-

Titolo

-

U.S. war technologies overview

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: For The Defense of - America Attacked

-

Subtitle: What Brave New Weapons Gird Our Fighting Men? Carl Dreher Reveals How Embattled Industry Met The Challenge of Axis Threats to Our Freedom

-

extracted text

-

A “NEW” weapon is never altogether new.

Generally speaking, it is just an improved

machine for killing enemy personnel and de-

stroying enemy equipment. There is always

the possibility of hitting on something spec-

tacular and unprecedented, but Superman is a

character in a comic strip and there are no

supermen in the actual world of designing and

operating fighting machines. For the most

part military progress is a military engineer-

ing job in which a small or moderate improve-

ment here and another one there add up to a

decisive advantage in combat.

Our naval weapons are a case in point. The

things they do were almost all done in the first

world war and before. But the new ships do

them faster, more accurately, and with

more stunning force. Their speed is greater,

because their engines are more powerful,

and a further increase will soon be effected

when propellers are designed with controll-

able pitch so that the interaction of the

screw and the water pushes the hull ahead

with maximum efficiency. Their fire is more

accurate; the integrators and control de-

vices split finer hairs than they used to and

compensate for everything that is compens-

able. When the shell strikes it works great-

er havoc, because the rifle is bigger and the

propellant powder timed for just the right

shove in the barrel and perhaps the explo-

sive in the shell is even more violent. And,

not least important, the new ships are bet-

ter protected against the blows which they

in turn must sustain from the enemy's guns.

The new North Carolina is the last word

in battleships—until the next dreadnought

is commissioned. In guns, speed, and armor |

she has no present equal in our Navy or |

any other. Her nine 16-inch guns, arranged |

in two turrets forward and one aft, are de-

signed to hurl a broadside of some ten tons

of steel and TNT over 20 miles of ocean. |

She carries 20 five-inch rifles as secondary

armament. These are double-purpose, tur-

ret-mounted guns equally useful against sea

targets and aircraft. For close work against

dive bombers or torpedo planes, the North |

Carolina carries multiple-barreled 1.1 inch

pom-pom guns firing one-pound explosive |

shells, It is a formidable aggregation of

guns, something to be pondered over by the

naval strategists of the Axis powers—and |

they will have even more to think about

when the five battleships of the Montana

class take to the water with twelve 16-inch |

or 18-inch guns and secondary armament to

match,

In war ability to take it is as important

as ability to dish it out. Torpedoes, shells, |

and aerial bombs may shake the North |

Carolina, kill many of her crew, perhaps

disable and sink her, but it will require a

greater tonnage of explosives, more accu-

rately placed, to put her out of action than

any battleship of earlier design. Antitorpedo

buiges, watertight compartments, side ar-

mor probably 16 inches thick, and 10-inch

deck armor are among her known protec-

tive features. Nor does she lack auxiliary

protection for personnel in the form of top-

side armor as heavy as she can safely

carry. When she must, she can run as well

as chase, Her high-pressure turbines and

quadruple screws will probably enable her

to exceed her rated speed of 27 knots. It is

ironical to talk of safety in connection with

a combat ship, but the North Carolina is

about as safe a battleship as can be de-

signed with existing knowledge and ma-

terials.

The most highly industrialized countries,

strain as they may, cannot produce battle-

ships by the dozen. But the smaller com-

bat craft, which can be turned out on some-

thing more like a mass-production basis,

are just as important in the aggregate,

These types, moreover, are being improved

as rapidly as the ships of the line. New

destroyers are heavier, better-gunned, and

less vulnerable. The Kearny incident shows

that a modern destroyer is no longer the

type of vessel which only has to be hit once

and it is headed for the bottom. The mod-

ern destroyer is more like a light crulser

in this respect, and there will be even less

difference in the future. The typical Ameri

can destroyer of current design displaces

1,500 tons and up, with the heavy destroy-

ers which act as squadron leaders running

as high as 1,850 tons. On the offensive, such

ships, mounting eight to 16 torpedo tubes,

six 5-inch guns, and a heavy complement of

smaller high-angle guns for action against

airplanes, are a match not only for oppo-

nents of their own size but often for those

considerably larger. Their principal ad-

vantage is high speed and extreme maneu-

verability, consequent on thelr tremendous

power plants, which are about ten times

bigger, in engine horsepower per ton of hull,

than those of battleships. The destroyer,

of course, is the weapon par excellence

against the submarine, and it is equally

indispensable for screening, scouting, con-

voying, and auxiliary operations.

