-

Titolo

-

Studios on the Battlefield

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Studios on the battlefield. Daredevil Cameramen Shoot History's Most Photographed War

-

extracted text

-

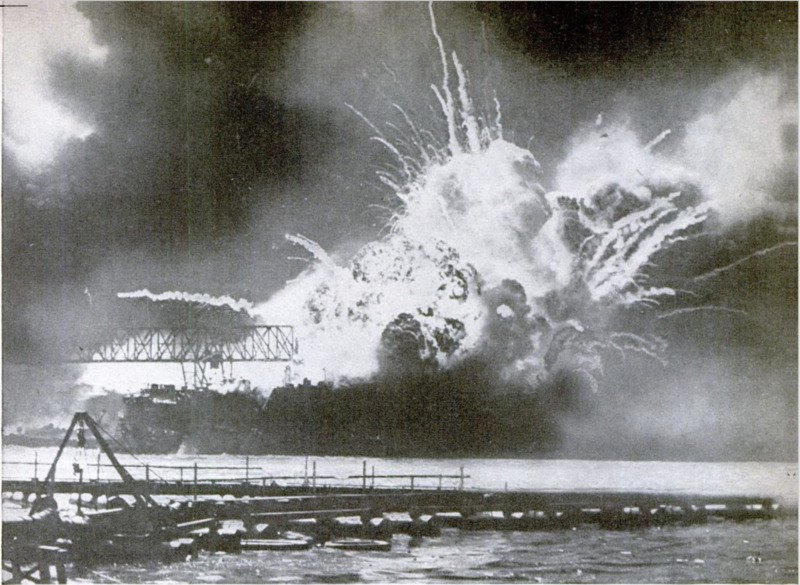

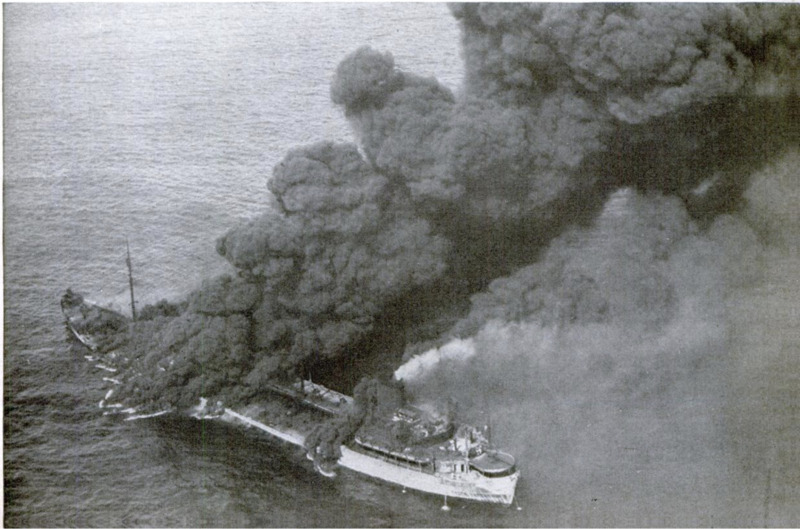

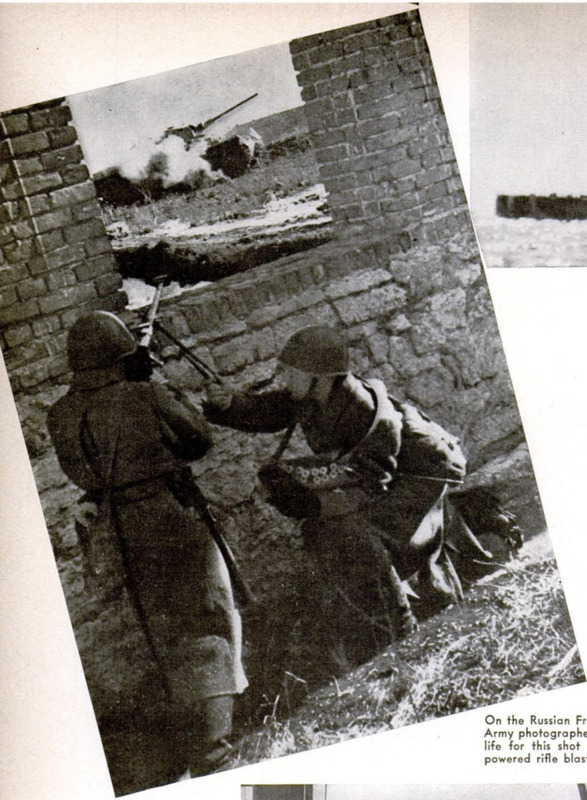

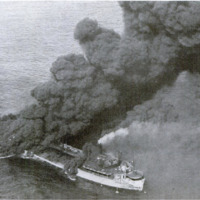

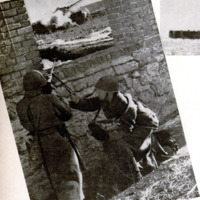

CAMOUFLAGED machine-gunners wriggle to the edge of a thicket and peer into a clearing below. We see their faces at close range—strong, alert faces with the same purposeful glint as their guns. Then we get a view of the other side of the small valley where a second machine-gun detachment is crouching among the trees. The men strain forward, fingering the triggers of their guns. A big, heavily armed reconnaissance car crawls into the clearing, and is immediately enveloped in a crisscross of machine-gun fire. Its occupants slump. Several tumble to the ground. The car jerks to a halt, and the two ambush parties take over. The image fades; another “war picture” has ended. But this is the real thing. Thanks to some unsung newsreel hero, we have glimpsed a distant battle scene from the safety of an air-conditioned American theater. We pick up our morning newspaper. Black headlines tell of a new offensive, and there before our eyes rises the smoke of battle in a four-column picture. A photographer was on the job. A big warship is attacked and battered into a flaming mass of steel. There it is before us. We see our own tanks blasted and blasting the enemy; we see our

own planes roar over their targets; we see enemy planes attack and fly away, or fall smoking from the sky. Lensmen inside and outside of our armed forces are risking their lives daily to show us what's going on. This is the most photographed war of all time. In the first World War we were lucky to get views of our troops marching off to war, of our convoys sailing, of generals meeting far behind the front, of Y.M.C.A. doings and Red Cross parties. Once in a while we saw a picture of some shell-shattered buildings, but never did we get a picture of actual combat. That last touch of realism was saved for the fighting forties. Behind the film front of World War II is a story of courage and cunning, skill and sacrifice. Hitler was the first world leader to discover in films a new weapon of war. Some of our cameramen saw his plan in| embryo while they were covering the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin, They stumbled upon it in looking up German cameramen they had known in America. Inquiries brought out the amazing fact that 120 of the Reich's best lensmen were living at the same address under military conditions and taking orders from Hitler's official cameraman, Leni Riefenstahl. These

