-

Titolo

-

The irreplaceable characteristics of warships

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: Why do we keep on building battleships?

-

Subtitle: With planes challenging their supremacy, they still have work to do in war at sea

-

extracted text

-

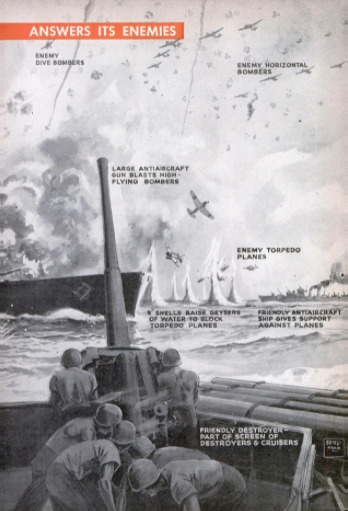

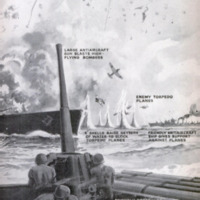

PEELING out of formation and whining down from the sky, 20 Japa-

pra dive bombers head for a U. S. battleship cruising off the Solo-

mon Islands. Aboard the surface ship, which bristles with automatic

antiaircraft cannon, gun crews are ready for them. Eight minutes of

ear-shattering fire—and the wreckage of 20 planes litters the sea.

More enemy planes are on the way, from their carriers. They try

an up-to-date strategem. Dive bombers appear first, to make the bat-

tleship elevate all its guns. A moment later, torpedo planes swoop in

from the side, barely skimming the water to launch their “fish.” The

attempted surprise fools no one. Again the battleship’s guns loose an

impenetrable screen of steel. Thrown off his aim, a Nipponese pilot

lets go his torpedo too high, and it sails harmlessly over the warship’s

stern. Now U. S. planes from a supporting carrier are getting into the

fight, and the remaining Jap aircraft flee. At terrific cost, they have

scored only a single hit on the battleship, with a 500-pound bomb. It

has landed on top of a turret, where a battleship carries some of its

heaviest armor. So slight is the damage that, less than three weeks

later, the battle wagon enters a major naval engagement and sends

to the bottom four large Japanese warships with shells hurled from its big guns.

Just made public by the Navy, these new details of the battles of Santa Cruz

and Guadalcanal, last October and November, offer an answer to the query of Al

Williams, all-out plane enthusiast, “What have battleships done in this war,

but sink?"

When Representative Carl Vinson, head of the House Naval Affairs Committee,

expressed his opinion that the aircraft carrier had replaced the battleship as the

backbone of the fleet, not a few persons agreed with him, and many went farther.

Should we keep on building huge, costly battle wagons to serve as targets for

bombs and aerial torpedoes? Alrcraft carriers were a novelty In warfare. Their

first achievements were spectacular successes, and airplanes showed that under

favorable circumstances they could sink battleships —a fact that had never been

doubted in well-informed circles. But carriers themselves are now proving as

Vulnerable as naval experts predicted before the war. And against alr power, the

superdreadnought is demonstrating its ability to strike back.

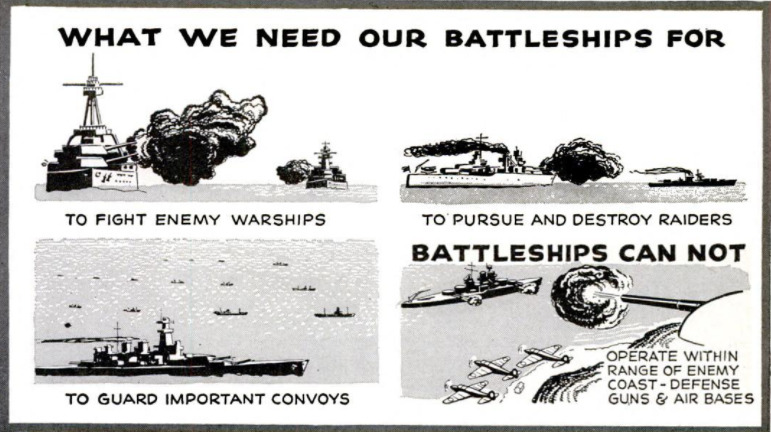

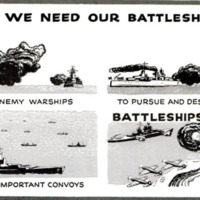

‘Why naval powers go on building battleships deserves closer looking ino. First,

just what are they for? Fighting enemy battleships is their specialty—and, in

itsele, reason enough for their necessity. Despite the heroic action of the U. S.

