-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Blueprint for invasion

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: Blueprint for invasion

-

Subtitle: Careful preparation and long, elaborate training lie behind a landing on a fortified enemy coast

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

SOMEWHERE off a hostile coast, in the

damp cold an hour or two before day-

break, infantrymen clad in heavy water-

proof suits take their places in shallow-draft

assault boats. They may embark from an

island or other land base within striking

distance of their objective, or from trans-

ports screened by a naval force. Bigger as-

sault craft, resembling vehicular ferryboats,

are loaded with tanks and field guns. Every-

thing has been rehearsed: in a short time

the assembled armada is churning toward a

designated point on the coast. The curtain

has risen on the drama of invasion, but the

stage is still dark.

If luck is with the attackers, they may

catch the enemy napping and the first units

may land without opposition. But at some

point in the operation hell breaks loose. The

sky explodes in orange flares amid the rattle

of machine guns and the bursting of bombs

and shells. The assault boats hit the beach,

their bows drop like drawbridges and the

men and tanks swarm ashore. The leading

units snip the barbed-wire entanglements

with cutting tools and clear the way for the

main attack. Assault engineers blast barri-

cades and open roads for heavy equipment.

Mortars and fieldpieces set up on the beach

cover the advance.

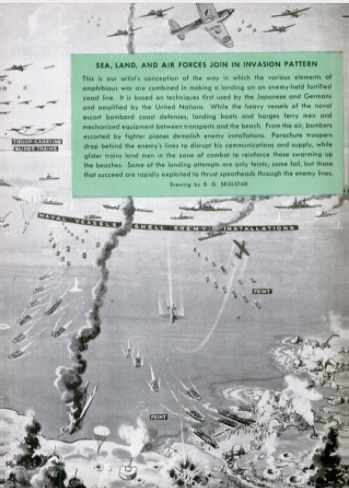

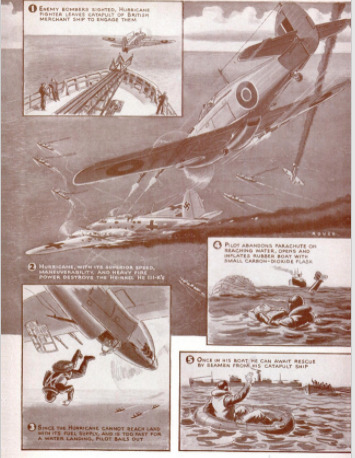

This is aero-amphibious war, and the ac-

tion is not confined to sea and land. Air-

planes fight overhead. Parachute troops

drop from transport planes and infantry-

filled gliders are towed into the zone of ac-

tion. As the operation develops every type

of soldier takes part. Smoke screens are laid

by chemical-warfare units to conceal the

successive waves of assault boats which,

hour after hour, ferry infantry, armored

forces, signal and medical units, and detach-

ments of all the arms and services to the

disputed beach. The issue is decided in a few

hours: either the attackers are driven back

into the sea with disastrous losses, or they

have thrust the spearhead of invasion into

the enemy's coastal defense line.

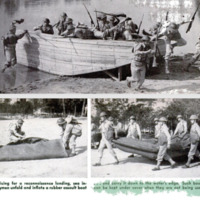

Since the fall of France and the evacua-

tion at Dunkirk, the military experts of the

press and radio have been warning us that

landing on a hostile coast is the most costly,

difficult, and hazardous of military under-

takings. No doubt there is much truth in |

these cautions—but they did not worry the

Germans too much when they wanted Crete,

nor the Japs in their leapfrog advance from

Formosa to New Guinea. Nor have they

ever worried the United States Marine

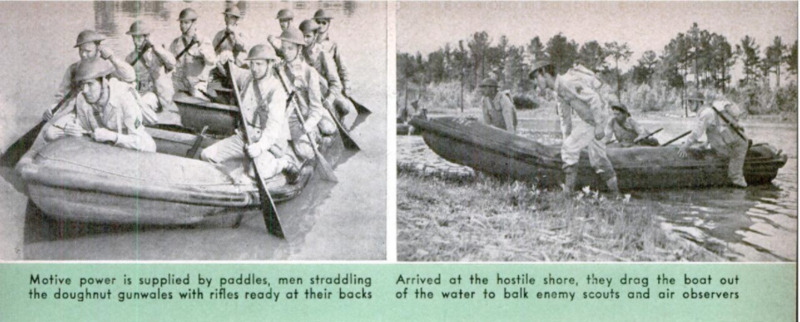

Corps. With their rubber assault boats,

amphibious tractors, transport planes, and |

gliders, the Marines have pioneered in many

phases of invasion technique The only trou-

ble with them is that they are a compara-

tively small outfit, and large-scale invasion

calls for quantity as well as quality. Our

landings in Africa have shown how well

their technique can be applied on a large

scale.

