-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

How U.S. medical soldiers operate on the battlefield

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

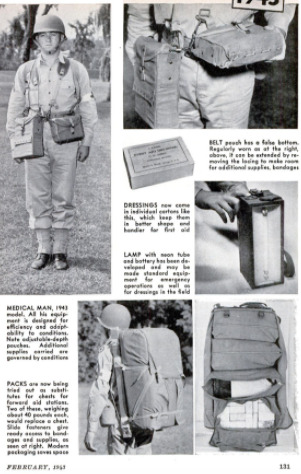

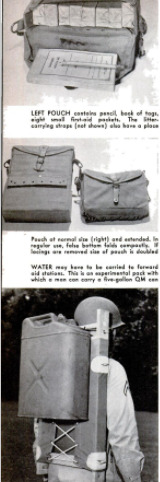

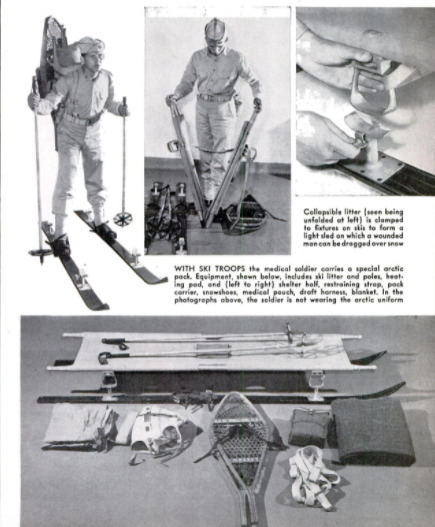

Title: How medical soldiers meet the Blitzkrieg

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

MECHANIZED warfare has brought

new problems to the Army's Med-

ical Department. Even on a rela-

tively static battle front, like those of the

first World War, the task of aiding and

bringing back the wounded is a gigantic

one. In fluid blitzkrieg fighting, with the

tide of battle rolling rapidly over miles of

countryside, the medical men must wage a

blitzkrieg of their own—in reverse.

‘Win, lose, or draw, the Medical Depart-

ment has its hands full. When things go

badly, it may find itself responsible for 25

percent of the total personnel engaged in a

given sector. When things go well, the per-

centage of wounded is likely to be less, but

the very success of the operation introduces |

new difficulties. A clearing or sorting sta-

tion for the wounded which was located six

miles behind the front at the beginning of

the attack may be 20 to 30 miles behind |

after a few hours. Yet the medical units are

bound to keep up with the movement some-

how, for time is precious. The sooner a seri- |

ously wounded man can be picked up, given |

first aid, and evacuated, the better his

chances of survival. The farther back he

goes the more comfortable he can be made

and the more adequate the treatment which

can be given him.

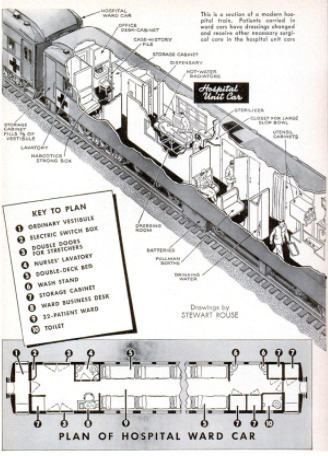

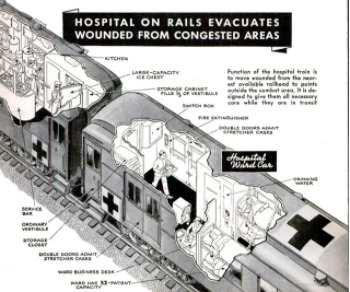

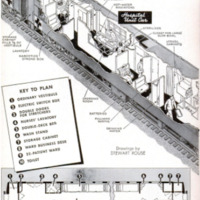

The illustration at left below is a sche-

matic representation of our Army’s current

arrangements for handling the wounded.

From right to left, the sketch shows the

combat area between the battle front and

the nearest railhead. Evacuation is carried

out in stages or echelons. The zone between

the battle line and the collecting station or

assembly point, normally about 1 1/2 to two

miles in depth, is called the first echelon. In

this zone all service to the wounded is ren-

dered by medical personnel attached to the

line units. The second echelon begins at the |

collecting station and extends to the clear-

ing station five to eight miles behind the

line of departure. This is a divisional zone,

in which service is rendered by the division

medical units. Still farther back, in the

third echelon, the medical units attached to

an army, which consists of several corps and

divisions, take over the casualties.

