-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Kaiser builds a new ship

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: What happens when Kaiser builds a ship

-

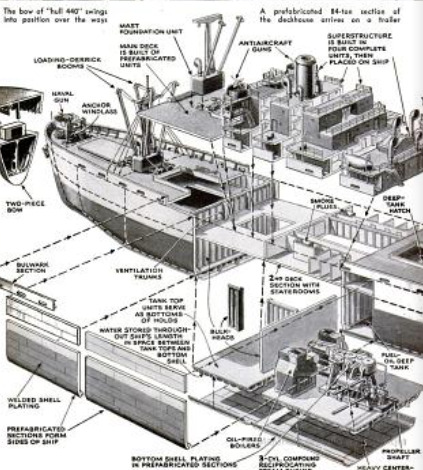

Subtitle: A jigsaw puzzle of steel with a quarter of a million pieces and 97 prefabricated sections, form a new vessel fro victory

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

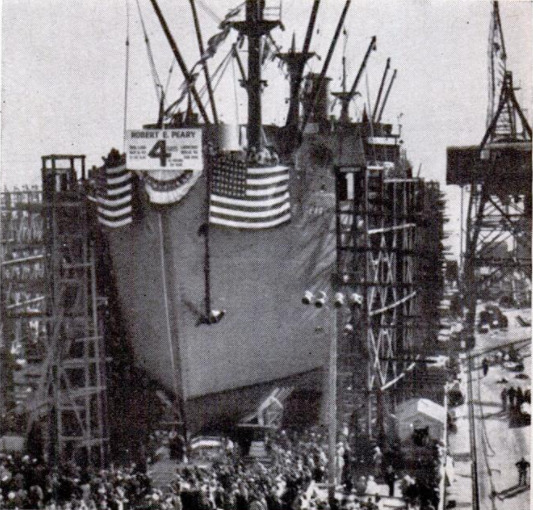

WHEN the 10,500-ton Robert E.

peary on November 12, 1942,

slid down way No. 1 of Henry

J. Kaiser's Richmond shipyard after

being on the ways only four days, 15

hours, and 26 minutes, it did more

than set a world's record in speedy

shipbuilding. It set records in pre-

fabrication, labor-management co-op-

eration, and Yankee ingenuity in getting a |

fast job done well. Prior to the launching of

the Peary—called “Hull 440” while in con-

struction—the Richmond builders had been

averaging a keel-to-launching time of 57 days |

per hull, which they had subsequently lowered

to 42 days. They were feeling pretty proud

of themselves when word came that the Ore-

gon shipyards had launched a hull in 10 days

and had delivered 11 ships that same month. |

Kaiser's engineers hitched up their pants and

decided they’d do something about that. They

started by asking questions of welders, rig- |

gers, pipefitters, shipfitters, draftsmen, and

machinists—and the answers came back in

hundreds of ideas—rigs, jigs, gadgets, devices, |

and suggestions which showed that the workers |

not only knew their business but

that they were willing to work for a

new record. Take the welders, for

instance. When volunteers were

called for, a dozen women welders |

threatened to quit unless they were

included. They and dozens of men |

went to work with arcs blazing, and

by the time the hull was laid, 152,000

feet of weld had been completed on

the assembly tables—50,000 more

than on previous hulls—and only

57,800 remained to be welded on the

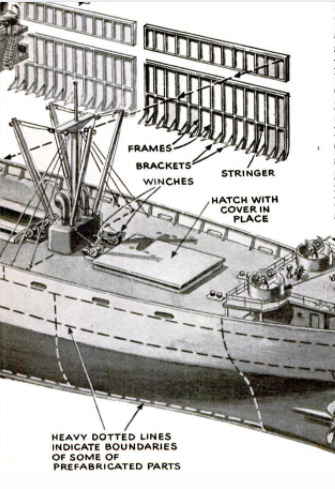

ways. Riggers then found they had

fewer lifts to make because prefabri-

cated sections were more complete.

So they set about saving hundreds of

man-hours by moving 84-ton deck-

houses and 70-ton bulkheads nearer |

the ways to have them right at hand

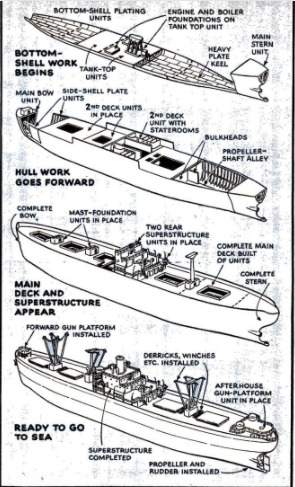

the instant they were needed. Pre-

fabrication reached such a high that

when the main unit of the 440's

deckhouse was swung into place with

giant cranes, it was complete down

to electric clocks and inkwells.

Approximately 250,000 individual

items went into the building of Hull

440. But by the time the prefabrica-

tion boys had finished their work on

the assembly tables, only 97 giant

sections needed to be lifted on to the

ways. The huge keel called for the

laying of merely six main sections.

Eighty percent of the 23,005 rivets

used were driven home on the as-

sembly tables. And on the bilge and

forepeak, 18 gangs of five men each

worked ‘round the clock to finish

their job before the keel was laid.

The marine machinists did their

job, too. They had the 135-ton en-

gine in place 12 hours after the keel

was down, and in another 36 hours

they had it ready to run.

Before shipyard workers can do

their job, they must have the mate-

rials—and they must have ‘em when

they need ’em. To insure that they

get them, Kaiser employs a staff of

what he calls expediters. Ingenious,

resourceful, and aggressive, these

energetic men scamper all over the

country, busting bottlenecks wide

open as they run. It is this kind of

teamwork that has reduced ship-

building time from years to days.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Stewart Rouse (Illustrator)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1943-03

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

64-66

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google Digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 142, n. 3, 1943

Popular Science Monthly, v. 142, n. 3, 1943