-

Titolo

-

America's best tanks

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: Why America's tanks are the world's best

-

Subtitle: Guns, speed, armor, durability - this have given us the lead on the proving grounds of the war

-

extracted text

-

THE battlefield value of a tank depends

on three qualities: the power of its guns,

its ability to take those guns where they

can do the greatest possible damage to the

enemy, and its mechanical durability.

In the fighting on the African desert

which was climaxed by Rommel's rout,

American light and medium tanks lend-

leased to the British—a few of them han-

dled by American crews—consistently out-

matched German tanks of their classes in

all of these qualities. Our 13%-ton light

tank proved itself to be the hardest-hitting,

fastest, and mechanically most dependable

light tank on the vast and dangerous prov-

ing ground. Our M-3 medium tank, which

the British call the General Grant, outshot,

outspeeded, outlasted, and generally outper-

formed the German 18-ton Mark III and

22-ton Mark IV mediums which had been

more than a match for the British Valen-

tines and Matildas of the same respective

weights.

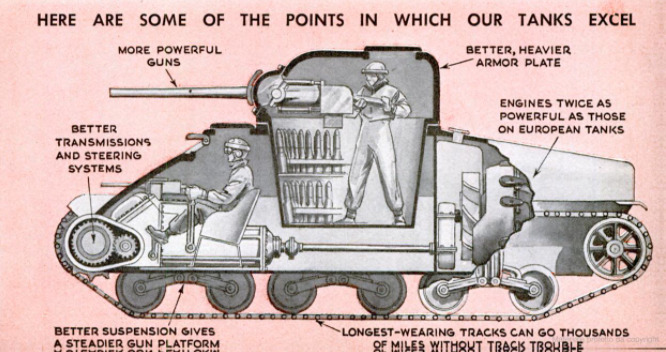

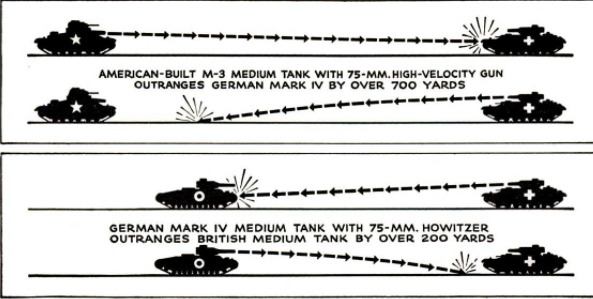

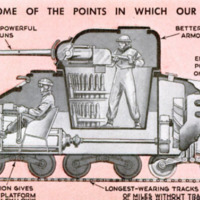

As soon as they got into action, the Amer-

ican medium tanks proved that they had

more powerful guns than the German

fighting vehicles. They also proved to be

much better than the German medium

tanks for the job of carrying their guns and

gun crews through heavy fire. Their su-

perior speed and greater maneuverability

made them harder to hit, and when they

‘were hit the armor-piercing projectiles from

the German gun-howitzers which had

punched through the 2 1/2-inch main armor

of the British mediums had much less effect

on their tougher and possibly thicker

plates. Even the much-touted German

88-mm. high-velocity antitank guns weren't

sure death to the sturdy General Grants—

one of which sustained eight hits by 88-mm.

projectiles without being penetrated by them.

In mechanical dependability and dura- |

bility our tanks were almost immeasurably

superior to those of the enemy. Ninety of

our light tanks went through an entire |

month of battle-front service with only 12

minor mechanical failures. A captured re-

port of a German workshop company shows

that after a 900-mile desert trek 44 out of

65 Mark III's were out of service because

of serious engine troubles which included

frozen pistons and broken connecting rods.

These American-built tanks were early

models of types which now have been great-

ly improved. Maj. Gen. Jacob L. Devers,

chief of our Armored Force, says that they

wouldn't stand a chance aginst the tanks

now coming off our production lines.

Our new tanks are the best in the world

because they have been made that by over

20 years of hard work, careful planning,

and patient experimenting and testing by

the tank experts of the Army Ordnance De-

partment, ably assisted by some of the out-

standing engineers of the automobile indus-

try serving on tank committees of the

Society of Automotive Engineers.

