-

Titolo

-

How America Has Developed the World's Best Automatic Weapons

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

How America Has Developed the World's Best Automatic Weapons. Yankee Inventive Genius, Plus the Lessons of the War, Give Us the Lead in the Arms that Are Making History

-

extracted text

-

AUTOMATIC weapons made history and changed the entire nature of warfare between 1914 and 1918. Auto-arms are dominating the present war even more completely, and have undergone superb technological development, ranging in size from the toylike .25-caliber dress pistols worn by staff officers in some European armies up to bulky quick-firing antitank and antiaircraft guns of 40 or 50 millimeters.

Machine guns and automatic cannon, rolling across Poland on tanks and motorized vehicles, blasted the Polish armies and cut their famed cavalry to ribbons in a matter of days. The underarmed Poles used their own weapons to advantage at a few points, and when it was over the Nazis—to show that they were broadminded—adopted an excellent antitank rifle of Polish design.

Parachute troops with light machine rifles and snub-nosed submachine guns captured bridges and canals, sprayed lead over air fields, and had a great deal to do with the swift collapse of the Netherlands. One type of Finnish submachine gun is credited with inflicting 70 percent of the estimated 250,000 Russian casualties in 1939-40. The lesson could go on indefinitely. Fire power wins battles, and automatic weapons provide heavy fire power for relatively small combat teams.

And it is good to know that the U.S. forces are being plentifully equipped with automatic arms which, on performance and history, probably can be called the world's best, flatly and without qualification. The list of American weapons is so long, in fact, that some might wonder why we have so many. The answer is that each has its peculiar function and mission in war.