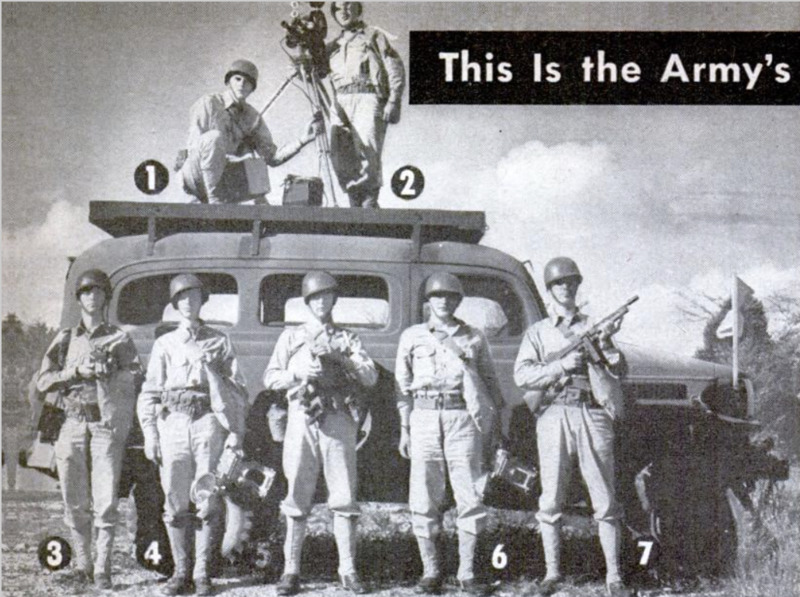

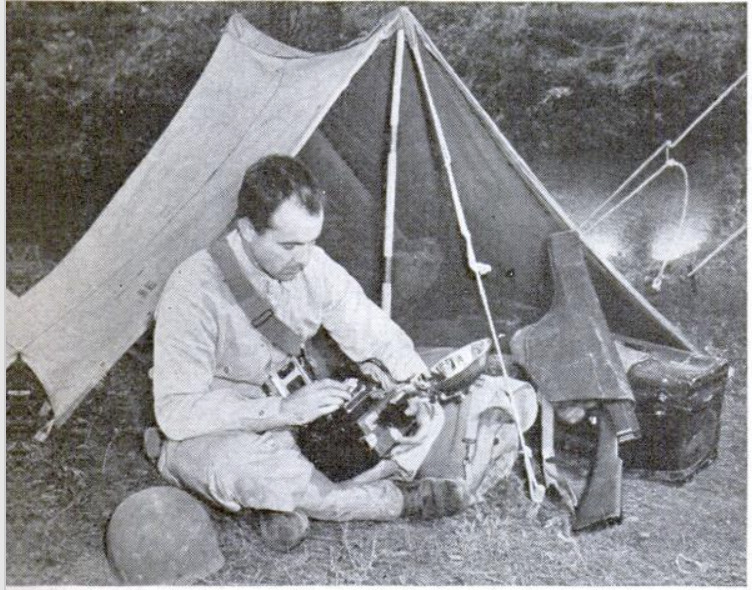

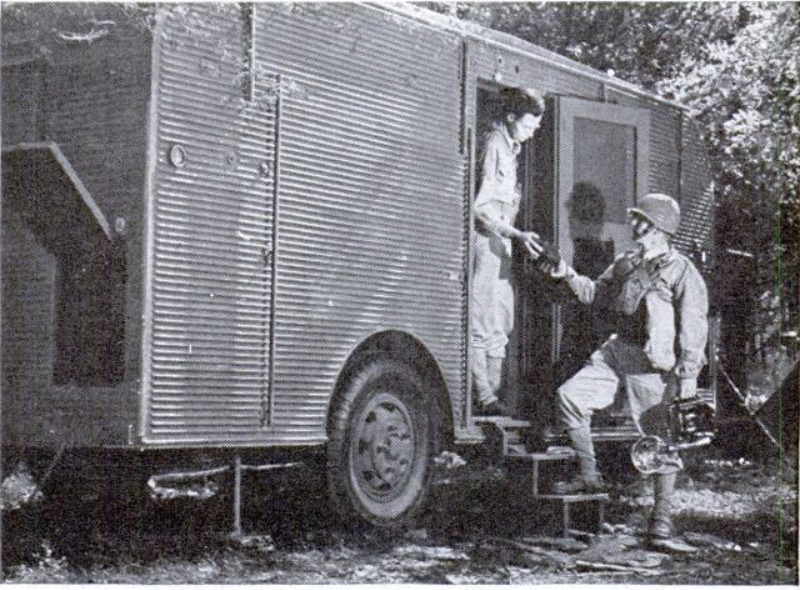

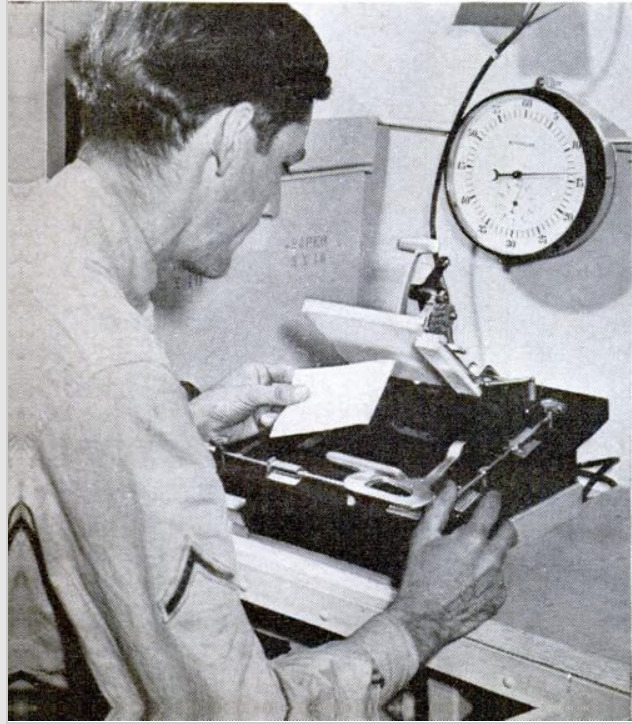

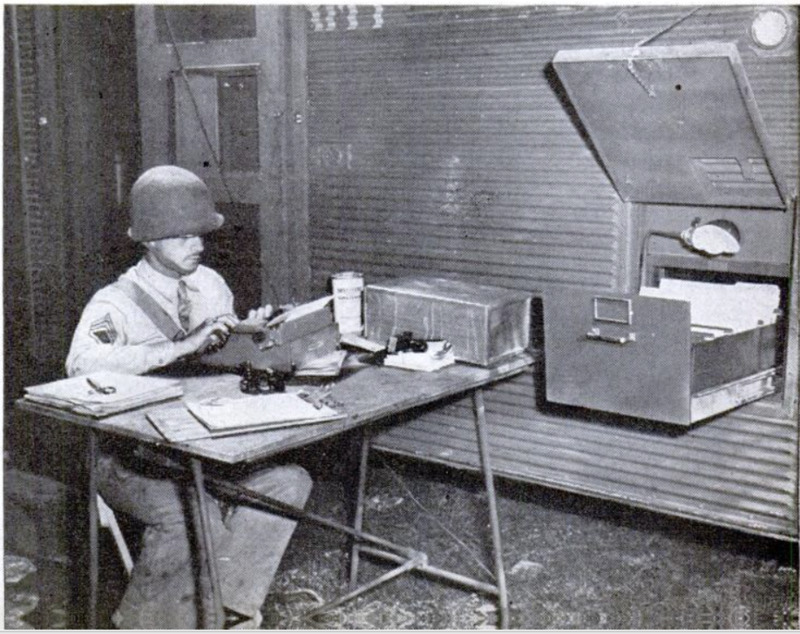

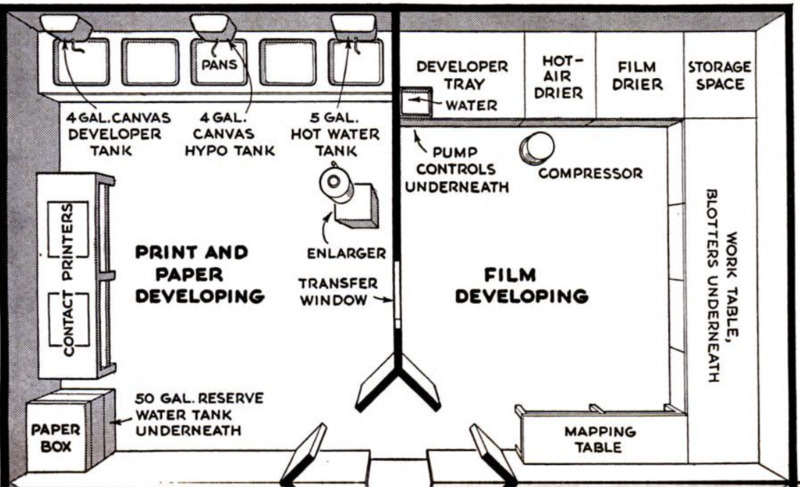

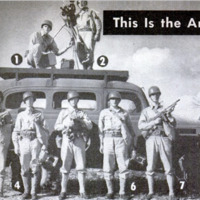

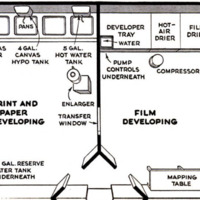

Germans formed the nucleus of the force of 500 cameramen that Hitler sent to the front when the war started. Great Britain was slow to realize the importance of the new weapon with which Hitler began terrorizing neutral countries and emitting propaganda barrages. While the Germans were shipping off thousands of feet of film laden with sadistic, nerve-freezing attacks of dive bombers and tanks, the British were content to distribute films of troops behind the lines in France, drilling and playing football. When Britain decided to send an expedition to Norway, only one cameraman was permitted to go along—one man to film a continental expedition of the British Army—whereas 32 cameramen had been assigned to cover the Grand National Steeplechase! But Britain learned—and so did the United States. Today our film coverage of the war has surpassed that of the Nazis. In the air, on land, and on the high seas, our cameramen and photographers are in action, and their films are making a thrilling record, an astounding informative pattern of war for our military leaders and our citizenry. Soon after we got info the war, American newsreel and news-picture agencies worked out their plans. Co-operating closely with the War and Navy Departments, the agencies formed pools to receive and distribute not only the films of their men in the field but also those of the growing corps of Army and Navy photographers and cameramen and those of our Allies. They arranged with Washington to send men to all the far-flung fronts to which our fighting men were going. The pools were set up in New York— the Roto Pool (for still pictures) and