When the United States entered World

War I, the tank, first used by the British

in 1916, had been developed into a moder-

ately efficient and highly spectacular weap-

on which appealed strongly to automobile-

minded Americans. In France several bat-

talions of our newly organized Tank Corps,

using equipment borrowed from the British

and French, fought in our St. Mihiel and

Meuse-Argonne offensives and helped the

British break the Hindenburg Line. On this

side of the Atlantic, Army Ordnance officers

and civilian automotive engineers worked

almost as hard over the difficult job of de-

signing and building American tanks.

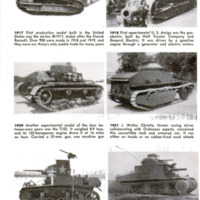

The first of their conceptions to get be-

yond the blueprint stage was the gas-elec-

tric tank built in 1918 by the Holt Tractor

Company—pioneer producers of endless-

tread tractors—and the General Electric

Company. It was powered by a 90-hp.

gasoline engine which drove a generator

that supplied current to two electric mo-

tors which drove the tracks.

The next tank produced in America was

a 50-tonner designed and built by the Army

Engineers. It was driven at a top speed

of four miles per hour by a pair of 250-hp.

steam engines and its principal weapon was

a flame thrower intended for attacks on

concrete pillboxes—an idea which the Ger-

mans have made use of in this war. An-

other of the very early American tanks

was the Skeleton—a daddy-longlegs tractor

with a small armored body slung between

its nine-feet-high and 25-feet-long tracks.

None of these experimental tanks per-

formed impressively enough to encourage

the building of a second model. As tanks

were needed badly, the Ordnance Depart-

‘ment arranged with several manufacturers

for the building of a copy of the French Re-

‘nault, which was called the Six-Ton M 1017

Tank. Over 900 were produced in 1918 and

1919. For years they were the only usable

tanks ‘in the Army, and some National

Guard companies still were equipped with

them when they were ordered into Federal

service in 1040. The Ordnance Department

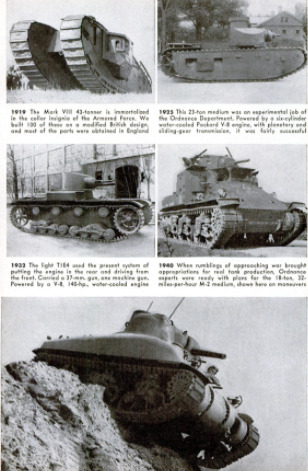

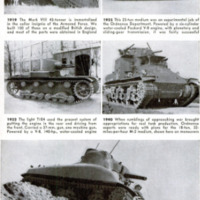

also built 100 Mark VIII 43-ton tanks of

modified British design. The first one fin-

ished was tested two days after the war

ended. This old Mark VIII is the tank

represented on the collar insignia of the

Armored Force.

Only a few of these American-built tanks

were sent overseas, and none of them were

used in action.

The 15 years following the end of World

War I were very lean ones for the Army.

Far-sceing officers were urging the neces.

sity for u degree of mechanization, but

Congress wouldn't provide the money to

buy the machines. Appropriations were so

meager that the three Ordnance officers

Who deserve chief credit for the peerless

American tanks of today had to cut a lot

corners to go on with their experimental

work. One of these officers is the Army's

present Chief of Ordnance, Maj. Gen.

Levin H. Campbell, Jr. The other two are

Gladeon M. Barnes and John K. Christmas,

both now brigadier generals and key men

in our gigantic tank-production program.

J. Walter Christie, former race driver,

Worked in close collaboration with the Ord.

nance men. The suspension and many other

superior mechanical features of our tanks

were of his invention.

