-

Titolo

-

Combat Planes that support U.S. Navy

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: Our Navy strikes from the Sky

-

Subtitle: Here are the combat planes that support our sea power

-

extracted text

-

AS THE war wears into its third year, no

doubt remains that the air arm holds

the margin between victory and defeat. At

sea, as the reports of naval action roll in, it

becomes increasingly apparent that the

great naval vessels that once were the back-

bone of naval strategy have been trans-

formed by the shifting pattern of events into

bases and auxiliaries for aircraft.

The reason is simple. A carrier with its

nest of planes can throw destruction farther

and faster than the best ship of the line. For

pure deadliness, for accuracy and economy

of fire, the dive bomber outstrips the big

naval gun by a fearful margin. The torpedo-

carrying airplane, backed by speed and

maneuverability which no surface or sub-

surface vessel can claim, scores fewer misses

per run-in than even the swift mosquito

boats. In modern naval action, the airplane

is in turn scouting force, ordnance, defense,

and light transport all rolled into one.

The importance to which the air phase of

naval warfare has mounted in recent months

is best exemplified by a side-light story that

has leaked out of the Coral Sea engagement.

A complete battle unit, sent out to overhaul

and cancel a major Jap carrier, had com-

pleted its task. A straggling scout bomber

arrived at the flat-top only to find her in

flames and listing. No use wasting the

valuable missile on her. The pilot scouted

for an alternative target and spotted an

enemy light cruiser. When the bomb hit,

the ship almost tore in half. The pilot then

proceeded back to his carrier, bombed up

and refueled and went out again on another

trip. It was not until much later that the

sinking of the cruiser came to light. When

the check-up was made as to how each bomb

was disposed of, the pilot admitted a little

apologetically that he had expended the

bomb on a mere light cruiser. Since it was

a non-airstrength vessel, he deemed it of so

little importance that reporting it classed

with landing an undersized fish that should

have been thrown back. Anything less than

a carrier is rated fairly small game.

Running an air navy is a complicated

business. Unlike land operations, new and

altering conditions have dictated unexpected

changes in design requirements for its air-

craft and general approach of operations.

Naval aircraft are divided into three classes.

Before the war, there were only two. First

there are shipboard airplanes, the carrier-

based fighters, scout-bombers and torpedo-

planes; cruisers carry catapult observation

craft. In the next class are harbor-based

long-range seaplanes; patrol craft and bomb-

ers, and far-ranging torpedo carriers by

turn. The newest category is that of land-

based scout-bombers. This is an innovation

gotten from the critiques of the battle of the

Coral Sea and from direct experience in

anti-submarine patrol.

Early carriers were converted freighters,

colliers, and similar makeshifts. Japan's

first flat-tops were heavy cruisers with

temporary landing decks, created in evasion

of the terms of the Washington Conference

which limited naval construction. The plan

was, when the time for war came, to alter

the supérstructure, mount heavy guns, and

send the ship to sea as a cruiser. It is an

odd reflection on the turn of the war to dis-

cover that many of the current Jap carriers

were originally laid down as cruisers and

other craft and hastily converted to swell

the carrier tonnage.

Our carriers are stocked with three basic

classes of aircraft: fighters, scout-bombers,

and torpedo planes. Their functions are

simple. The fighter protects

the carrier from enemy attack

or accompanies the scout-

bomber or torpedo plane to

its point of attack, fending

off the enemy interception.

The scout-bomber does some

of the scouting, but its chief

job is that taken over from

the big guns; diving down

and accurately planting ex-

plosives directly onto enemy

objectives — ships, land in-

stallations, etc. The torpedo

plane bears the deadliest marine missile

of all, the “tin fish” which it can haul

prodigious distances at high speed and carry

closer to the objective than any destroyer

or PT boat. As a destructive weapon, it

can take over one of the destroyer’s nastiest

jobs, completing it for a great deal less in-

vestment in equipment and risking a smaller

crew. The torpedo unit-casualty score be-

tween the four usual torpedo media—the

submarine, destroyer, mosquito boat, and

plane—gives the plane a fairly wide margin

when operating against armed surface

craft. Several things are in the plane's

favor. First there are fewer men (three)

involved in a torpedo-plane attempt. The

plane is the smallest target, moving at a far

greater speed. Both the destroyer and the

torpedo boat have one dimension of fire

fixed: they must be on the surface. The

submarine and the airplane alone may op-

erate at a multitude of levels and angles, in

a three-dimensional battleground. The sub

is definitely limited as to the depth at which

it can move in its medium and has a speed

inferior to most of its targets.