The Japs went into the invasion business

in a small way in China and graduated into

the big time later. They developed a definite

technique which is worth studying. In all

cases they first reconnoitered landing sites

carefully from the air. Besides, they had

been there before, fishing and so on: thus |

they knew the country and had good con-

nections ashore. When they came to cap- |

italize on their preparations it was usually

with a task force comprising a battleship

or heavy cruiser, an airplane carrier if re-

quired, destroyers, and enough transports to

carry about two divisions (40,000 men) with

normal equipment, including 75-millimeter

field guns and 105-millimeter howitzers, and

light tanks. Almost always they arrived

just before dawn, on a day when high tide

came-soon after dawn. The battleship stood

out between three and four miles, the de-

stroyers lined up about half a mile out, the

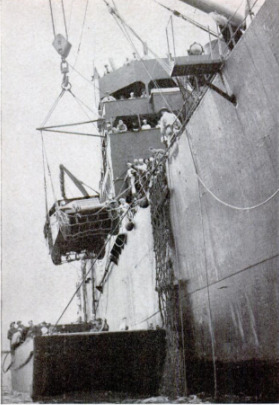

transports were in between. The troops

climbed down the sides of the transports

into landing boats, or, in some cases—this

was an original idea which they apparently

developed from the design of whaling ships

—side hatches opened and the boats, al-

ready loaded, slipped into the water.

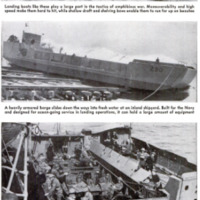

The landing barges comprised several

types, the largest holding about 120 men,

while smaller ones carried 50 or 60 men

apiece. Speeds were about 10 knots. The

boats were generally armored in the bow

and stern. Those carrying tanks or artillery

were equipped with a bow which could be

lowered, somewhat like a bascule bridge,

forming a ramp down which the equip-

ment could be wheeled off.

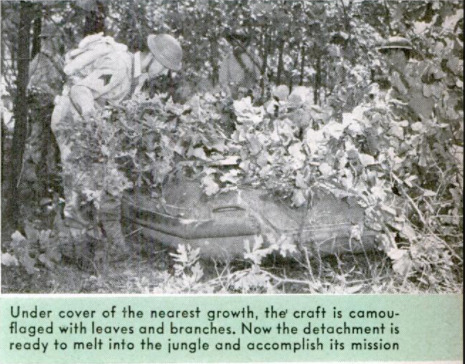

The boats also had other advantageous fea-

tures, such as double keels for stability

when they were beached. They were, of

course, shallow-draft craft which could get

high up on the sand before grounding. One

type was a hydroplane, airplane-propeller-

driven, for use in creeks, weed-bound water,

and the like.

The Japs used their men and equipment

skillfully, taking full advantage of surprise

and secrecy. They always saw to it that

they had air superiority. By the time they

were discovered they usually had a sizable

force on shore and under cover. Then their

aircraft were swarming overhead and the

guns of the fleet protected the balance of

the landing.

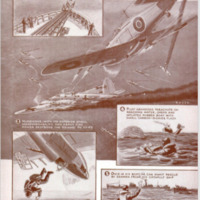

The Germans at Crete relied more on air

power than on such a balanced combination.

Actually they likewise started with a sea-

borne force, but their intelligence service

proved deficient in this instance: the strength

of the British was several times greater

than had been estimated. The Germans

then shot the works in the air; they were

able to do this because enough land-based

aviation was available and preparations had

been made for just such a contingency.

They came in gliders carrying 12 to 30 sol-

diers apiece, towed by lumbering old trans-

ports which were perfectly suited for this

new job. As many as 10 or 11 gliders were

strung out behind each towing plane. They

also used parachute troops, and, when they

had captured an airport, ferried their infan

try across the water in transport planes. By

these methods, in a few days they landed

15,000 troops on the island, equipped with

rifles, light and heavy machine guns, field-

pieces, medical supplies, and about every-

thing else they needed.