Between 1920 and 1935 European armies

built tanks by the thousands. We built a

total of 31—but each of those experimental

models was an improvement over the one

which had preceded it. Engine power was

increased steadily. Tn 1926 an air-cooled

engine was used for the first time. Sliding-

gear transmissions replaced the old plane-

taries. Speeds were increased from the

five or six miles per hour of the 1918 models

to over 20 miles per hour. Steering and sus-

pension methods were improved, making

tanks more maneuverable and steadier gun

platforms. The toughness of tank armor

was increased; in 1933 the first all-welded

tank hull was produced at the Watertown

Arsenal.

From those fifteen years of hard work our

Army Ordnance tank specialists acquired

the know-how to design and build tanks

that would compare favorably with those

of any other army. When at last Congress

heeded the urgings of Gen. Douglas Mac-

Arthur (then Chief of Staff) to the extent

of appropriating funds for the building of

283 light tanks, they were ready with the

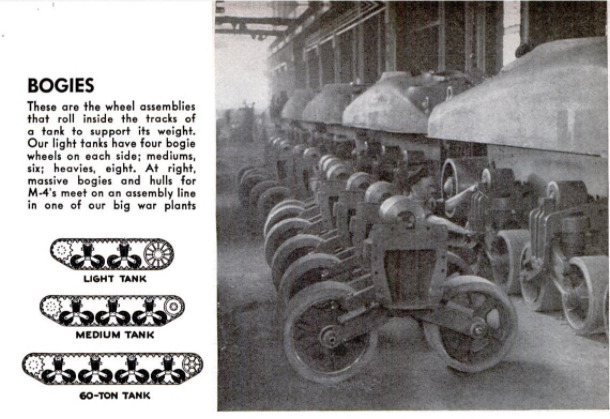

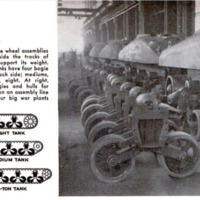

design of the M2A3. It weighed 10 1/2 toms,

and its 270-h.p. air-cooled airplane-type

engine gave it a road speed of well over

35 miles per hour. Its tracks, driven by

front sprockets and rolling over four bogie

wheels on each side which supported the

weight of the body, were made of a newly

developed long-wearing and heat-resisting

rubber composition set in steel blocks. In-

fantry tanks had double turrets; the mech-

anized cavalry

model, called a combat car, weighed a ton

less and had a single turret. Both models

were armed with .50 caliber and .30 caliber

machine guns.

Our Ordnance officers were convinced

that the M2A3 was the best light tank in

the world. Events soon proved that they

were right. In the spring of 1938 the

German Army—by then the acknowledged

leader in mechanization—invaded Austria

without having to do any fighting. Mechani-

cal failures on the road made casualties of

seven percent of its tanks. A few weeks

later our Mechanized Cavalry Brigade

marched 700 miles over hilly and blistering-

hot Southern roads in four days. Eighty-

six combat cars started the march, and 86

finished it under their own power.

The M2A3, built at the Rock Island Ar-

senal, was the first modern fighting vehicle

issued to the Army. The more heavily

armored M2Ad4, produced in quantity by

the American Car and Foundry Company,

soon superseded it as the standard tank of

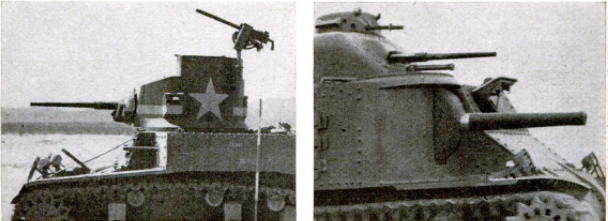

its class. The much-improved M-3 light

tank, armed with a 37-mm. gun and ma-

chine guns—now being built in large num-

bers—is its direct descendant.

In 1938 Congress authorized the building

of 18 medium tanks—enough to equip an

entire tank company! The Ordnance De-

partment was ready with plans and speci-

fications for the 18-ton, 32-miles-per-hour

Medium M-2, armed with a 37-mm. gun.

From it were developed the M2A1’s, a num-

Der of which were issued to troops in 1940.