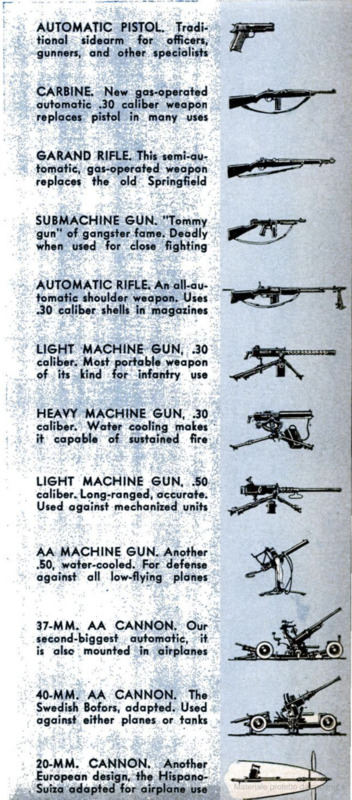

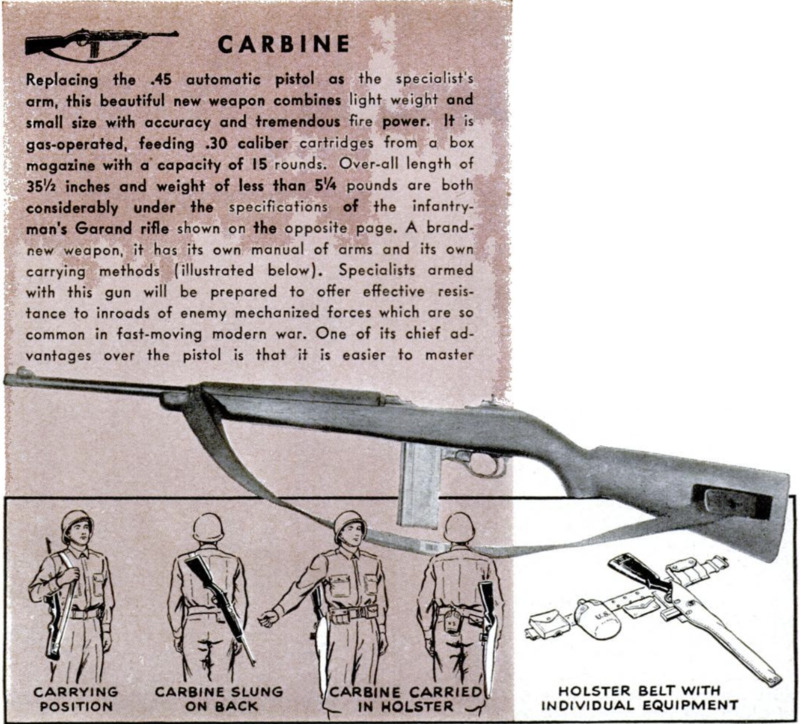

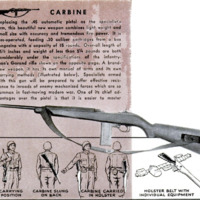

Starting from the bottom we have the famous Colt .45, the finest, surest, and hardest-hitting of all automatic pistols. This arm of officers, gunners, and specialists has a notable history, but it may be in its twilight, since the Army plans to replace it with the new .30 caliber M-1 carbine, a beautiful gas-operated rifle that weighs only 5.12 pounds and takes a 15-shot magazine.

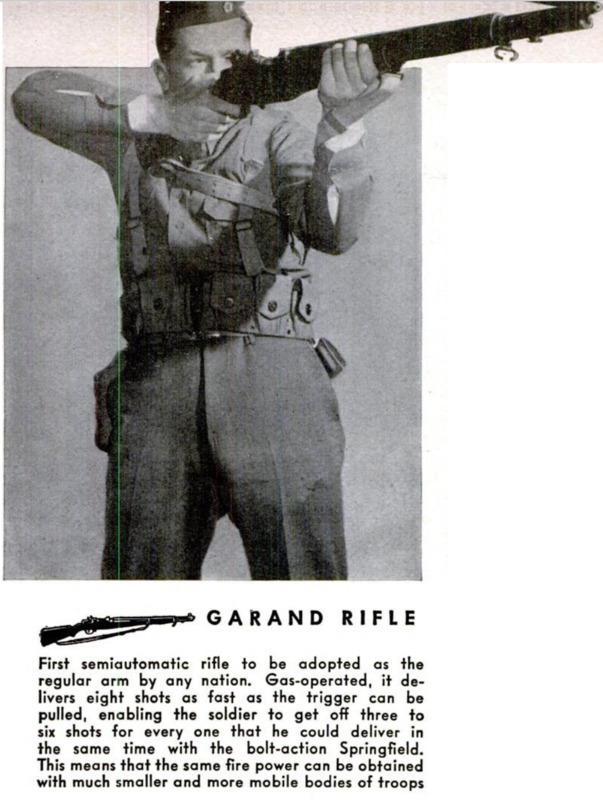

Next comes the most celebrated of new American arms, the Garand semiautomatic rifle, developed to replace the glamorous old Springfield as the standard shoulder arm of our soldiers, and the first weapon of this type to be adopted as the regular arm by any nation.

Between the admirers of the Garand and the Springfield there is no ill will. The Garand itself was developed at the Springfield Armory. Army riflemen explain it this way: In a peacetime competition they would take the Springfield with its unrivaled long-range accuracy and augmented fire power. The Springfield is a magazine

repeating rifle with a hand-operated bolt; the Garand is gas-operated and delivers eight shots as fast as the trigger can be pulled. The same soldier, in actual war, can get off three to six aimed shots with the Garand for every one with the Springfield.

There is a special bracket for submachine guns, of which the most notable is the celebrated Thompson (Tommy) gun. This is being turned out in large quantities not only for our own forces but for the British, who love it. (Ask the commando who owns one!) Two other American submachine guns have been developed, the Sedgely and the Reising. The Reising, made by Harrington & Richardson, has turned up with the U. S. Marines in the Pacific.

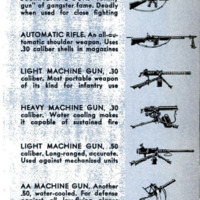

These submachine guns are highly portable weapons, spitting clips of pistol-type cartridges and capable of terrible execution at close range. Most popular calibers are the .45 and the 9-millimeter Luger type.