Most cruisers and carriers also carry a

few light, low-powered, far-ranging scout

observation planes such ag the Curtiss Sea-

gull and the Vought-Sikorsky Kingfisher,

either on wheels for straight deckboard op-

eration or on a single float, to be catapulted

off for fire correction for a cruiser’s guns.

The type's low power and light armament

make them so vulnerable that many naval

authorities discount them, and often their

duties are transferred to ships better cap-

able of combat.

Carrier planes are, at present, in the

process of transition. Changes in naval

types have necessarily been slower than in

those operated from land bases. To begin

with, types are changed in response to

known needs, actually shown in battle. Be-

cause Japan was the first enemy to come out

with any appreciable carrier strength, major

replacements had to be made only after the

facts were known. For the most part, our

types had adequate performance to hold

the enemy. The changes are made so that

we can not only keep ahead of him, but

boost performance by a large enough margin

so that we can positively and finally wrest

control of the air over the sea lanes. The

remainder will then be a fairly simple mili-

tary operation.

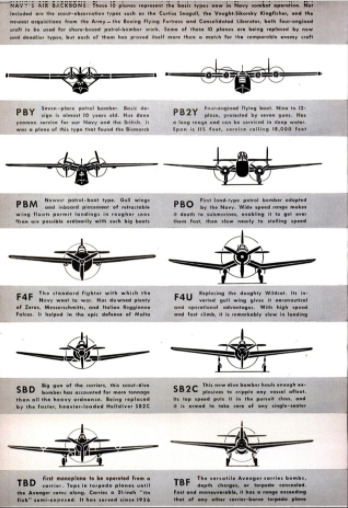

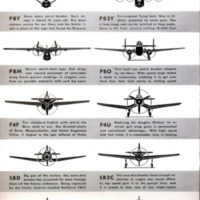

Our Navy went into the war with three

basic deckboard types. One was the Grum-

man F4F, affectionately known as the Wild-

cat. It was a nasty, stubby little airplane

with a 38-foot wing span. It weighed a bit

over 5,700 pounds, its top speed was above

340 miles per hour. It was armed with four

.50 caliber machine guns and hauled enough

gas to take it 1,100 miles.

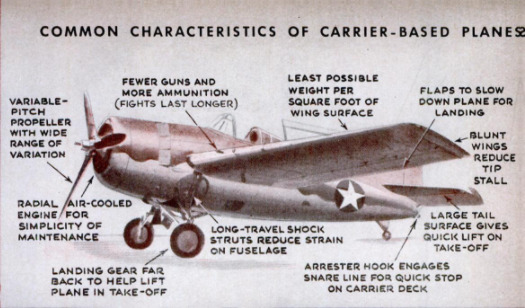

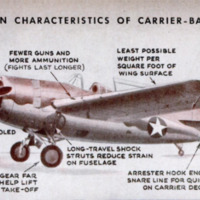

It is a mistake to compare such per-

formance with that of the Hurricane, Spit-

tire, Warhawk, and other fast land-based

fighters. Shipboard-aircraft design is limited

by certain factors which do not affect the

land-based fighter. The entire landing area

for the shipboard fighter is the carrier deck

—300 yards long at the most. The fighter

must be off in a fraction of that. The fight-

er’s dimensions are limited by the elevator

facilities on existing carriers. Its range

must be almost as great as that of the dive

bombers and torpedo planes it is destined

to escort.

The shipboard fighter must have superior

maneuverability. In land fighting, it is pos-

sible for the attacking plane to make a

single pass at the enemy, but the carrier

ship must stay and fight. In the first place,

there are only a limited number of fighters

available. If the

fighter lets the enemy get by, he is likely to

have no carrier left to land on.