cruiser San Francisco, which stood up to a Japanese battleship at point-blank

range and crippled it so severely that other forces were later able to sink it, for-

tune cannot always be expected to favor brave men in outgunned ships. To keep

the enemy from our shores, to carry the war to his own, and to destroy his fleet

if it will come out and fight —or to keep it uselessly riding at anchor in port—our

battleships must be more than a match for his

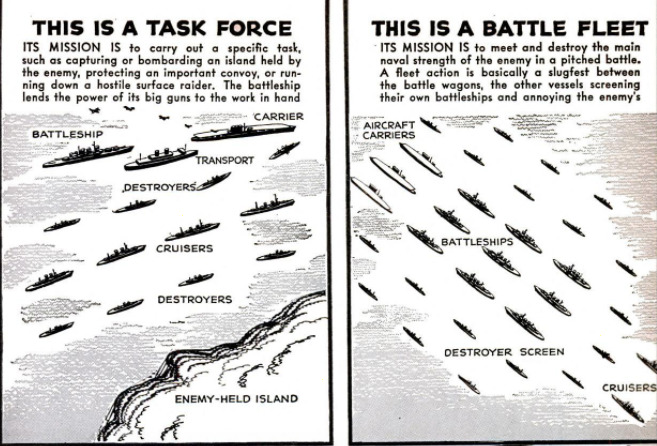

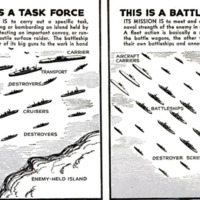

Battleships have other important tactical uses. One or more may guard a task

force, often confused by headline writers with a battle fleet. Actually the term

‘means just what it implies—a group of ships assigned to a specific mission, such as

protecting a convoy, seizing an enemy-held island, or running down & troublesome

commerce raider.

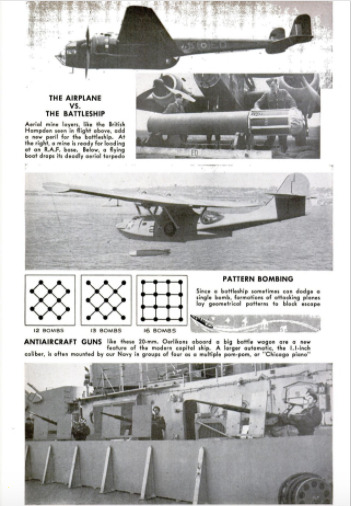

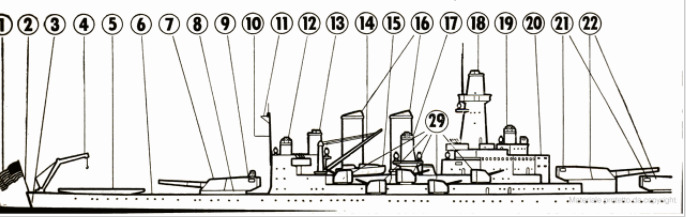

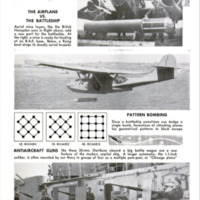

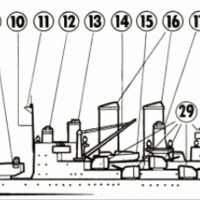

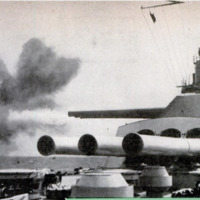

Big guns of a battleship outrange those of all other craft, and its secondary

battery of smaller guns disposes of close-range, hit-and-run torpedo attack by

destroyers. One of the outstanding changes in’ battleship design, to meet the

challenge of air attack, has been its phenomenal increase in antialrerat fire power.

Up-to-date capital ships carry sky guns ranging in size from the 20-millimeter

Oerlikon, which blasts dive bombers with 400 quarter-pound shells a minute, up

to the double-purpose five-inchers of the secondary battery, which can be elevated

to bring down high-flying horizontal bombers. An in-between size, the 11-inch

gun, lends itself especially to quadruple mounting. American design favors ar-

ranging the four barrels in a horizontal row, contrasting with the two-above-two

mounting of British pom-poms. Armor

shields for the smaller guns, and turrets for

the largest, now protect the gun crews from

fying bomb splinters.

For all its power, critics may point out,

a battleship today seldom travels alone.