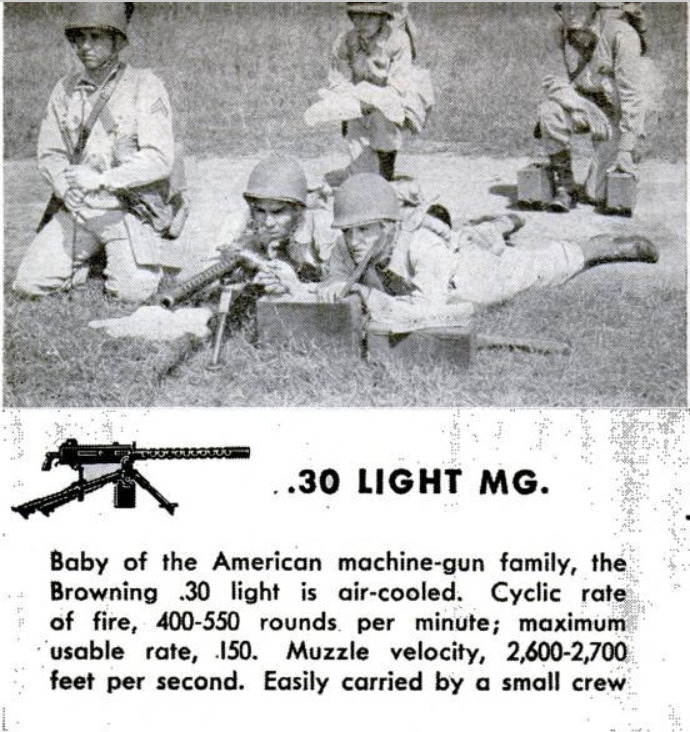

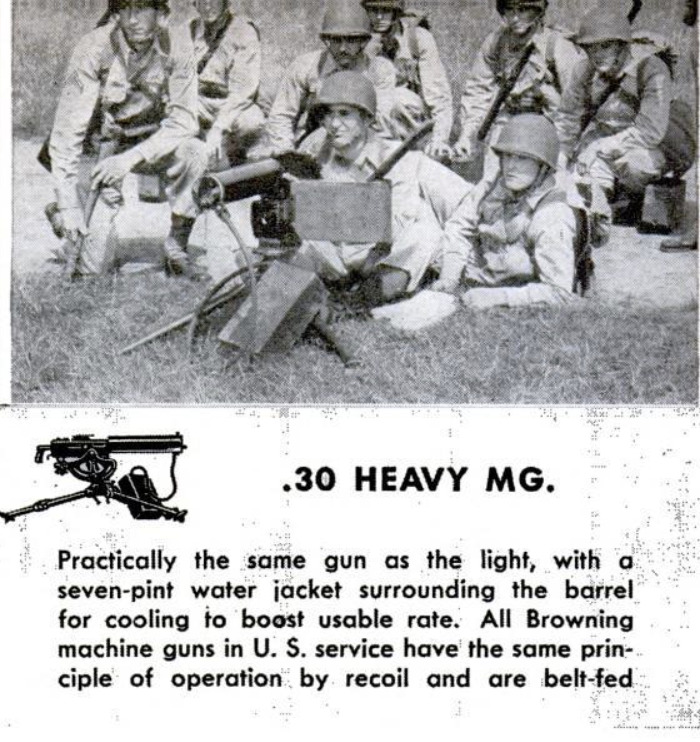

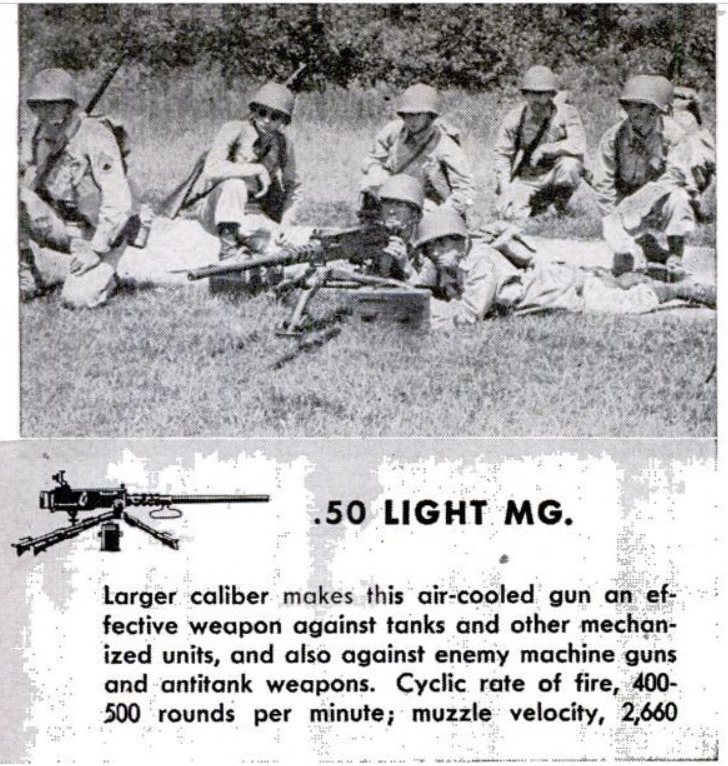

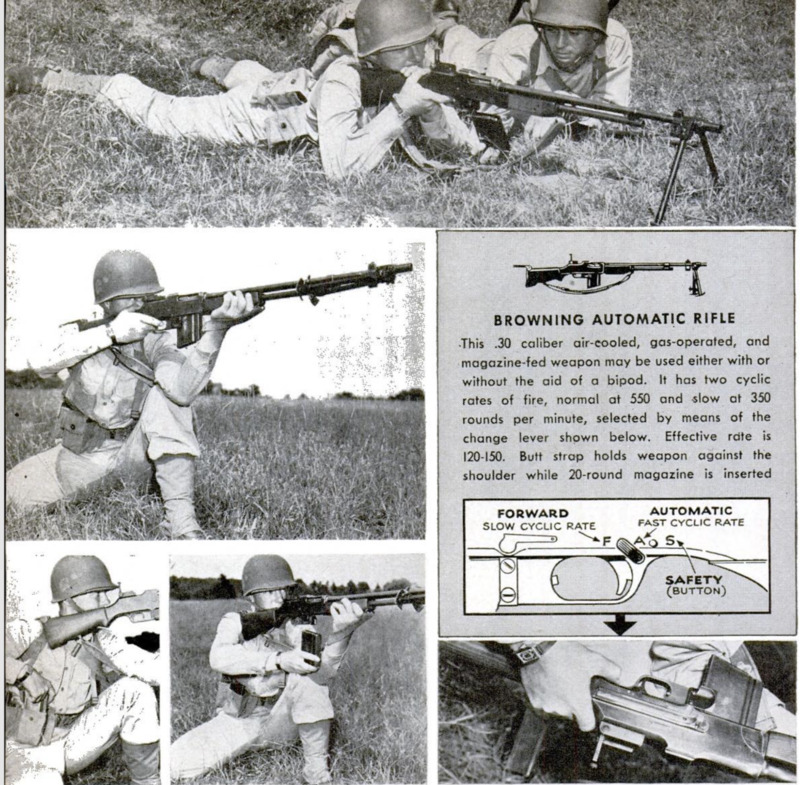

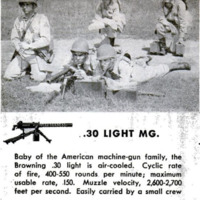

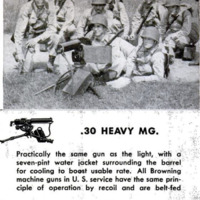

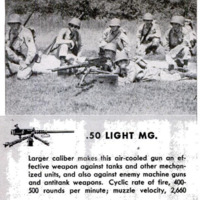

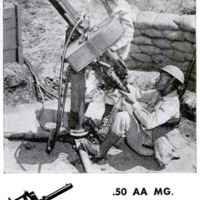

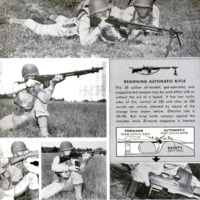

Above that comes the solid family of American machine guns: The Browning automatic rifle, or BAR; the .30 caliber light MG and the heavy, water-cooled one; the light and heavy .50 caliber guns. All are brain-children of the late John M. Browning, the world’s greatest inventor of automatic weapons, whose designs have been copied by most of the great powers and plenty of the small ones.

