode with

1fe Griiee ctruetive Wad aboard,

The manufacturer's designation for this

type is the DB-7. It is the first one of its

type to be able to out-Stuka the Stuka and

fight anything that came against it.

The other U.S. member of the A class,

other than the Douglas “Dauntless,” which

was borrowed from the Navy as a short-

range stop-gap, is the A-31, the Vultee

Vengeance. Originally programmed for ex-

clusive British production, this design in-

corporates all the virtues of the former

types of single-engined dive bomber, stam-

ina plus good control of diving direction;

and speed, plus enough gun-power for its

own defense.

The original Stuka, the Junkers JU-87 is

an outstanding example of a one-purpose

airplane carried to a great extreme, A

capable dive bomber, it was a dead duck

if caught by anything that could really

fight. The Germans tried to counter this

frank tactical mistake with imitations of

the DB-7—light, twin engined bombers

equipped with diving brakes. While these

were fairly successful, they gave up some

of the essential virtues of the JU-87: eco-

nomical operation, great maneuverability

close to the ground, steep diving angle, and

great variety of dive pattern.

Combining our own U. S. dive-bomber ex-

perience with some of the German ideas

plus the British experiences, the Vengeance

was built. In the first place, the Vengeance

is plentifully armed. Its total gun power is

that of the average single seater. It carries

its bombs internally, permitting at-will

bomb selection and higher speeds. The

average enemy dive bomber carries most of

its missiles externally, and the loads, usu-

ally hung under the wings, must be symmet-

rically released to keep the ship under

good control.

Our two current medium bombers stack

up well against their basic requirements,

and the basic requirements indicate that the

Air Staff were better guessers than average

in this class.

In the B-25, they asked for a medium-

weight bomber that could operate out of

short, unprepared fields under all condi-

tions. It required mid-altitude performance

for middle distances under fire through

hostile country. Therefore, a good part of

the useful load had to be invested in arma-

ment. While the first submarine sinking in

the Atlantic and General Doolittle’s raid on

Tokio may have been spectacular demon-

strations of the B-25's versatility as a com-

bat bomber, General Ralph Royce’s raids on

Japanese emplacements in the Philippines

showed the ship to its best advantage. Slip-

ping into hastily prepared advance bases, so

quickly arranged that the enemy hasn't

found” them yet, Royce punished them

soundly from both low and medium alti-

tudes and was out of range before the yellow

brethren could gather their wits.

This demand for “get up and go” is amply

supplied by the Mitchell, as the type has

been named. In Australia and the Archi-

pelago it has been flown from beaches and

crudely hacked-out fighter-advanced posts.

Its heavy armament allows it to operate

without fighter support and frequently with-

out any advance pursuit co-operation. In

other words, a gang of B-25's is capable of

parking anywhere midway between the

enemy and a supply base and operating as

long as the fuel, ammunition, and supplies

flow in at a tolerable rate.

The Martin Marauder, the B-26, was one

of the most spectacular guesses in air his-

tory. There were some in the Air Force

that would have bet heavy odds that Peyton

Magruder’s overgrown closed-course racer

would wind up a prototype and a number.

Like the bumble bee, one could prove on a

slide rule that it was incapable of taxiing,

much less flying. Magruder, young, lithe,

handsome nonconformist, kicked half of

the accepted theories for bomber construc-

tion out of the window when the Army

asked for a terrifically fast short-range

bomber that could interchange weight for

range at will.

Several basic sketches were presented at

a staff meeting at Martin's. Some were im-

provements on the existing Marylands and

revised Baltimores, others were radical

changes. The most radical was the Ma-

gruder suggestion. Glenn Martin took one

quick look at the B-26 and selected it. Some

wondered if the boss was slipping.

No one, thus far, has doped out a logical

way of attacking the B-26. Hauling nearly

as much armament in a small area as a

heavy bomber, carrying nearly as much

weight as a Fortress (a shorter distance),

most fighter craft would have to work hard

to catch this ship and then might find they

had a bear by the tail. With plenty of guns

forward, top, tail, at its sides, and below,

it resembles the B-17 in the completeness

of its gun-arc coverage.

At Midway and off the Aleutians, they

have been “doubling in brass” as torpedo

planes. The rack for torpedoes has been

built into all existing models. It can serve

interchangeably as heavy-weight, short-

range bomber with its normal tanks; mid-

dle-weight, mid-range bomber with a fair

load; or it can, by installing self-sealing

tanks in as many of its four bomb bays as

needed, haul a bigger torpedo farther than

anything except a submarine or a destroyer.

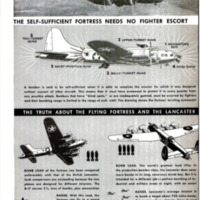

We can stick our chests out the farthest.

in the long-range bomber class. First, our

B-24, the Consolidated Liberator. Having

the intestinal fortitude to adopt a radical

wing curve is something even Japan's des-

perate ministry dared not do. The Davis

wing that mounts its long, tapered span,

permits greater lift from its area than any

other yet devised. There is a lot that can-

not be said now about this wing, but the

fact that the B-24 is the backbone of our

air-freight system indicates that it is the

hottest long-range hauling machine in the

history of transportation. Like the P-40 it

is a foot-in-the-door airplane. Its tricycle

landing gear allows it to get in and out of

places formerly reserved for light, twin-

engined transports of the 9,000-pound class.

Alongside the Hurricane and the Spitfire,

the B-17 will probably remain among the

greatest tactical guesses in history. The

self-sufficient bomber was a pet dream of

General Arnold for a decade. The original

proposition was to build an airplane that

could strike hard or sink a battleship half

way out in the Atlantic, disperse landing

efforts off the bulge of South America, or

hop off the bastions of Hawaii or the sta-

tions in the Philippines to meet an enemy

fleet anywhere in the Pacific. More impor-

tant, it was determined even then that a

bomber, trying to get to a vital area in the

heart of an enemy country, would have to

fight off wave after wave of attackers.

This meant that its penetration was limited

not by the amount of fuel but by the

defensive ammunition it could carry.

Load-hauling, high-climbing aircraft had

been built before, but this ship had a spe-

cific job to do—precision bombing at long

range at high altitude. It could not afford

to have its radius of action limited by the

range of escort aircraft. It had to proceed

to a distant target alone. The U.S. Army

bombsight would permit spot effectiveness

of bombing, so too much weight was not

necessary. This was no pattern-bombing

craft, satisfied to slip in at night and ob-

literate an area; the global war for which

this was built required that it be able to

hit one ship, one block, or one house from

a height out of range of any attacker.

How has the General Staff guessed ? Look

at the pattern of its result in every theater

of war. To begin with, what other nation’s

equipment is serving wherever fighting is

taking place? Obviously, our equipment is

the only group built to fight a global war.

In each class, two types are represented at

least—one “foot-in-the-door” airplane to es-

tablish advanced bases, feel out the enemy

and establish the pattern of action. The

others are the knockout types, the ships to

come in and deal the telling blows.

Our aircraft have shown up as superior

to any, even those of our allies, in one out-

standing general characteristic stamina.

Those who foresaw a global war knew that

aircraft would have to be dispersed to far

places, transferred from one climate to

another, live outdoors for the duration and

frequently be maintained with the simplest

tools or no tools at all.

These are the 11 main types. We will

“probably see many more added before the

conflict is over. Nevertheless, there are

experts who expect to see only modifica-

tions of these less-than-a-dozen in the fight

when the Axis is finally buried.

-

Autore secondario

-

William S. Friedman (Article Writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1943-01

-

pagine

-

70-83, 222-227

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google Digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)