the Newsreel War Pool. ' Now into the two pools go all photo material of the war for immediate public showing, once the censors have given the green light. Members of the pools share the expenses of keeping men at the front and divide coverage equally. Charter members of the Roto Pool are Acme, International News Photos, The Associated Press, and Life Magazine, each of which has seven photographers in the field. But the pool is open to any photo agency, newspaper, or magazine meeting the requirements, chief of which is to share coverage expenses. Insurance is one of the most costly items, amounting to as much as $1,200 a year per man. Other expenses, including equipment, supplies, living costs and uniforms, bring the total to about $80,000 a year for each member—a small price for the superb pictures obtained. Civilian war photographers and cameramen are given the same rating as war correspondents, once they are assigned to a combat unit. That is to say, they enjoy the privileges of officers. They must be accredited in Washington before they are eligible for duty abroad, and they lose their civilian status to the extent at least that they are subject to the orders of the military or naval command to which they are attached and must accompany it into battle or wherever it goes, unless ordered to do othetwise. Officers’ uniforms, minus all insignia except an identifying brassard. But in action they share the dangers of both officers and enlisted men. It is remarkable that only a few have been on the casualty lists. Five newsreel companies—Fox Movietone, Pathe, Paramount, Hearst's “News of the Day,” and Universal—comprise the Newsreel War Pool. Each has two cameramen on the fronts of the world, with others available if and when Washington opens new pool areas. All newsreel and still-picture films are subject to stiff censorship regulations, the authorities here and abroad keeping a sharp eye out for anything that might give aid or comfort