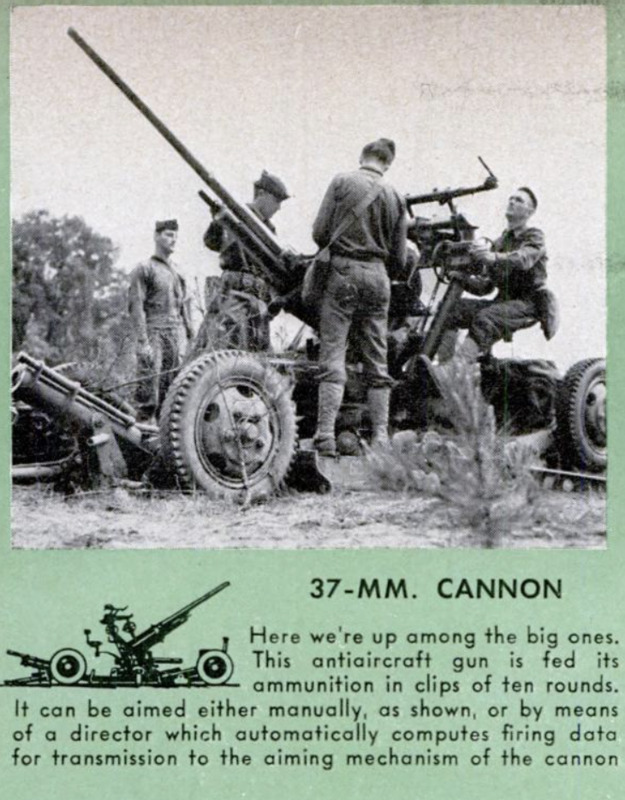

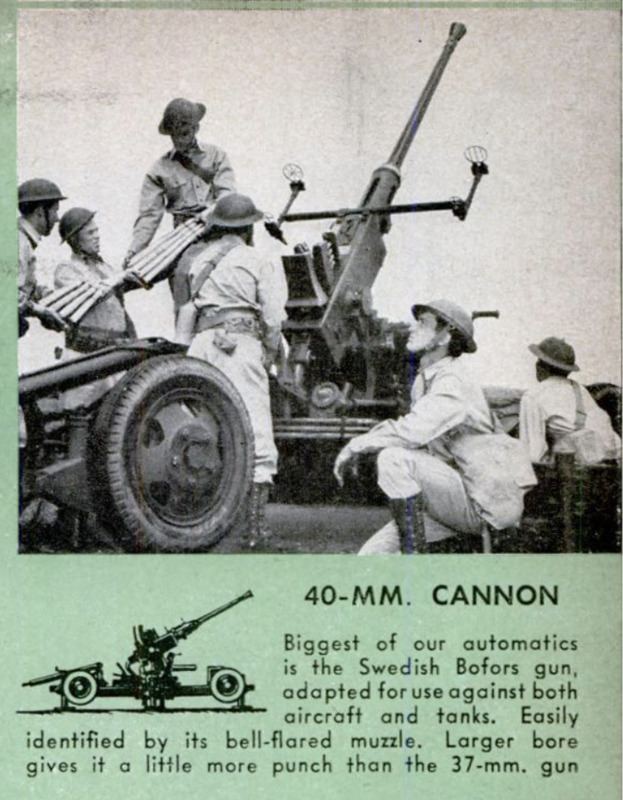

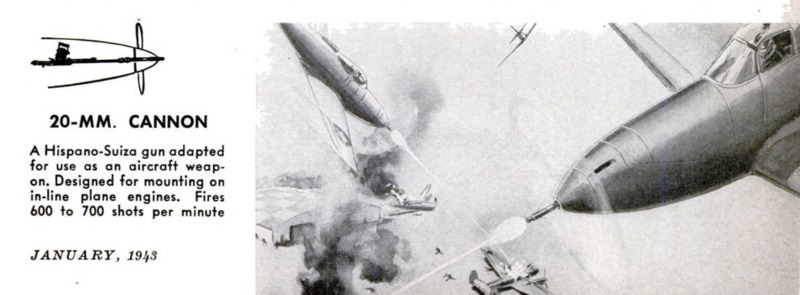

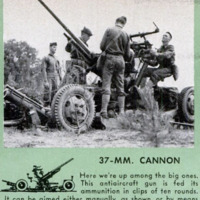

At the top are the 37-millimeter guns, for use in or against airplanes, and the 40-millimeter dual-purpose Bofors, which can be used against either planes or tanks. Then there is the 20-millimeter Hispano-Suiza, like the Bofors a European design, which we are now adapting as an airplane-carried cannon. The Navy uses a 20-mm. Oerlikon against dive bombers. Occasionally military writers speculate on larger automatic guns, and there would appear to be no technical reason why large artillery pieces could not be designed to load, aim, and fire by remote control, especially in antiaircraft emplacements. The limiting factors would be rather such considerations as size, weight, and mobility. Production figures on American manufacture are secret. But President Roosevelt disclosed last summer that in one month we had turned out more than 50,000 machine