Actually it is too valuable to risk an am-

bush by enemy surface ships, or a torpedo

hit from a lurking submarine. A pair of

heavy cruisers and five or six destroyers

provide about the minimum escort required

for reconnaissance and anti-submarine

screening. “Flak ships” with the sole mis-

sion of antiaircraft fire supplement a bat-

tleship's ability to defend itself, as do air-

craft carriers. Without carrier support,

capital ships cannot safely approach enemy

air bases—a lesson learned by the British

off Malaya at the cost of the new battleship

Prince of Wales and the battle cruiser Re-

pulse, sunk by only 40 Japanese planes.

Of the tactical value of aircraft carriers,

in fact, there can be no question, despite

their high rate of mortality. In the Battle

of the Pacific, at this writing, we have lost

four—the 14,700-ton Wasp, the 20,000-ton

Hornet and Yorktown, and the 33,000-ton

Lexington. The toll of Japanese carriers has

been considerably more severe. But so long

as one remains afloat, it represents a ship

of no mean striking power. Unique in

naval history was our Midway Island vic-

tory in June of 1941—the greatest naval

engagement since Jutland, fought almost

‘wholly by opposing aircraft carriers! Fully

aware of the need for ships of this class,

the Navy has a substantial total of large

ones under “rush” orders. In addition, a

number of ships begun as 10,000-ton cruis-

ers are being completed as converted air-

craft carriers. Significant in this connection

is the observation of one authority—that if

the carrier were to replace any other class

of warcraft, it would not be the battleship

but rather the large cruiser. Because of a

cruiser’s comparatively light armor, it

makes a far better target for carrier planes.

At the same time, a carrier can take over

the duties of reconnaissance formerly car-

ried out by cruisers. This last, however,

assumes favorable flying weather. In con-

trast, surface ships, including battleships,

operate in spite of fog and darkness.

Numerous night engagements have been a

feature of the second world war. In these,

the value of air power has been negligible,

with planes kept grounded because of diffi:

culty in finding and landing on their carriers.

At Pearl Harbor, Japan had demonstrated

what carrier-based planes can do to bat-

tleships under practically ideal conditions.

Taken by treacherous surprise, the motion-

less and weakly defended ships made almost

as perfect targets as painted outlines on a

practice range. Yet, of the eight battleships

there, only one—the Arizona, about to be-

come over-age—was wrecked beyond repair.

The over-age Oklahoma capsized, but may

be salvaged. None of the rest suffered mor-

tal injury, and damage to three was so

slight that they were back in service within

a few months.

Again, in the pursuit of the German bat-

tleship Bismarck, that mighty vessel showed

its stamina. Even after planes had put its

steering gear out of commission, the British

battleships King George V and Rodney had

to bombard it with about 700 shells before

a cruiser could safely close in and sink it

with torpedoes.

As to bombing attacks on battleships, few

laymen realize that it is perfectly possible

to see a bomb dropping, and change a ship's

course quickly enough to dodge it. Natural-

ly the feat requires split-second co-ordina-

tion of men and machines, but even big

vessels can do it.

To counter this annoying habit, airmen

have developed “pattern bombing.” In this

scheme, formations of planes attempt to

drop their missiles in such a design that a

ship cannot escape, no matter which way it

turns. Some imaginary patterns, reasonable

from a geometrical point of view, are repro-

duced here. Actual methods used by naval

powers ate sizicllv guarded secrets.

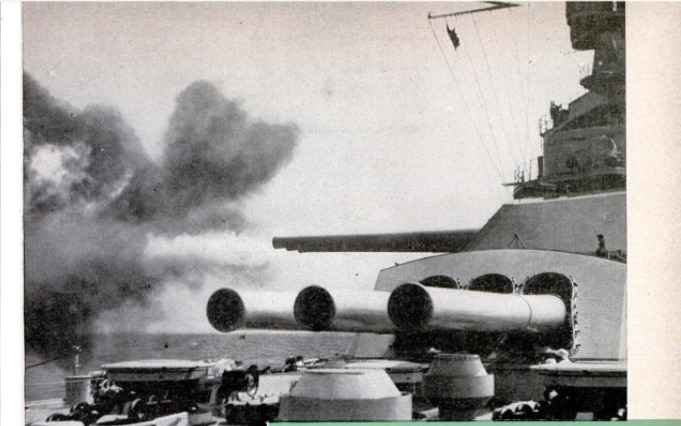

Compare bombing with shellfire, however,

and some popular illusions about air power

will evaporate. Penetrating a battleship's

tough hide with a projectile takes plenty of

velocity. Now, unlike a shell, a bomb de-

pends “solely upon gravity for its speed.