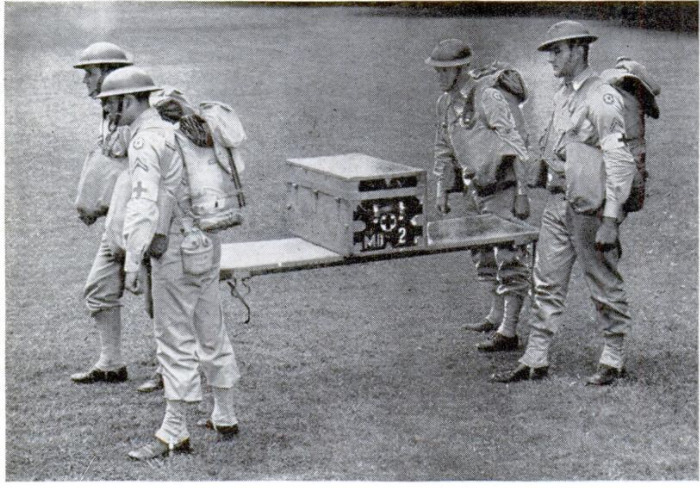

In the battle area itself, essential first aid

is given to the wounded, under whatever

cover can be found, by first-aid men at-

tached to the companies in combat. The

next step is to get the wounded back to bat- |

talion aid stations some 300 to 500 yards be-

hind the front line. These field dressing sta-

tions usually afford shelter from rifle fire,

but not from chance artillery hits. Every

effort is made to locate them so that the

wounded can be brought in by stretcher-

bearers under some sort of cover, as behind

a hill or ridge, and if at all possible be |

evacuated, when night falls, in vehicles

rather than on foot. The normal comple-

ment of the aid station is two medical offi-

cers and seven enlisted men trained in han-

dling injuries. Here efficient temporary

dressing of wounds is possible and morphine

is available,

If the battalion moves forward the station

moves with it, the patients already deposited

being left with medical attendance until

they can be brought back, by ambulances or

stretcher-bearers, to the collecting stations.

Each of the collecting stations is fed by sev-

eral battalion aid stations. Like the latter,

the collecting stations move forward with

the combat forces. The collecting stations

are essentially intermediate medical bases

where patients are examined, sorted, and

prepared for evacuation to the clearing sta-

tions. Between the collecting and clearing

stations an ambulance shuttle service is

maintained, During the night the ambu-

lances may be able to go all the way up to

the battalion aid stations. When this is

feasible the wounded are far better off, for

it is in the first echelon that the worst bot-

tlenecks occur.

The division clearing station is usually

out of medium artillery range, and on a

good route to both

the front and the rear. Here a more careful

sorting of casualties takes place. Some may be

found fit for duty and returned to the front.

Others, who require operative treatment, are

taken care of by a mobile surgical unit at-

tached to the clearing station. Thence the seri-

ous cases are sent back to the evacuation hos-

pital, which normally is located at a railhead or

airport where hospital trains or planes are

available to take them out of the combat zone

as soon as they are fit for the journey. Less

serious injuries are treated at a convalescent

hospital in the same neighborhood. After dis-

charge these are sent to a replacement depot

and returned to the front.

‘The foregoing will give the reader some idea

of the transportation difficulties involved in

giving first-aid and evacuation service to the

wounded. Yet it presupposes a relatively slow-

moving tactical situation in which the disabled

man has to be carried only a few hundred yards

on a stretcher before he is laid on a table be-

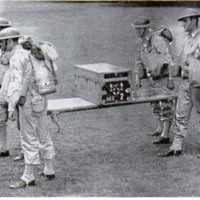

fore a medical officer. Suppose, however, that

the injured soldier is in a tank operating with

an armored division. There is no room for

company aid men in tanks. Members of tank

crews are trained to take care of their own

emergency cases, using vehicular first-aid kits

carried in the tanks. The company aid men

follow the advance in motor vehicles and col-

lect casualties along a central axis of evacua-

tion. They then get their patients to the rear

from prearranged rallying points. Half-track

armored vehicles which have carried armored-

division infantry behind the tanks are often

used for this purpose. These half-tracks are

equipped with litter braces so that they may

be used as improvised ambulances.

‘Who are the men responsible for the health

of the millions of Americans already in the

Army and the millions who will soon join

them? Where do they come from and how are

they trained? Some civilians have an idea that

most of the Medical Department's personnel

consists of physicians. The fact is that out of a

total strength of 125,000 before Pearl Harbor

(current figures are restricted), only 183,000,

or a little more than 10 percent, were offi-

cers, and not all of these were physicians.

In World War I the Medical Department

numbered 400,000—an army within an army.

There is nowhere near that number of li-

censed physicians in the United States. Ob-

viously, while physicians provide the mili-

tary and scientific leadership in the Medical

Department, the bulk of the routine work

must be done by officers other than Medical

Corps physicians. This calls for a gigantic

training program.

Today, the Medical Department is operat-

ing four medical replacement training cen-

ters and nine special-service schools. Men

are assigned to the schools on the basis of

civilian occupa-

tion and aptitude as determined by classifi-

cation tests. The schools have a combined

yearly capacity of about 160,000 trainees—

35,650 basically trained medical soldiers can

be delivered to medical units or installations

every 10 weeks.