guns. That did not include submachine guns. Those weapons are telling their own story now, in many parts of the world. The history of automatic weapons goes back into the early 16th century, and yet its entire significant development lies within the last two generations. Moreover, American gun experts, who were almost the last to tackle the problem, have made the most important advances.

As nearly as we can determine, the nameless genius who put together the first gun—some kind of wooden tube to blow out a missile with the force of burning gunpowder—must have started an hour later trying to do something about rapid fire.

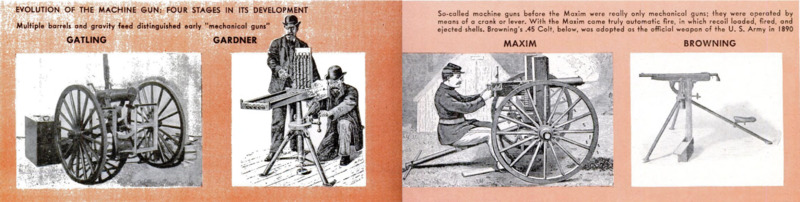

The first technique was several barrels on a single mount, discharged simultaneously, or in quick succession, by means of a powder train. The first certain use in battle was by Pedro Navarro, a Spaniard, against the French at Ravenna in 1512. The idea was amazingly persistent, and was still in use in our Civil War, with the “volley guns” of Billinghurst & Requa.

These were clumsy weapons with 24 barrels side by side between wide-set carriage wheels. The makers put on demonstrations in front of the New York Stock Exchange, but the Army showed little enthusiasm. The idea survives today with the familiar double-barrel shotgun and the four-barrel multiple anti-dive bomber guns British Navy men call “Chicago Pianos.”

The stumbling block for 300 years was the problem of igniting the powder charge. One design tried to meet this by loading along the barrel with successive charges of shot and powder. Touchholes were provided at suitable intervals, and the trick was to start near the muzzle and go down the barrel.

An automatic gun became a real possibility with the development of the metallic self-igniting cartridge, which could be discharged by the percussion of a hammer or firing pin. The first application resulted in mechanical rather than machine guns. As early as 1718, an Englishman named James Puckle took out a patent on a machine called a “Defence,” which in profile drawing looks amazingly like a modern machine gun. It had a single barrel and a set of revolving breech cylinders, turned by a crank, but it had to be fired by a slow match. Mr. Puckle couldn't resist including a provision to fire round bullets at Christian enemies and square ones at Turks.

The French developed a crank-operated gun, the mitrailleuse, between 1855 and 1869. This had 37 barrels in a circular housing like the barrel of a field gun, and was loaded with a breechblock clip having cartridge chambers lined up with the barrels. The gun had serious mechanical bugs and was misunderstood by the French, who used it as medium-range artillery rather than a close-range infantry weapon. Its failure in the Franco-Prussian War gave quick-firing weapons a black eye for years.

The first thoroughly successful mechanical gun was invented in 1862 by Dr. Richard J. Gatling, of Chicago. It had from four to ten barrels, revolving by crank power and firing from a breech mechanism with ammunition fed from a hopper. The Gatling gun was adopted and modified all over the world, and was in general use for