If it fell in a vacuum, a bomb would pick

up speed without limit. Since it does no such

thing, air resistance imposes a maximum

or “terminal” velocity, which a bomb can-

not exceed no matter how far it falls. No

plane has ever reached an altitude sufficient

to give a bomb this terminal velocity, but it

has been calculated, and turns out to be

about 630 miles an hour. A pilot of a mod-

ern pursuit plane could actually power-dive

fast enough to outpace the bomb and fly

under it before it hits its target! In prac-

tice, a speedy dive bomber looses a projectile

that strikes, from 2,000 feet, at something

like 300 miles an hour. Contrast these fig:

ures with the speed of a naval shell, hurled

from the muzzle of a big gun at nearly 2,000

miles an hour, and still traveling at 1,000

miles an hour when it plunges upon the deck

of an enemy ship beyond range of vision.

Of course, it is possible to imagine an aerial

bomb accelerated by a built-in rocket de-

vice. But a shell, equally adaptable to a

rocket booster, would still be the more de-

structive missile.

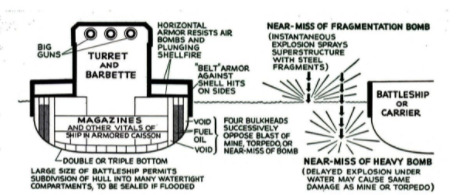

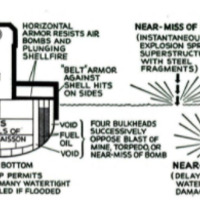

For defense against hostile gunfire, a bat-

tleship carries by far the heaviest armor of

any class of warship. The “belt” along its

sides, shielding nearly all its vital parts

from shells of flat trajectory, may measure

from 14 to 16 inches in thickness. One or

two armored decks, with a total thickness

of as much as ten inches, resist the impact

of high-angle shellfire and of air bombs.

Turrets and their deep revolving mounts,

called barbettes, receive heavy protection.

Tn modern designs, more than 40 percent of

a battleship’s weight consists of armor.

Compare the pitifully meager armor that an

aircraft carrier can carry—its flight deck,

the most important part to protect, would

be impossibly top-heavy—and it becomes

clear why battleships can slug it out while

carriers go down.

Formerly all armor plate more than four

inches thick was forged, a time-consuming

process. One American plant now turns out

armor for battleships and other warcraft

eight to 10 times as fast, by rolling it on

the world’s largest plate mill. Some of the

slabs weigh more than 50 tons apiece, and

‘measure up to 195 inches in width.

Hit a battleship below the belt—in other

words, under the side armor, which extends

only a short distance from the water line

toward the keel—and you will have struck

its most vulnerable spot. Because of the

hammerlike blow with which water trans-

mits an explosion, a near miss by an air

bomb fused for delay action can inflict seri-

ous hull damage. Mines and torpedoes, both

now carried by airplanes, offer added dan-

ger. Even a single torpedo hit means an

eventual trip for repairs. Though still afloat,

a badly damaged ship may be slowed enough

to become the prey of submarines, which

could not catch up with it otherwise.

Many ingenious schemes have been ap-

plied to minimize underwater damage. One

plan is to make the outermost compartment

of the battleship a false hull or “blister,”

leaving it empty. In this idea, the blister

explodes the torpedo. Compressible air,

within, absorbs some of the force of the ex-

plosion and evenly distributes the rest. The

inertia of liquid in inner compartments helps

their bulkheads to take up more of the

shock. Since a battleship’s hull is large

enough to be highly subdivided into water-

tight compartments fore and aft, it can take

a good many torpedo hits and remain in

action.

Concerning the increased peril brought

about by aerial torpedoes, it has become

traditional that each innovation in naval

weapons has promptly been countered by a

means of defense. Magnetic mines, for ex-

ample, lost their terror when ships were

equipped with degaussing cables.

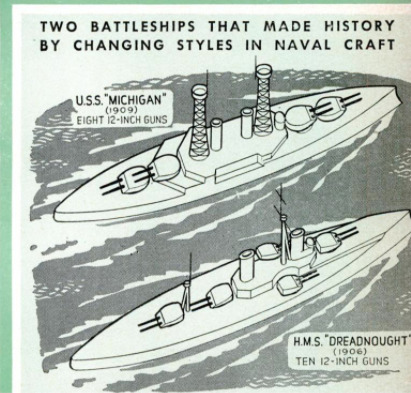

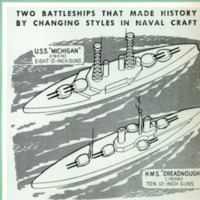

In the evolution of battleships, both Brit.

ain and America have been pioneers. Two

vessels in particular have made naval his-

tory. H.M.S. Dreadnought, the prototype of

its class, introduced in 1906 a main battery

consisting entirely of big guns. Three years

later, the U.S.S. Michigan set the style for

present-day arrangement of all main turrets

along the center of the ship, permitting the

full force of a broadside to be delivered

either to port or starboard. Practically all

modern men-of-war follow these basic prin-

ciples, even though today’s capital ships

dwarf the earlier ones.

