-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

New training and equipment for seamen security

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: Cheating Axis torpedoes

-

Subtitle: Sound training and good equipment now bring shipwrecked seamen back to port

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

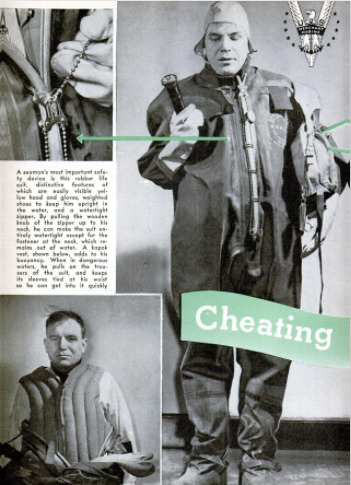

IT WAS all over before you could say “All

hands on deck—man the lifeboats!” One

minute Marty was standing watch on the

graveyard shift, wondering if he really saw

a streak of foam creasing the inky waters—

the next, the whole ship heaved and shud-

dered and, with a terrible splintering crash,

split in two.

In a matter of seconds, or so it seemed

to Marty, the deck he stood on was awash

and he was going under. Worse yet, the

lifeboats up forward were lost, and Marty's

hand had been badly crushed by a hurtling

piece of deck plate. But he was in very

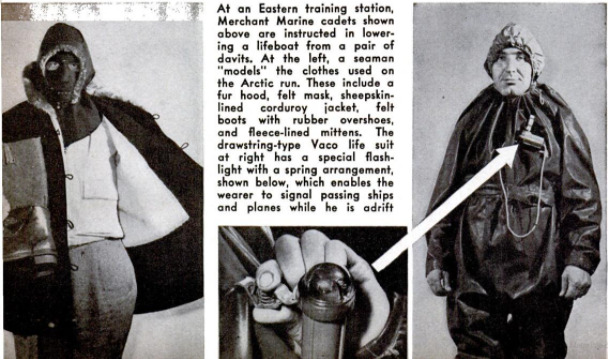

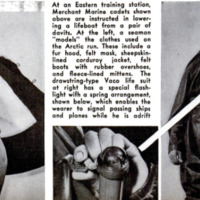

little danger. For one thing, he had a new-

style kapok vest strapped tightly around

his torso, and, in addition, his rubber life

suit was half on, with the sleeves tied

around his waist. In practically nothing

flat he had his arms inserted in the sleeves

and the helmet adjusted over his head. One

yank with his good hand zipped the slide

fastener shut up to his neck. His water-

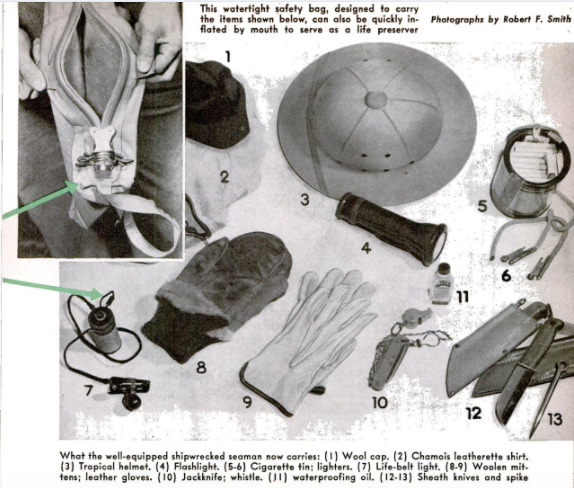

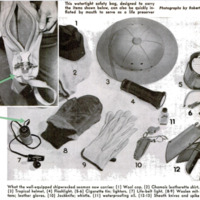

tight emergency safety bag, full of valu-

able gear, was right beside him, and in an-

other moment he had it hanging over his

shoulder. Had he been caught without any

other equipment, this little bag would have

saved the day for Marty, for there was

enough air trapped in it to support the

weight of two m a in the water.

‘What subsequently happened to this typi-

cal seaman is now a common story among

the gallant men of our merchant marine.

‘With his air-filled .fe suit, his inflated

bag, and his kapok vest, he had buoyancy

to spare, and he wasn't pulled down very

far by the suction from the sinking boat,

nor even by the davit guy wire that mo-

mentarily coiled around his boots. As soon

as he shot to the surface, he kicked himself

upright, and the next moment he was flash-

ing the red signal light clamped to the

chest of his rubber suit. Some of his ship-

mates who had managed to lower away one

of the life boats aft were attracted by the

flickering light, and soon had hauled him

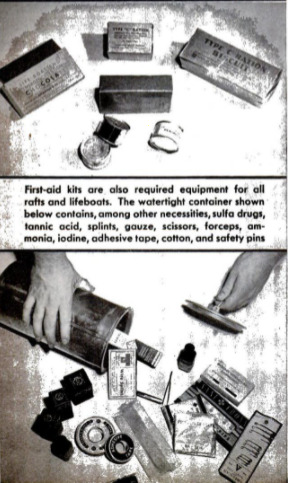

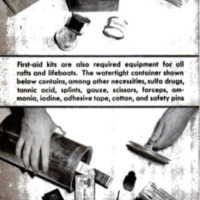

into their boat. Here there was an ample

stock of sulfa drugs and other medicinal

supplies in the emergency first-aid kit, and

Marty's hand was carefully attended to.