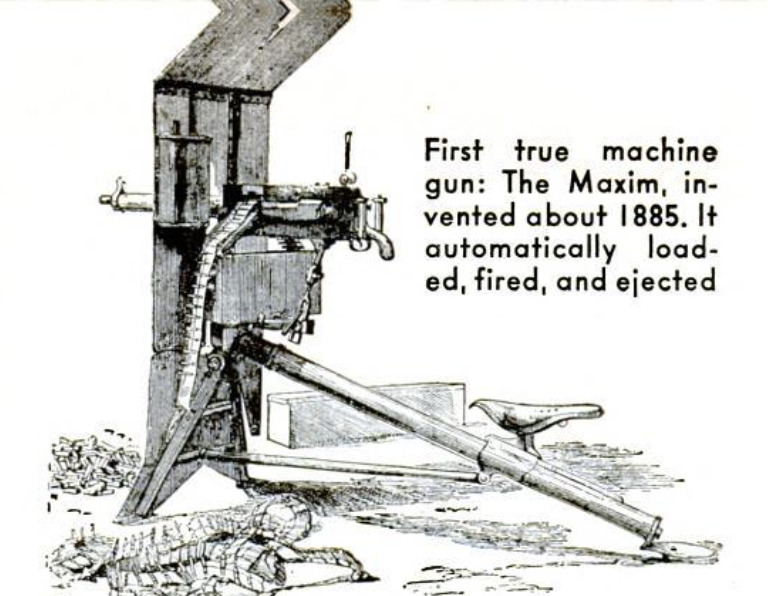

20 years after a genuine machine gun had been brought out. This first true machine gun, in which the shells were loaded, fired, and ejected in a continuous automatic cycle, was invented around 1885 by Hiram Maxim, a native of Maine, who later became a British subject. Maxim's gun employed the recoil of the explosion in the cartridge to move the bolt backward and eject the empty shell. Two heavy springs absorbed this motion, then

drove the bolt forward again, loading and firing another cartridge. Maxim also developed a belt feed. Since his gun had only one barrel, he designed a circular water jacket for it to prevent overheating. The next great basic invention was the Colt Browning gas-operated machine gun. Instead of using the recoil to actuate its mechanism, this gun had a tiny hole tapped in the underside of its barrel. A slight amount of the gases driving the bullet rushed into this opening, striking a piston and knocking down a lever which worked through a connecting rod and performed the ejecting, cocking, and loading. This was soon modified to employ a piston driven backward instead of down.

There are many variations of these two systems. Gun experts talk of “simple-blowback” or “delayed-blockback” recoil. And there are weapons in which the gas “expands” or “impinges” against the pis-

ton. Further differences exist in the manner in which the counter spring is connected with the gas-driven piston. But in general all automatic weapons are operated either by recoil or gas.

Even a superficial study brings proof of the dominant influence of American inventors. The celebrated German Luger automatic pistol, for example, is a modification of the toggle-joint action marketed in 1893 by a Connecticut man named Berchardt.

But American gun design reached its peak in the incredible career of John M. Browning. When he died in1926 on a visit to Belgium, his body lay in the great National Arms Factory at Liege. During the World War he had been decorated with the Belgian Order of Leopold at the completion of the 1,000,000th Browning pistol there.

Browning designed weapons for all the great American companies—the full line of Colt automatic pistols, including the .45; most of the Winchesters for 30 years; autoloading shotguns and rifles for Remington and Stevens.

He was born in Ogden, Utah, of Mormon parents. His father, Jonathan Browning, had run a gunshop in Council Bluffs, Iowa, before moving west. In his early teens, Browning made a rifle: by 1880 he had designed a single-shot weapon that opened the eyes of Winchester’'s experts, and ten years later his Colt Browning machine gun was adopted as the official weapon of the U. S. Army. Browning's fame didn’t reach the public, however, until the first World War, when it was suddenly announced that our Army was adopting an entire new family of machine guns designed by an “unknown” named Browning. They are still our standard—the handy shoulder-operated Browning Automatic Rifle; the light and heavy 30's for use against personnel; the enlarged .50-caliber MG with its extra punch against airplanes or light vehicles. The BAR is gas-operated, the others by recoil.

America has designers today carrying on the tradition. Will they produce new weapons to blast our enemies? Well, new weapons are necessarily secret weapons in war time, and our Ordnance chiefs say only that surprises are in store.

But it is not out of line to discuss two “surprise” weapons now no longer secret—one of them a new gun in this war, the other a World War invention which missed fame by the accident of time.