The gun-ammunition ratio in a naval

fighter is different from that of a land plane.

The average Army job calls for a major

weight investment in gun power for a with-

ering blast at the enemy, enough to make

the ship disintegrate. However, the ammuni-

tion allows only a short duration of fire. This

is based on the patrol system upon which

land fighting is predicated—the availability

of large numbers of airplanes so that if an

enemy force resists or evades one blast,

other ships can be sent to intercept it. The

carrier goes to sea with a definite number

of planes and replacements; additions or

reinforcements are simply unavailable. In

the carrier fighter, fewer guns are mounted,

most of the fighting weight being invested

in ammunition. In a concentrated naval ac-

tion, a Wildcat is likely to be attacked sev-

eral times. Therefore, being able to sustain

fire is vital. This puts great stress on the

quality of marksmanship.

There is a widespread belief that deck-

board fighters land much more slowly than

land-based pursuits. Actually, this is not

true. Having more room to land in, the

land-based Army fighter pilot can bring his

ship in on power, flying it parallel with the

field and settling slowly, losing the last of

his flying speed close to the ground. The

Navy fighter, on the other hand, has a frac-

tion of a moving quarter-acre deck to sit

down on. Each landing must be “full stall,”

that is, the ship must be brought in slowly

and, by the time the wheels touch the deck,

the wings must be devoid of lift. This re-

quires great lateral control at slow speeds.

This need, combined with the demand for as

much wing area for the span as is possible,

produces the stubby, square-tipped wing that

has made the Wildcat one of the most popu-

lar types ever

stocked for deckboard use. Even the British

admit that the F4F-—or Martlet, as they

call it in the Fleet Air Arm—is among

the hottest craft that ever dropped an

arrester hook on His Majesty's carriers.

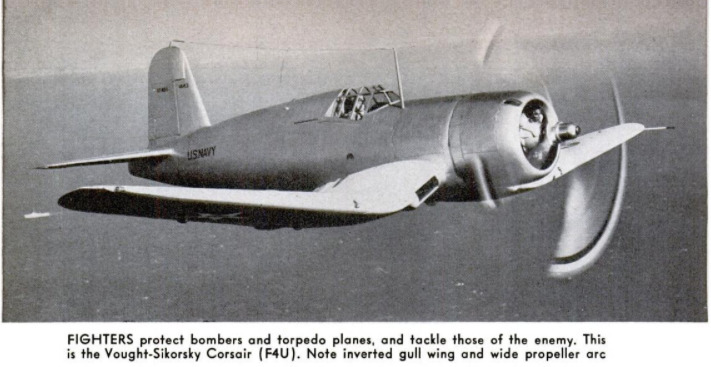

The Wildcat, excellent as it is, must be

replaced. Carrier action in amphibious war-

fare often dictates that the deck-board fight-

er meet land-based fighters or intercept

high-altitude bombers. The next ship in line

seems to be the Vought-Sikorsky F4U-1, the

Corsair. A little bigger than the Wildcat, it

weighs almost twice as much, carries more

guns, and sustains a longer rate of fire. Its

2,000-hp. engine provides it a phenomenal

climb and a service ceiling closely approxi-

mating that of the best-known land-based

fighter craft. Most figures on the Corsair

are under restriction, but is safe to say that

total replacement of the older type will be

possible soon. There are several other nasty

surprises scheduled for the enemy. One of

them has acquired the affectionate nick-

name of “the big beast,” and the early re-

ports on its performance indicate that it is

turning out to be a terror.

Scout Bombers are the big guns of the

modern air fleet. Fast, quick-in-quick-out

ships, their job is to power-dive in at as

steep an angle as they dare. The diving

sight is the same instrument that is used to

direct the ship's forward fixed guns. The

technique of dive bombing has altered con-

siderably since the Navy first demonstrated

it over ten years ago. Originally, the pilot

merely glued his sight on the target and

dived the ship dead on,

pulling out at as close

an altitude as he consid-

ered safe. The first dive

bombers were wire-and-

strut biplanes, and their

parasite resistance kept

the airplane from gath-

ering an uncontrollable

amount of speed.