This operation has been carefully analyzed

by our Army. Lieut. Gen. Henry H. Arnold,

the chief of our Air Forces, refers to it as

the “awful lesson of Crete”—the lesson be-

ing that neglect of air power as a para-

‘mount factor in invasion is a fatal error, and

that we must not only take into account air

power as it exists today, but beat the enemy

to the punch in new developments.

The general pattern which emerges is

fairly clear. To get a foothold on a hostile

coast, and to hold and enlarge that foothold

with reasonable assurance of victory, one

must have air superiority, naval superiority,

and ground superiority. The three factors

are not concurrent; more precisely, the re-

quirements are initial air and naval sus

periority, with a view to converting poten-

tial land superiority into actual land su-

periority in the course of the operation.

One may win with only initial air superior-

ity, as the Germans did at Crete, but to do a

workman-like job, with the utmost economy

of men and matériel, one should possess

preponderance in all three elements. And of

course these elements are not to be regarded

as disparate. When the opposed forces areanywhere near equal, the deciding factor is

the co-ordination between air, sea, and land

forces, These must be under unified com-

mand. Landing operations are a peculiarly

clear illustration of the principle that the

strategic whole is all that counts—the parts

matter only in so far as they contribute to

the whole.

In our own Army progress in this direc-

tion 1s reflected in many ways. One which

stands out is the organizational setup of the

various arms. As long ago as November

1941, Lieut. Gen, Hugh A. Drum argued that

the “present watertight compartments” ex-

isting between air support, armored forces,

and other arms must be broken down. They

are being broken down. The basic classifica-

tions still exist, but there are numerous new

combinations which at first sight are rather

puzzling. We find, for instance, the En-

gineer Amphibian Command—ot the Army

—recruiting sailors, commercial fishermen,

and marine specialists of various kinds, the

purpose being to get fighting men ashore

Where they can attack the enemy, and to

maintain the craft which will do the job.

This command alone is recruiting men from

40 different flelds—automobile service men,

crane operators, lifeguards, plumbers, sheet-

metal workers, and surveyors being a few of

them. Then we have a Special Service Force

equipped to engage in parachute, marine

landing, mountain, and desert operations.

Also to be mentioned is the Airborne Com-

mand which links the Air Forces and the

Ground Forces, but belongs organizationally

to the latter, while the Troop Carrier Com-

‘mand, likewise a bridge between Air Forces

and Ground Forces, belongs organizational-

ly to the former.

After a little study one gets the logic of it.

These hybrid military units, and their inter-

connections with the Navy, reflect the in-

creasing complexity of modern warfare, the

need for teamwork and continuous co-ordi-

nation among the arms and services. The

more specialized the soldier's task becomes,

the more necessary it is to integrate the ef-

forts of the specialists so that they will

serve that strategy of the whole which, on

pain of disaster, must never be neglected.

And the orientation of the whole complex

setup is toward the invasion effort and what

will follow.

The same drive is reflected in war indus-

try and in Army and Navy equipment. A

single firm advertises among its products

motor torpedo boats, steel Diesel-powered

tank carriers, crew-carrying landing boats,

motor-equipment landing boats, armored

combat boats, shore patrol craft, anti-sub-

‘marine motorboats, steel and wood tugboats

and barges, and “amphibious equipment.”

In the air, the Army is training men in

transport gliders which will carry nine fully

equipped soldiers. Another type carries 13

infantrymen in addition to the pilot and co-

pilot. These gliders drop their wheels after

taking off and alight on skids. Experimen-

tation is in progress with a view to picking

up gliders from the air after they have

landed in enemy territory. Cargo planes can

now fly antiaircraft guns, 75's and 105's,

reconnaissance cars, and about everything

except heavy artillery to the combat zone.

They carry troops as well —the Curtiss-

Wright C-46, the “Commando,” holds a sub~

stantial number of fully equipped soldiers.

Among eombat cratt, there are types like

the North American P-51, the “Mustang,”

which are especially designed for hedge-

Hopping and close support of troops. One of

these days we shall see them swooping over

the beaches clearing the way for landing

parties and scouting the terrain further

back.

No one in the armed forces is under any

illusions as to what we shall be up against

when the big push starts. Undoubtedly the.

landings necessary to open a second front in

Europe will be exceptionally difficult. The

Germans have had plenty of time to fortify

the likely spots along the Channel coast and

elsewhere. It is quite possible that published

photographs of German gun emplacements,

batteries, blockhouses, and redoubts have

been deliberately allowed to filter through in

order to give the leaders of the United Na-

tions pause; certainly these steel and con-

crete strongholds are a formidable obstacle.