The destroyer is fast and maneuverable,

but the ultimate in speed and marine acrobat-

ics is reached in the motor torpedo boats,

which tear through the water, or rather on

it, at speeds around 60 miles an hour, and

turn corners like a boy on roller skates. Car-

rying three supercharged 1,350-horsepower

engines and a complement of eight men, a

boat of this type is by no means inexpensive

either in a monetary or a military sense.

Still, it can be risked and if necessary lost

with less over-all damage than a larger

fleet unit, and on the other hand it consti-

tutes an’ entirely disproportionate hazard

for any battleship at which it aims its four

torpedo tubes. If the battleship blows the

‘mosquito boats out of the water the battle-

ship has accomplished substantially noth-

ing, while if the torpedo finds its mark there

is likely to be one less battleship and the

mosquito boat has accomplished substan-

tially something. The essence of war is to

do the greatest possible damage with the

least possible expenditure of men and equip-

ment, and the mosquito boat is one of the

solutions of this problem as far as naval

warfare is concerned,

A navy worth its taxes is not a random

conglomeration of ships, but a technological

unity like any other producing organiza-

tion. It happens to produce destruction in-

stead of goods, but that in no wise lessens

its need for first-rate codrdination in opera-

tion, maintenance, and all the other highly

technical functions which Keep the wheels

turning. The range of these activities is so

great that even a cursory description is

impossible. But one phase of the Navy's

special operations warrants description be-

cause of its certain future importance, and

the more 50 in that it entails joint maneuv-

ers with the Army—always a difficult situa-

tion for both services. The job is that of

transporting troops over water.

In the last war, Army units carried over-

seas were regarded more or less as human

freight: so much space had to be provided

to accommodate so many men, and the ships

assigned to this duty were simply freighters

or passenger vessels rebuilt to carry as

many troops as possible. Since this was

before the days of air power and there was

no problem of landing troops on a hostile

shore, this system functioned successfully

enough at the time. But the present war

will call for establishing beach heads and

landing large bodies of troops under fire.

Consequently it has been necessary to adapt

existing oceangoing bottoms to carry sea-

going combat units with all their equip-

ment, ready for action, and in addition to

devise means of getting the men and ma-

tériel off the transports to the beach. The

latter job is handled by armed, self-pro-

pelled, ‘shallow-draft landing boats between

36 and 45 feet in length. Powered with a

250-horsepower motor and protected by a

machine-gun turret in the bow, such a boat

can bring to shore from 40 to 190 fully

armed men, or a smaller number of men

and a light tank. The speed is 25 knots.

When the boat runs up on the beach, the

hinged end is lowered to provide a run-

way for the tank or other vehicle.

The failures and fiascoes of American

plane production in World War I are an un-

pleasant memory. In the present war Amer-

ican plane design promises to write one of

the most brilliant chapters in the whole

history of air technology. Our only prob-

lem is reaching peak production in time.

The models themselves can hardly be

praised too highly—and this is not the

opinion of the men who built them, but of

foreign pilots who have been fighting in

them. The planes are good all along the

line, from the smallest pursuit craft to the

heaviest bomber. The light bomber or at-

tack plane—Douglas A-20-A—used by the

British as a night fighter under the name

“Havoc,” is only one example. In the United

States it is used largely as a reconnaissance

bomber and in close support of ground

troops. Flying at very low altitudes, the

A-20-A blazes away at a supply column

with its forward machine guns and drops

parachute-retarded fragmentation bombs

behind. The A-24 dive bomber metes out

similar punishment to point targets.