Since that time, anti-

aircraft tactics have been

improved, so that a pilot

attempting the old-fash-

ioned straight bombing

dive would be a dead

duck and even the high

speed of his ship would

be little protection. The

modern dive bomber is

an exceptionally clean

airplane, and uncon-

trolled diving would per-

mit the accumulation of

more speed than is neces-

sary or useful. To control

this excess speed in a

dive, air brakes are em-

ployed. The popular U. S. design is a double

perforated flap at the trailing edge of the

wing which sweeps both up and down, in-

creasing the resistance and decelerating the

airplane. The old-fashioned direct dive has

been changed to circuitous approach pat-

terns which are highly varied and often

completely unpredictable. As the bombs

that the dive bomber carries increase in size,

it becomes necessary to release them at a

higher altitude to prevent their explosion

from wrecking the plane as well as the

target.

The currently used craft is the Douglas

“Dauntless,” which hauls a single 500-pound

bomb 1,000 miles at a speed exceeding 250

miles per hour. The Dauntless has an un-

equaled record in the Pacific. It was in this

type that the immortal Lieutenant Powers

“laid one on the deck” of a Jap battlewagon,

carrying it to less than 500 feet and going

down with his victim.

Oddly enough, the Dauntless is being re-

placed, not because it could not do its job,

but because it was so successful that it

proved for all time that dive bombers could

be trusted with practically every job ever

given to a full naval gun. The only thing it

lacked was the heavy-weight missile. The

Curtiss Helldiver, the SB2C, built to haul

four times the Dauntless’s bomb weight for

1,200 miles at a greater speed, is now swing-

ing into full production. This type is capable

of sinking almost any vessel afloat all by

itself. Armed more heavily than its pred-

ecessor, it can, if necessary, fly to an ob-

jective with a minimum

of fighter support. In the

Dauntless, the bombs

stowed externally, caus-

ing considerable parasite

resistance in the air. The

speed difference, checked

agains actual tests, indi-

cated a 15-m.p.h. differ-

ence without the bombs.

As a check, 500 pounds

of dead weight were

stowed inside for the

comparative run. In the

Helldiver, the bombs are

stowed internally.

Unless you count the

helpless cargo craft sunk

by submarines, the tor-

pedo plane is tops in the

sinking of war tonnage.

So far, the only sure cure

for the torpedo plane is

the fighter. Until recent-

ly our fleet has been

equipped with the TBD,

the old Douglas Devas-

tator, the first monoplane ever to be op-

erated from a carrier. Developed from the

Douglas XT3D-1, it went into service in

1936 and has served, unmodified and un-

changed, until its duties were taken over by

the newer Grumman TBF or Avenger.

Of all carrier jobs, this is admittedly the

toughest kind of flying. Even on deck, be-

fore take-off, its 50-foot wing is folded back,

and the pilot has to taxi into line by forward

signals from the yellow-shirted trafic man.

He must unfold his wings as he goes, mini-

mizing the time loss between ship take-offs.

Having to haul the greatest load the great-

est distance, the TB usually is the lightest

armed of the three general classes. The

fighter has its maneuverability and its arma-

ment to Keep it safe, the dive bomber has

enough guns to keep it out of trouble and

can, if necessary, outdive the attacker. The

torpedo bomber, however, is a sitting duck

in the average set of approaches and re-

quires, for the most part, fighter escort.

The Devastator served a longer useful

career than any single fighting design in the

Air navy’s history. While she will probably

still be seen around for many months to

come, the Coral Sea action indicated the

need for a ship that would not require quite

such close attendance on the part of the

fighters. The Navy needed a more versatile

major air vehicle for the carriers. The re-

sult was the TBF, the Grumman Avenger.

The Avenger bears a strong family resem-

blance to the Wildcat, and a lot of the claw-

ing F4F’s characteristics remain. The

Avenger carries the 21-inch Bliss-Leavitt

‘torpedo internally rather than semiexposed

as in the Devastator.