Some of them appear to be so massive that

it is doubtful whether random bomb hits

from the air would penetrate them. Others

have been dug into the sides of hills so that

they are clearly invulnerable from above.

Certainly there is a big difference between

making a landing in the face of one of these

monstrous constructions, and, for example,

the uncontested or weakly contested Japa-

nese landings in the Pacific.

But does that make the coast secure

against invasion? To answer the question

let us transfer the scene to the United States

and see how it looks from the defenders’

viewpoint. The distance from the resort is<

land of Santa Catalina to the nearest point

on the Southern California coast is exactly

the same as the width of the Straits of

Dover—20 miles. The California coast line

is well fortified, and back of the fortifica-

tions there is a superb network of roads, all

kinds of airports and aircraft factories, and

probably more heavy industry than in some

of the corresponding areas in France. Yet

how secure would the people of Los Angeles

and their defenders feel if Catalina were as

big as England and the Japs were looking

across the channel at the Palos Verdes

Hills? How secure would they feel if the

Japs had air superiority and there was little

or no prospect of taking it away from them

in the calculable future?

The fact is that coastal fortifications have

a definite but limited utility. Their big guns

can be used against shipping, including

naval vessels and transports. As long as

these batteries are active the United Nations

cannot cover a landing with naval guns;

they cannot dock transports in existing har-

bors. But against small and medium-sized

landing boats, barges, and lighters, heavy

artillery is practically useless. The boats

will come in close under cover of darkness

and they will land under smoke screens. The

big guns cannot be trained on the water

close to the shore or on the shore itself. The

defenders will have to rely on light artillery

and small-arms fire to repel the actual land-

ings; thus the situation will be much like

that at points on Luzon where we had such

defenses—and the Japs took them.

Nor is a seacoast a neat geometrical pat-

tern, every foot of which can be covered by

fixed or mobile artillery. Seacoasts were not

designed for the security of the Nazis or of

anyone else. They are complex, irregular

configurations where resolute attackers who

know the terrain can find innumerable coves,

bays, inlets which at a given moment may

be undefended or inadequately defended.

The attackers will naturally avoid the ob-

vious spots; they will know that a difficult

landing site—difficult in the sense of terrain

—may be their best bet because of the ele-

ment of surprise and the unpreparedness of

the enemy.Gaining footholds on the beaches is the

first stage of the invasion. Some of these

footholds will be lost, some will be held. The

second stage calls for reduction of heavy

fortifications at critical points, so that the

third stage—the acquisition of a deep-water

harbor—may become possible. The fortifica-

tions can be reduced. Anything which can

be built can be blown up. If it can't be

blown up at long range it can be blown up

from alongside. The Germans themselves

proved that when they took the multiple

fortress of Eben Emael, near Liege, in the

spring of 1940. These installations were said

to be proof against artillery fire, and in fact

they held out to the end against all the can-

non the Germans were able to train on them.

But they could not hold out against engineer

combat units armed with explo-

sives, advancing under cover of

continuous artillery fire and utiliz-

ing shell craters for cover until

they reached the blind spots close

to the walls of the fortifications.

We have plenty of dynamite and

TNT, and American engineers are

just as tough as German engineers

—maybe tougher. The fortifica-

tions will be assailed from the

flanks by lateral landing parties,

from the rear by airborne troops,

and at a given stage they will face

frontal assaults by new landing

parties. These redoubts are set

back some distance from the shore,

usually on elevations commanding

the sea. The approaches will be

churned up by bombers until the

terrain will look like a series of

gravel pits. There will be plenty of

cover for the later landing parties.

At the same time, naval units may

engage the fortresses in artillery

duels; the close-up attacks already

in progress will compensate for the

advantage shore batteries normal-

ly enjoy over equivalent calibers on

the water. The fortifications will be

subjected to simultaneous assaults

from the air, the sea, and the land.

Where they are immune to normal

vertical and dive bombing, low-fly-

ing aircraft may loose projectiles,

which will bring them in at angles

close to the horizontal, like tor-

pedoes launched at warships.

The defenders will always be

able to repel a single landing at-

tempt. But they will have to con-

tend with multiple raids—perhaps

a dozen or more at a time. Even in

the Dieppe operation, which in

retrospect will seem like little more

than a threatening gesture, the

British were on six beaches at once.