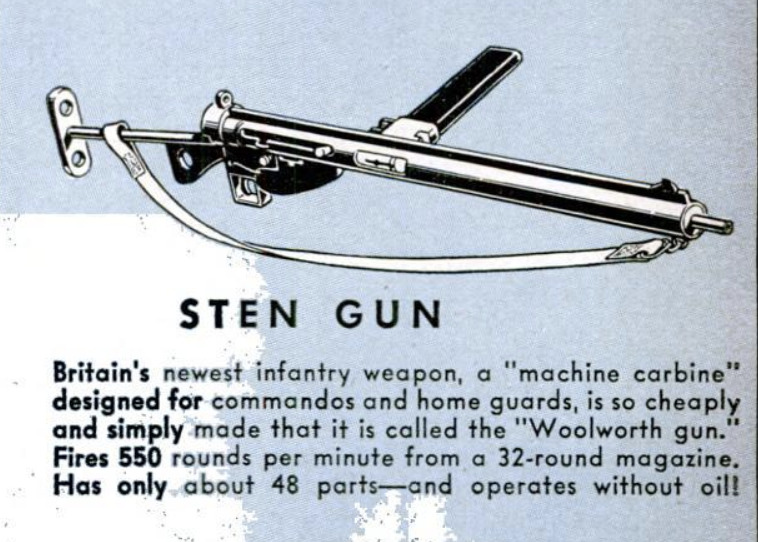

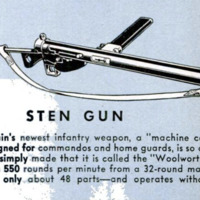

The first is the British “Sten” gun, a slightly overgrown machine pistol which looks almost comically like a youngster's popgun but throws a murderous stream of slugs at short range. It is being massproduced for less than eight dollars a gun.

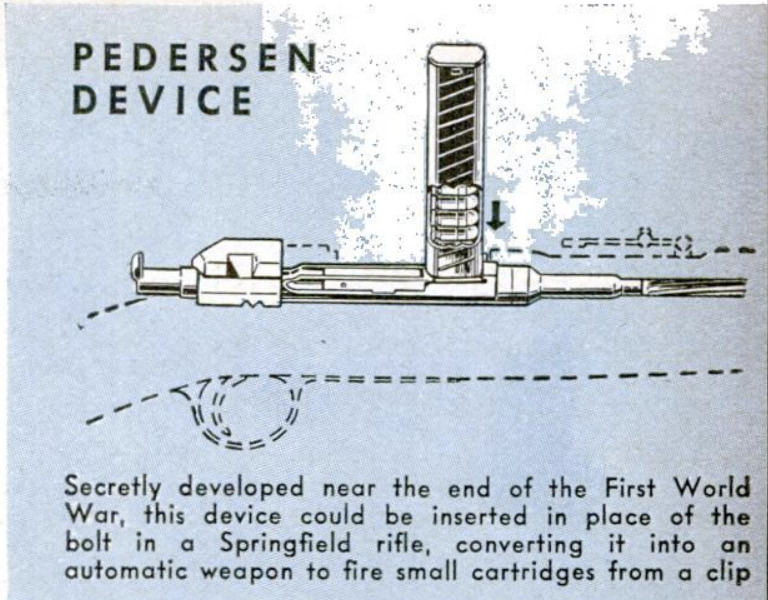

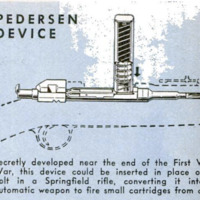

The second gun was the mysterious “Pedersen device.” It was officially known as the “U. S. Pistol, caliber .30, Model 1918.” That was done for secrecy, so that even the workmen who made the parts wouldn't realize what they were doing.

Actually the Pedersen device was a special bolt-and-breech assembly designed to replace the standard bolt of the 1903 Springfield and convert it into a submachine gun, spitting out 80-grain bullets from a detachable 40-shot box magazine.

More than 80,000 of these bolts were ready when the Armistice came in 1918; unquestionably they would have been one of the meanest surprises of the war. They were scrapped when development of the submachine gun and automatic rifle outmoded them. But it may be that something as ingenious and lethal is in the making.

-

Autore secondario

-

John H. Walker (writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1943-01

-

pagine

-

124-131

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google Digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)