‘The Avenger’s total armament is close to

that of a fighter, although not concentrated

in one place for maximum effectiveness. It

is not designed to look for combat. However,

with guns forward, in the turret, and

through the belly, it is a nasty customer to

tackle. Unlike the TBD, the Grumman can

be used to lay depth charges or carry a

load of bombs well above 20,000 feet.

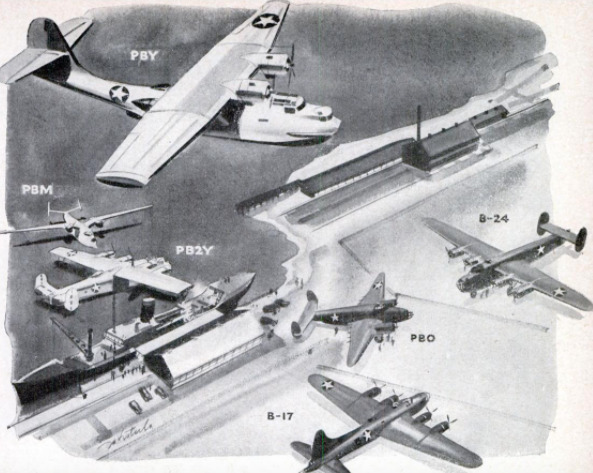

‘This is the current stock for the carriers.

As for shore-based planes, the Navy is op-

erating several types of long-range land

planes. Prominent among these is the PBAY,

the Consolidated B-24 four-engined bomber

known as the Liberator. The Lockheed

Ventura, designed to take up where the

famed Hudson left off, was borrowed from

the English to become the PBO. The B-17,

the Boeing Flying Fortress, will appear

shortly in Navy stripes. In actual warfare,

many basic weaknesses were discovered in

the operation of large flying boats. The main

shortcoming was the fact that no flying boat

could be equipped with a gun emplacement

in the bottom. More than a third of the

hull surface is totally blind area.

The remainder of the PB series is invested

in the traditional flying boats, currently the

PBY or twin-engined Catalina boat; the

PB2Y, its big brother, the four-engined

Coronado; and the PBM, the Martin Mariner.

This type has been designed primarily for

long-range overseas scouting, accommodat-

ing crews of between seven and 15 men.

They are capable of remaining in the air

over long periods regardless of the vagaries

of the weather. When used as bombers, they

must be capable of getting out of the water

with large loads of bombs, depth charges, or

torpedoes and must carry enough defensive

armament to compensate for their relative

slowness.

‘The flying boat has many operational ad-

vantages. Any sheltered strip of water is a

base for a seaplane. In ordinary weather, a

seaplane tender, a small, inexpensive ship,

can service it and keep it going even at sea.

Furthermore, the development of remote-

control firing positions now under investiga-

tion may reduce the blind-spot objection. |

Now that the pattern of sea-air warfare

has been established, modifications in naval-

plane design must be made accordingly. Al-

though it has been a close fight, one major:

portion of the victory is already ours. This

is the battle of design philosophy.

Japan planned for a quick victory at sea.

She planned to pay for it by sacrificing pilot

and air-crew safety for a small percentage

of climbing and turning ability. Japan's

engine development lagged behind ours. The

largest power plant she has exhibited this

far is about 1250 horsepower. To achieve

performance with these smaller engines, she,

had to pare down size and weight. The re-

sult was the Misubishi Zero and her series

of dive and torpedo bombers, Light and un-

armored, these ships disintegrated under

fire. The newer series of Jap fighters indi-

cate a trend toward armor and self-sealing;

tanks. Not that Japan has acquired any,

more respect for human life, but that the

pllot losses have been greater than she could

afford for the amount of air control she thus

far has gained. This means that Japan must

scrap a lot of her research, alter production,

and plug the gap with makeshifts, Chang-

ing her mind is going to cost her the war,

-

Autore secondario

-

William S. Friedman (Article Writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1943-02

-

pagine

-

68-77,233,235

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google Digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)