The Army's medium bombers fly as fast

as some of the best 1941 European fighters.

American heavy bombers climb to 37,000

feet and at the higher altitudes are capable

of running away from most fighters within

their bombing range of 3,000 miles. As a

sample of the heavier bombers to come, the

80-ton Douglas B-19, with a wing spread of

210 feet, has four engines totaling 8,000

horsepower which will fly it 6,000 miles at

a speed of 200 miles per hour. In the inter-

ceptor and pursuit line we have some of

the fastest models in the world. Something

may also be said of the less publicized train-

ing planes. In the long run, trainers may

De only less important in the winning of the

war than fighters and bombers.

The U.S. Navy, which has been building

some of its own planes since 1918, is con-

ceded to have the best naval air force in the

world. Its patrol bombers are vital for

coast defense, locating commerce raiders,

and the like, and in a war of attrition will

assume even greater importance. It will be

remembered that it was a Catalina (Con-

solidated PBY-5) flying boat which inter-

cepted the Bismarck on the voyage which

ended in her destruction. The Navy pio-

neered the technique of dive bombing and

in this field it has the Douglas SBD Daunt-

less, which corresponds to the Army's A-24,

and the Curtiss Helldiver, SB2C-1, which is

said to be the deadliest of the lot. Another

U.S. Navy development is the torpedo

bomber, and its Douglas Devastator (TBD)

is much better than the British Swordfish

which knocked out a good part of the Ital-

ian Navy at Taranto.

Naval antiaircraft equipment has already

been mentioned in connection with the

USS. North Carolina. During 1942 the

Army will have available in quantities its

4.7 inch AA gun, which should be effective

in the substratosphere region where heavy

bombers now travel. For medium altitudes

the Army, on the basis of European per-

formance and its own tests, has adopted

the 40-mm. funnel-mouthed Bofors auto-

matic cannon, which fires in bursts of four

or five rounds with a muzzle velocity of

2,850 feet per second and has a virtually

straight trajectory up to over 9,000 feet.

The weight of the projectile is 2.2 pounds,

and it will tear apart any airplane wing it

hits, or knock the plane out of control if it

explodes nearby. It is not a new weapon,

nor of American origin, but part of the

knack of winning wars con-

sists in holding on to old de-

signs until something mate-

rally better offers, and in

borrowing whatever is good,

wherever it is found.

The great new development

of the current war is, of

course, mechanized warfare,

of which the Nazis have been

the chief protagonists to date.

In this connection a recent

writer in the austere “Com-

mand and General Staff School Military

Review” quotes dryly, “There ain't no hoit

What can't be broke.” And that sums up

the situation accurately and briefly. Masses

of tanks and armored divisions are power-

ful weapons, but mechanism can cope with

mechanism—a principle which the hitherto

invincible German armies have already en-

countered in Russia, and will no doubt run

up against on other hattlefronts.