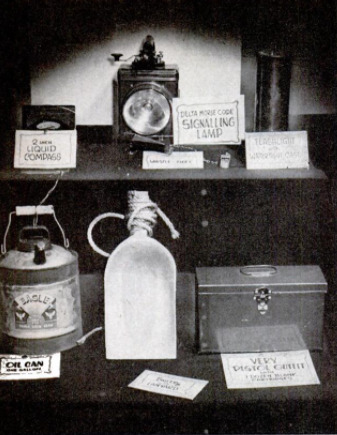

Even better, the boat was equipped with

a portable radio receiving and transmitting

set. The ship's radio operator had gone

down with the vessel, but there was no

difficulty in operating the radio, since it

had an automatic signal which flashed re-

peated SOS’s over the international-distress

wave length to all ships at sea and coastal

listening posts. This distress signal was

picked up by a near-by Coast Guard sta-

tion, which speedily dispatched a rescue

boat. There was no trouble in finding the

lifeboat a few hours later, because Marty's

comrades kept shooting up brilliant red

parachute flares from their signaling gun.

Today, a little more than a year after

the opening shot of the war, the United

States merchant marine has become expert

in meeting all emergencies at sea, and is

being equipped with a host of lifesaving

devices which bid fair to make it the safest

merchant fleet in the world.

How this safety streamlining was accom-

plished is a story of close co-operation be-

tween the Navy, the Coast Guard, the

Maritime Commission, the War Shipping

Administration, and hundreds of sailors in

the maritime unions-—men like Marty and

his mates who came back from sea with

recommendations based on first-hand ex-

perience. Early in the war, the National

Maritime Union, for example, drew up a

safety program designed to save lives,

ships, and cargoes from avoidable loss. In-

cluded in this program were urgent pleas

for better loading of ships: the proper

provisioning of lifeboats; the installation on

all merchant ships of lifesaving suits, rafts,

and defensive arms; the reconditioning of

quarters to accommodate Navy gun crews;

compulsory lifeboat and fire drills on every

boat before leaving port; the keeping of

lifeboats swung out on their davits at all

times; the establishment of an adequate

coast patrol through the requisitioning of

small private craft; the organization of

safety committees aboard all ships; and a

thorough training program for new men.

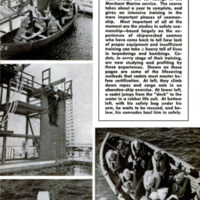

Government experts, engaged in _elabo-

rate research on their own, listened care-

fully to the men who man the ships and in

many instances adopted their suggestions.

Government agencies then swung into ac-

tion by drastically tightening the regula-

tions covering equipment and behavior on

board merchant vessels. Local Merchant

Marine inspectors in every port, operating

under the Coast Guard, Went over every

ship from stem to stern, checking the safety

equipment and supervising the installation

of new gear. The Division of Training of

the War Shipping Administration, under

Telfair Knight, director of the division,and

Captain R. R. McNulty, assistant director

and supervisor of the Merchant Marine

Cadet Corps, has set up 13 centers for

the training of thousands of men. Some of

these centers are cadet schools which are

training men from civilian life and seamen

up from the fo'csle for both licensed and

unlicensed ratings in the Merchant Marine.

Others, like the huge Sheepshead Bay Mari- |

time Training Station at Oriental Point,

N. Y., are preparing men to be stewards,

deck "hands, and boiler-room apprentices,

Tn every school a strenuous Safety Seaman. |

ship Program has been instituted, |

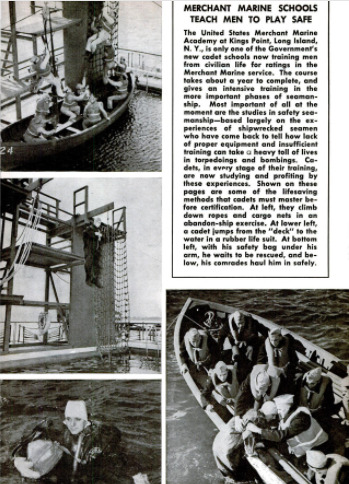

The United States Merchant Marine

Academy—Ilocated at Kings Point, L. I, on

the luxurious grounds that were formerly

the estates of Walter P. Chrysler, Nicholas

Schenck, and the late movie star, Thomas |

Meighan—is typical of the Government's

cadet training centers. Entrance require-

ments are every bit as tough as the Navy's.