to the enemy. The usual procedure in the case of stills is for censorship to begin with the military or naval commander in the field, thence to the fleet or zone commander and then to Washington. Newsreels generally are sent directly to Washington for review. Hitler may have been the first to employ films as a weapon of war, but our own military leaders have made up for lost time. Special training schools have been established to prepare cameramen and photographers for the fighting fronts. One of the most ambitious Army projects has been the establishment under the Signal Corps of new self-contained, mobile photo assignment units, with cameramen, photographers, laboratory men, and assistants equipped to record front-line action. From their welded platform atop an Army carry-all cameramen, protected by the Tommy gun of their driver, grind out scenes of battle of utmost importance to the military leaders—and of absorbing interest to the public when permitted by the censors to supplement the films in the war pools. The Navy, too, has realized the benefits derived from newsreels and photographs of actual combat. Some of the most striking pictures to come out of the war zones are the work of Navy lensmen. To expedite the training of naval cameramen, the newsreel companies have opened their doors to Navy men, sharing with them their professional secrets and experience. The classes are held at race tracks and fires, ship launchings and weddings. The idea is to give the Navy men practical experience by having them accompany a professional cameraman on regular news assignments and film the same events that he does. The newsreel producer compares the films and sends a critique to the Navy Department.

-

Autore secondario

-

Jack O'Brine (writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1943-03

-

pagine

-

108-113, 216

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google Digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)