Of course,

some of the multiple raids may be only

demonstrations or feints, but the enemy will

have the pleasure of deciding in each in-

stance whether that particular assault is or

is not the spearhead of a full-scale invasion.

For every one that seems at all menacing

he will have to set his transportation system

in motion to bring up supplies and reinforce-

ments, and use up valuable rolling stock to

redistribute his forces. In the meantime

the bombers will be busy overhead, plaster-

ing communication lines and airports, and

the parachutists will be raising hell in their

own fashion. The enemy will need a great

deal of matériel and large forces in many

places at once, and if they run out of re-

serves at any one point they will face dis-

aster. Once 2 major break-through occurs,

penetrations and envelopments will follow

over a wide front. Those strongholds that

still hold out will be isolated and dealt with

at the invaders’ own convenience.

The losses of the attackers in the early

stages will be huge. At Dieppe the Allied

division which was engaged lost about half

its effectives, in spite of excellent air sup-

port. The forces which make the first land-

ings must expect to sustain losses of this

magnitude. With all the reconnaissance, di-

versionary moves, feints, and harassments

that can be inflicted on the enemy, the prin-

cipal penetrations will just have to be bulled

through. In some of their landings, when

they encountered strong opposition, the Japs

accepted heavy initial losses with equanim-

ity. Americans will certainly not be out-

done in this respect.

In all likelihood, the attacking general

staffs will have a pretty good idea of where

the major break-through will occur, and

their reserves will be disposed accordingly.

But they will have to be prepared to change

their plans at a moment's notice. Much also

will depend on the subordinate commanders.

No two landings are alike and the ability of

the attacking troops to adapt themselves to

conditions quickly and intelligently is just as

important as good staff work and planning.

Landings are always fast-moving situations,

and only dynamic leadership on the spot can

seize opportunities as they arise and utilize

gains to get more gains. And all possible

contingencies will have to be provided for.

It is perfectly possible, for example, that

when the Axia forces are in a desperate po-

sition they will resort to the use of gas

wherever wind conditions permit.

Nor, when we capture a harbor which will

serve in this war as St. Nazaire served in

the First World War, can we expect to re-

ceive it intact with the compliments of the

former occupants. They will wreck it as

completely as they can before they evacuate,

and they will be in a position to do a thor-

ough job. About all we can expect to get is

land, ‘water, and debris. But that will be

enough. The Army's engineer units, and

the special Navy construction detachments,

known as Seabees, will rebuild what has

been destroyed, and add a lot more.

When we have an adequate harbor, the

initial stages of major operations on the

Continent will be over. The logistical prob-

lems accompanying such operations will

then be possible of solution by known meth-

ods. This harbor (or, more likely, harbors)

will be the eastern terminus of a pipeline

which will carry the products of American

war industry to Europe. The Germans will

do their utmost to break the line along its

entire length, and particularly to block its

outlet. It is only prudent to assume that

they will fight as furiously when they are on

the road to defeat as when they seemed to

be headed for victory. This outlet will there-

fore need the strongest air defenses that

modern military technology can devise, for

whatever air power the Germans still pos-

sess will be flung against it. It will have to

be guarded against submarine and surface

attack by nets, booms, and mines. The bat-

teries with which the Germans have ringed

the European coast will have to be dupli-

cated here, Around the invasion area there

will be such a concentration of airfields, AA

and coastal artillery, submarines and anti-

submarine devices, large and small naval

surface craft, merchant ships, transports,

tugs, docks, warehouses, unloading and for-

warding facilities, barracks, troops of all

arms and services, as the world perhaps has

never before seen. But once the machinery

of this gigantic enterprise is in motion the

push into Germany will be in full progress.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Carl Dreher (Article Writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1943-02

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

88-98, 224, 226

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google Digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 142, n. 2, 1943

Popular Science Monthly, v. 142, n. 2, 1943

Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 10.30.35.png

Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 10.30.35.png Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 10.30.46.png

Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 10.30.46.png Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 10.30.58.png

Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 10.30.58.png Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 10.31.17.png

Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 10.31.17.png Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 10.31.32.png

Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 10.31.32.png Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 10.31.58.png

Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 10.31.58.png Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 10.32.07.png

Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 10.32.07.png Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 10.32.22.png

Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 10.32.22.png Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 10.32.37.png

Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 10.32.37.png