Only high-school graduates of good char-

acter, and who can pass stiff physical and

intelligence tests, are admitted. Cadet offi-

cers, taken from civil life, receive 10 weeks

of preliminary training, then spend six

months at sea, and finally return to school

for six to eight months of additional in- |

struction. Their classes cover naval science,

seamanship, navigation, cargo loading, ship

construction, lifeboat certification, and a

heavy dose of Safety Seamanship—in other

words, a course of study that runs the

whole nautical gamut.

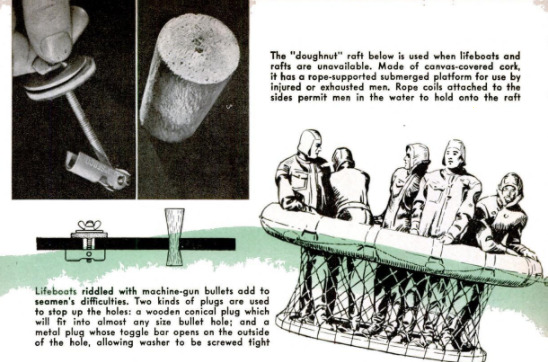

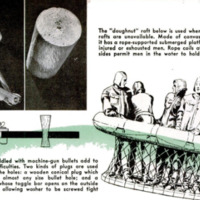

Before certification, the cadets go through

a four-hour drill which simulates the actual

conditions of a vessel under fire. This is

the acid test, and it takes real proficiency

to survive it.” Some of the men, designated

as casualties, are lowered into lifeboats and |

given first-aid treatment while the crew

is pulling away

from the ship. Then the lifeboatman in |

charge makes a thorough inspection of the |

boat. Once he has ascertained that it is

seaworthy—in an actual sinking he would |

have to supervise the plugging of all holes |

caused by machine-gun strafing or any |

other mishap of battle—he checks all provi- |

sions, distributes his men to the various

watches, and assigns duties to the whole

crew. He then appoints his next in com- |

mand and confers with them, studying the

pilot chart to determine the most suitable

point of land to head for.

When all these preparations have been

made and a course charted, the log must be |

written up and orders given. Now the rou-

tine life begins, and a tough life it is, as |

taught by the Academy instructors. Cadets |

learn that they must at all times maintain |

the strictest discipline to bolster flagging |

spirits—every man must be constantly oc. |

cupied, for idle minds are prey to fear and |

despair. No smoking is allowed on lookout, |

and talk is cut down to a reasonable mini-

mum; a man with his eyes peeled for a

passing ship or plane, or for land, must not

be distracted from his job. Most ticklish

task of all, and the most exacting, i to |

figure out the rationing of provisions. This |

depends partly on climatic conditions: more |

water is needed in the tropics; less water

and more hard provisions to provide body

warmth in northern latitudes. For the rest,

the time period over which supplies must

last is cautiously estimated by doubling the

number of days it will take to reach the

nearest point of land under favorable pre-

vailing winds. |

One of the commander’s first duties is to

call in all personal supplies before the ra-

tioning system is laid down. This rule is

nowhere so essential as in the control of

cigarettes. Smoking not only keeps a man's

spirits on even keel in the grimmest of

circumstances—it also cuts down his ap-

petite appreciably, and thus makes emerg-

ency rations go that much farther. Archie

Gibbs, twice-torpedoed deck hand who spent

four days as a prisoner aboard a German

sub, says “guys have been lost when they

stood up in the boat, said they were going

to mosey across the street for a smoke, and

stepped over the side.”

By the time the war comes to an end,

ours will be a merchant marine of seasoned

men, for the Government is doing every-

thing possible to make sure that men now

going to sea in American ships will be back

to finish the job.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Bernard Wolfe (Article Writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1943-03

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

84-89, 214

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google Digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 142, n. 3, 1943

Popular Science Monthly, v. 142, n. 3, 1943

Schermata 2022-02-21 alle 15.39.12.png

Schermata 2022-02-21 alle 15.39.12.png Schermata 2022-02-21 alle 15.39.30.png

Schermata 2022-02-21 alle 15.39.30.png Schermata 2022-02-21 alle 15.39.46.png

Schermata 2022-02-21 alle 15.39.46.png Schermata 2022-02-21 alle 15.40.03.png

Schermata 2022-02-21 alle 15.40.03.png Schermata 2022-02-21 alle 15.40.17.png

Schermata 2022-02-21 alle 15.40.17.png Schermata 2022-02-21 alle 15.40.22.png

Schermata 2022-02-21 alle 15.40.22.png Schermata 2022-02-21 alle 15.40.50.png

Schermata 2022-02-21 alle 15.40.50.png Schermata 2022-02-21 alle 15.40.58.png

Schermata 2022-02-21 alle 15.40.58.png