Medical transportation is a vital factor,

not only in saving the lives of sick and

wounded men, but in maintaining the mo-

rale of the whole Army. Once a unit gets

into action, good morale implies the indi-

vidual soldier's willingness to die to gain a

vital objective. But the soldier knows that

he may neither escape unscathed nor be

killed; he may be wounded. In that case

he wants to be taken out of there—fast. If

he has confidence in the Medical Depart-

ment’s ability to move him with the least

possible delay, and to give him every pos-

sible chance for life, he will be a better

fighting man.

~The ideal ambulance will go almost any-

where, provide a comfortable ride for the

patient, and go as fast as is consistent with

safety. The latest Army motor ambulances

fill these specifications adequately and are

cheap to build. The body is mounted on a

standard Army half-ton chassis with four-

wheel drive. The gross weight with a 1,500-

pound “payload” is 6,670 pounds, and the

speed is anything from 2 1/2 to 55 m.p.h. on

roads. The vehicle can go cross-country if

the terrain is not too rough. The body is of

20-gauge steel, thermally insulated, and hot

water from the engine maintains a 70-de-

gree temperature when the outside tempera-

ture is below zero. A fan changes the air in

the body once a minute. Rear doors are 58

inches wide and 47 inches high to facilitate

loading. The springs are inclosed in metal

covers to prevent rusting. An ambulance of

this type will accommodate four litter pa-

tients or seven sitting patients. The jeep

offers excellent possibilities in forward areas

as an ambulance with very slight adjust-

ments.

he Army also has a very light horse or

mule-drawn ambulance (1,130 pounds) with

an automobile body and low-pressure tires.

This will hold four men in litters or five

seated. At the other extreme there is an

ambulance of bus type, holding 12 litter pa-

tients or 20 sitting patients. This is equipped

with front-wheel drive for speeds of 21 to

70 m.p.h., and although designed for roads

can go cross-country when necessary. Plans

have also been made for converting ordinary

suszes into ambulances if resuired. It is

possible that future ambulances will be

lightly armored for protection against

small-arms fire.

Air ambulances will be used by the Army

as far as possible. The War Department re-

cently announced the formation of an Air

Evacuation Group (Medical) to evacuate

sick and wounded soldiers at top speed. It

is estimated that a trip which might take 18

hours over difficult terrain in a vehicular

ambulance can be accomplished in one hour

by plane. The planes to be used are large

transport or cargo ships which will bring in

supplies and take out the wounded. They

will be fitted with racks for standard Army

stretchers, surgical and blood-transtusion

facilities, oxygen masks, heating pads, and

other equipment for 40 patients. Each plane

will carry a flight surgeon, a nurse, and a

Medical Department enlisted man who has

been specially trained for evacuation of

wounded by air.

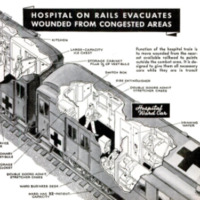

To do his best the physician or surgeon

needs adequate laboratory and operating fa-

cilities. In war the surgery and the labora-

tory have to go to the patient, not the other

way around. To design and build a rolling

surgical hospital, with its own water and

power supply and facilities for heating, ven-

tilation, sterilization, and all the other re-

quirements, is a problem which at first

seems insoluble. But the Army has de-

veloped such hospitals in both self-propelled

and semitrailer types.

The methods of treatment used in the

Army's mobile and fixed surgical hospitals

are the latest and best. The sulfa drugs

occupy a prominent place in military sur-

gery these days, and the mortality figures

leave no doubt as to their efficacy. In World

War I the mortality from perforating

wounds of the abdomen was 80 percent, The

victim had one chance in five to live, Now,

on the basis of experience in the Philippines

and at Pearl Harbor, Maj. Gen. James C.

Magee, Surgeon General of the U. S. Army,

reports that such wounds are seldom fatal,

and a large number of the men who sus-

tained serious wounds have already re-

turned to duty.

The sulfa drugs are a vital element in the

remarkable results that Army surgeons are

getting in wound therapy, but only one ele-

Last we may consider What the Medical

Department puts first—the prevention of

disease. The air lines talk about preventive

maintenance. They got the term from pre-

ventive medicine. In every war the enemy

most to be dreaded is disease. Disease kills

more men than wounds. The health of the

Army so far has been excellent. This is not

mere luck; if it were we could not rely on.

its continuance.—CARL DREHER.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

William W. Morris (Photographer)

-

Carl Dreher (Article Writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1943-02

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

126-133, 228, 230

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google Digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 142, n. 2, 1943

Popular Science Monthly, v. 142, n. 2, 1943

Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 15.08.38.png

Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 15.08.38.png Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 15.09.11.png

Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 15.09.11.png Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 15.09.21.png

Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 15.09.21.png Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 15.09.37.png

Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 15.09.37.png Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 15.09.50.png

Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 15.09.50.png Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 15.10.06.png

Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 15.10.06.png Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 15.10.45.png

Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 15.10.45.png Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 15.11.20.png

Schermata 2022-02-20 alle 15.11.20.png