Other American innovations include the

first steam warship; the first screw-pro-

pelled man-of-war; the first ship-based

take-off and landing of a plane; and the

supposedly modern art of zigzagging. Fly-

ing in the face of naval tradition before

that time, the maneuver was introduced to

dodge shellfire as early as the Spanish War.

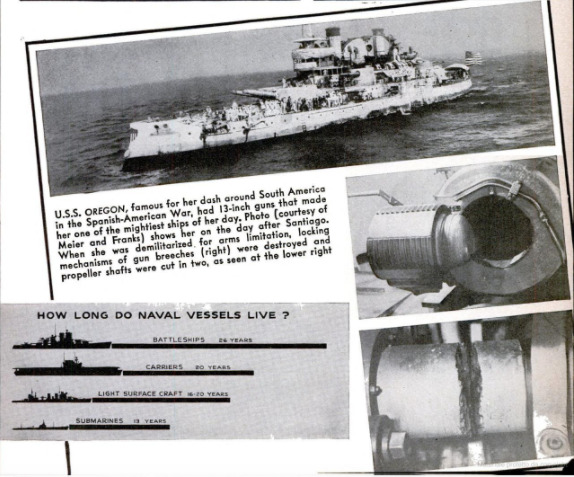

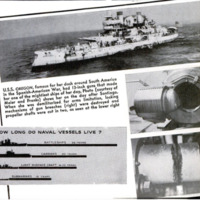

One of the most powerful warcraft of her

time was the 10,000-ton battleship Oregon,

famed for her record-breaking dash around

Cape Horn in time to help destroy the Span-

ish fleet at the Battle of Santiago in 1898.

The four 13-inch guns of her main battery

‘were the most formidable in existence. Now,

after years of honorable retirement, the Ore-

gon is going to serve her country again. The

historic vessel will be scrapped, and reborn

in mighty fighting ships called for by our

huge construction program.

Since naval designers attain the best com-

promise between guns, armor, and speed in

warships of great dimensions, battleships

are reaching unheard-of size today. By

now, although the Navy does not announce

commissionings in wartime, four sister ships

of the new, 35,000-ton North Carolina and

Washington may reasonably be assumed to

be in service. And the first two of five

projected 45,000-tonners, the Jowa and New

Jersey, have been launched.

This 45,000-ton figure, at least, was the

size originally announced when they were

laid down in 1940. More recently, the Navy

has made it known that their design has

been changed to incorporate results of

lessons learned in the current war. Exact

figures for their displacement are now a

wartime secret. However, the New Jersey

was said by the Navy to have a slightly

greater tonnage displacement than her sis-

ter ship, the Iowa, when she slid down the

ways into the Delaware River at the Phila-

delphia Navy Yard. She will be the heaviest

battleship ever constructed.

Some doubt exists about plans for a fu-

ture 58,000-ton Montana class proposed

some time ago. The Navy has announced

no decision not to build them, but their con-

struction may be postponed in-

definitely, in favor of more urgent

shipbuilding. Critics point out that

the ships quite possibly might not be

completed in time to see service in

this war. Every increase in size im-

poses added difficulties in negotiat-

ing shallow channels, in finding suit-

able harbors, and in being dry-docked

for overhaul and repair. Too, there

may be a point at which a battleship

becomes so huge and expensive that

its loss from any cause would be

a national calamity. Perhaps two

smaller battleships, built at some-

thing like the same total cost, would

be more useful than the big one.

‘Whatever we do build in battleships,

however, seems beyond the power of

aviation extremists to criticize suc-

cessfully.

-

Autore secondario

-

Alden P. Armagnac (Article Writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1943-04

-

pagine

-

62-72

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google Digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 15.18.10.png

Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 15.18.10.png Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 15.18.01.png

Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 15.18.01.png Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 15.17.53.png

Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 15.17.53.png Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 15.17.44.png

Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 15.17.44.png Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 15.17.37.png

Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 15.17.37.png Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 15.16.39.png

Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 15.16.39.png Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 15.16.49.png

Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 15.16.49.png Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 15.16.57.png

Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 15.16.57.png Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 15.17.03.png

Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 15.17.03.png Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 15.17.14.png

Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 15.17.14.png Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 15.17.24.png

Schermata 2022-02-22 alle 15.17.24.png