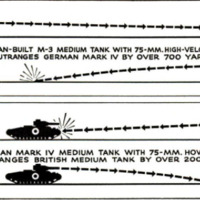

Reports from American observers at the

Battle of France emphasized the need for

more heavily armed tanks. When Congress

appropriated funds for the building of what

then seemed a large number of medium

tanks, it was decided to design a new model

with 2 75-mm. gun in a side turret in addi-

tion to the 37-mm. in the upper turret. Be-

cause of the experience gained during the

long development period, designing the

Medium M-3 took only a few months and

early in the spring of 1941 production was

started by the American Locomotive and

Baldwin Locomotive companies and the

Chrysler Corporation.

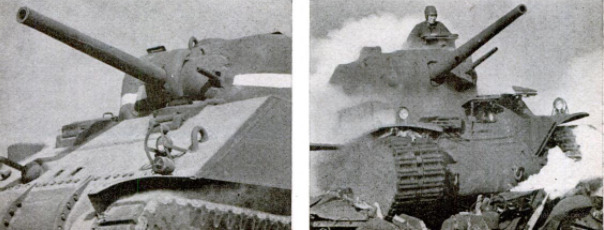

In the African battles before our in-

vasion the M-3 proved itself to be by far

the best tank on the desert. But that didn’t

satisfy our Ordnance tank experts. They

wanted to give our Armored Force an even

better medium tank, and they did it by

designing the Medium M-4.

Captured German, Italian, and Japanese

tanks have been subjected to every conceiv-

able practical and engineering test by our

Ordnance officers. These tests have con-

firmed. the strong battlefield evidence that

they aren't nearly as good as ours.

One of the reasons is that, type for type,

ours have thicker and better armor than

those of our enemies. The German light

tanks, with armor only 7/10 inch thick,

give the crews so little protection that they

no longer are used for serious combat.

The Nazi designers made the same fatal

mistake with their Mark IV medium tank.

Its original 1 1/2-inch-thick body armor has

been strengthened at especially vulnerable

spots by bolting one-inch-thick plates over

it, but these reinforcements aren’t nearly so

strong as solid plates would be.

The exceptionally high quality of Ameri-

can tank armor is the result of many years

of experimental and development work in

Government arsenals. Rolled face-hardened

plate, which keeps out the bullets of high-

powered machine guns, is used on light ve-

hicles. Rolled homogeneous plate, which

absorbs the terrific shock of large-caliber

projectiles and also affords sure protection

against machine-gun fire, is used on some

of our heavier tanks. Tank plates now are

welded together instead of being riveted.

‘The use of cast armor is increasing. It can

be cast into curved and sloping plates

which deflect many projectiles. Our new

M-4 medium tank has a cast-armor body.

Another, and very important, reason for

our tanks’ superiority is that, ton for ton,

their light and compact airplane-type radial

air-cooled engines are about twice as pow-

erful as the engines of most European-built

tanks. The ratio of engine power to vehicle

weight of World War I tanks was about

six horsepower per ton; in our modern

tanks it is about 18 horsepower per ton.

This high power-to-weight ratio makes

them faster than opposing tanks and en-

ables them to maintain speeds of from 10

to 20 miles per hour in sand or mud and on

steep slopes and over obstacles. Speed is

almost as good protection as armor—the

faster a tank moves the fewer shots hostile

tanks and antitank guns can get at it after

it comes within their effective range.

Synchro-mesh transmissions now are used

on most of our tanks, but several types of

electrical and hydraulic variable-speed

transmissions are being developed. Future

use of one of them would eliminate the

clutch. Our controlled-differential steering

-

Autore secondario

-

Arthur Grahame (Article Writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1943-03

-

pagine

-

120-127, 218, 220-221

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google Digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 14.28.49.png

Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 14.28.49.png Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 14.29.00.png

Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 14.29.00.png Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 14.29.14.png

Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 14.29.14.png Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 14.29.21.png

Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 14.29.21.png Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 14.29.30.png

Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 14.29.30.png Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 14.30.40.png

Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 14.30.40.png Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 14.30.55.png

Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 14.30.55.png Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 14.31.06.png

Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 14.31.06.png