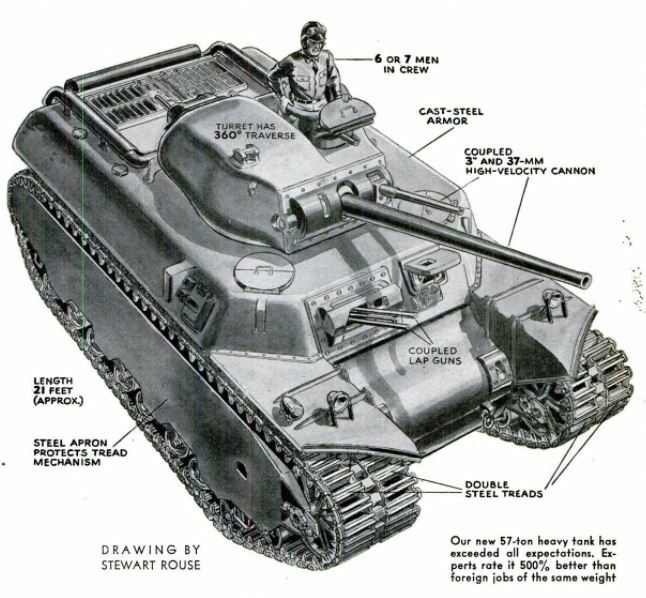

‘The trend in tanks has been toward heav-

for types, with armor good against at least

40-mm. projectiles. American. production

has been largely confined to the light tank

of about 15 tons, which has given a good

‘account of itself in Libya and, by reason of

high speed, good maneuverability, and me-

chanical excellence, can under some condi-

tions cope with equal numbers of German

medium tanks. It is normally equipped

With & 37-mm. gun and several machine

guns. During 1042 our 28-ton medium tank

will be brought into heavy production and

is expected to come up to the mechanical

standard of the light model. Armament

consists of a 75-mm. cannon, a 37-mm. can-

non, and machine guns in the turret and

cupola. The first heavy American tank

passed the Army tests at the Baldwin Loco-

motive Works early in December, 1041. It

welighs 57 tons, mounts one 3-inch and one

7-mm. cannon and a battery of machine

guns fore and aft, and has exceptionally

high speed for its weight.

The most obvious defense against the

tank is a better tank, or, if tanks are un-

available, an anti-tank gun heavy enough

to plerce the attacking tank's armor. Such

a gun must be self-propelled and lightly

armored to afford some protection to ita

operators. Essentially, therefore, it 1s a

light, single-gun tank In which armor has

been sacrificed for the sake of speed and

‘maneuverability. One tank specialist esti-

‘mates that a given number of AT guns can

cope with three to four times as many

tanks. The United States has developed |

self-propelled guns in calibers from 37-mm. |

to 155-mm., the 37-mm. and 75-mm. sizes

being designed especially for AT operations, |

or, as they have lately been designated, tank

destroyers. |

A recent development in

tank construction is the use

of cast or welded steel bodies.

The 57-ton type mentioned

above is of this type. Earlier

tanks, such as the American

product used by the British

in the Libyan campaign, were

riveted. When anything has

to withstand great pressures,

it is usually best to make it

one piece. In the case of the

tank, rivets have the additional disadvan-

tage that when struck by an armor-piercing

shell they may be driven into the interior

as secondary projectiles.

In an age of total war there is no practi-

cal distinction between military weapons

and the weapons of civilian production. An

improved method of geophysical explora-

tion for petroleum might help to win a war

as much as an improved machine gun. A

medical development, such as an improve-

ment in psychaitric tests used in selection

of student flyers, might be a military factor

of outstanding importance. Organization

itself is a weapon: a body like the National

Inventors Council, which sifts defense in-

ventions and separates a few kernels of

wheat from a vast volume of chaff, is not

to be underestimated. In this field of scien-

tific organization, incidentally, we are likely

to gain a long-term advantage, because

while the Nazis are superlatively organized

for the application of science to the ends of

destruction, their methods of internal sup-

pression and persecution are likely in the

end to dry up the sources of invention. Ger-

many nearly won the last war with Fritz

Haber's fixation of nitrogen from the air;

there will be no Haber for them this time,

for he happened to be a Jew.

The battleships, tanks, planes, guns, ve-

hicles with which our men will fight are

good, and the men are good. What then are

the prospects? All that can be said is that

the short-term outlook Is poor, the long-

term outlook favorable. We were not ready

when we entered the war and shall not be

thoroughly equipped for some time. But

we have the men and the machines and the

production capacity to see it through. And,

not of least importance, we are learning

from our mistakes. To work and to learn,

to be energetic and educable, is in the last

analysis the primary national weapon for

which there is no substitute in war.

-

Autore secondario

-

Carl Dreher (Article Writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1942-02

-

pagine

-

72A-74

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google Digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Roberto Meneghetti

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)