-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

U.S. bombers strategy

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: How America Has Developed Her Sky Destroyers

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

THERE IS NOTHING STATIC about

military aviation in any of its phases.

It is always doing things in a new way, and

almost before one’s eyes the new ways be-

come old. But the pace of change is swift-

est in that branch least known to the pub-

lic: air support. It is so new and develop-

ing so fast that as yet it has no printed

literature. The Army's thoughts about it

are set down in 20 mimeographed pages,

mostly general theory. The rest is in the

heads of the men who are doing it.

Air support covers all forms of air action

undertaken in conjunction with ground op-

erations. The word “support” has a some-

what passive, defensive sound. It is mis-

leading. In actual practice the only way

in which the combat fiyer can help the

ground forces to which he is attached is by

attacking the ememy. When the ground

troops are stuck and on the defensive, he

attacks. When they are advancing, he at-

tacks again. And when he is not sure

whether they are coming or going, he still

attacks and keeps on attacking as long as

he can see anything on which to train his

machine guns or drop his bombs.

The support pilot's job contains a mini-

mum of routine and conventional precedent.

The long-distance bomber pilot's missions

are dangerous and complicated enough, but

at least he has a definite objective. His ob-

jective folder, with its maps and data, is

supposed to contain all he needs to know

to get his bombardier above an identifiable

target in a fixed location so-and-so many

miles away. The interceptor pilot's think-

ing has to be as fast as the flight of his

machine, but he too knows what is expected

of him—to bring down bombers which have

been reported at a given altitude on a given

axis of approach. But the support pilot

usually lacks even these few certainties of

probabilities. As he takes off, he may not

know where his target is or what it looks

like, or whether there is going to be a tar-

get at all. He may not know how far he

will fly or how long he will be gone from

his home field. He may have specific in-

structions and be unable to carry them out,

and yet his mission may be highly success-

ful. In all these things his situation is quite

different from that of other combat flyers.

In only one respect are they all alike: none

knows whether he will return.

Air support as we now know it—and it

will not be the same a year hence—is a

natural development from an earlier state

of tactical procedure. Let us take a specific

situation and see how it would have been

handled in the past and how it is handled

now. In the diagram below, C is a column,

motorized or otherwise, advancing in the

direction of a ridge or other natural ob-

struction. Here opposition is encountered

from a screened point X on the other side.

The forces at X are unknown. To attempt

a frontal assault would be very much like

passing near the brow of a hill in an auto-

mobile. There may be nothing in the way,

or there may be an oncoming truck. It is

best not to make the experiment.

Under earlier conditions, the commander

at C might have telephoned to the nearest

airdrome, A. An observation plane would

have gone up. When the observer returned

C would have got more or less complete in-

formation on the strength and disposition

of the enemy forces to guide him in his next

move. He might then have asked for an

attack plane to dislodge the obstructing

forces. But whatever action was taken,

time had been lost, and while it was being

lost X might have been busy to good ad-

vantage.

The modern tempo is faster. As soon as

serious opposition is encountered, C reports

to H, an air-support headquarters in touch

with A, and all other airdromes in the

neighborhood, and with all planes in flight.

Instead of an observation plane, a light,

fast bomber is dispatched. The crew of this

machine can make observations, perhaps

not as well as from a slow observation

plane; on the other hand they are not as

vulnerable to counterattack. But the great

advantage of the method is that the recon-

naissance bomber, as it is called, can not

only get information, but, acting on what

the Army calls air judgment, do something

about it then and there. He may, for ex-

ample, deposit a few fragmentation bombs

on X, and, observing the effects, inform H

by radio that the column can now proceed

over the ridge without too much hazard.

Of course this is a schematic and over-

simplified picture. X may have his own

airdrome, A, and C may be the one that is

attacked and dispersed. It is a question of

Who gets there first with the most bombs.

But the method is clear. It is an illustra-

tion of close support—intervention by air

on the battlefield. This is one major division

of air-support responsibility. The other is

direct support, which is defined as attack

on targets behind the battlefield, to isolate

the battlefield as far as the enemy is con-

cerned, to prevent him from bringing up

reinforcements by attacking his troop con-

centrations, interrupting his supply lines,

destroying his airdromes and planes based

thereon, etc. It is a type of bombing inter-

mediate between close support and long-

range strategic bombing, but nearer the

former.

‘The fluidity of the support bomber’s situ-

ation arises from the fact that he operates

over a battle front, and that front is some-

thing which extends over a wide area and

changes by the hour and sometimes by the

minute. His targets are where he finds them

—opportunity targets. He is on his own.

Yet free as he is to exercise his independ-

ent judgment and in fact compelled to exer-

cise it every minute, he is still a member of

a general plan and organization. He is

constantly in touch with headquarters by

radio. There is no sharp dividing line be-

tween the two ends of the radio circuit.

Teamwork on the ground means teamwork

in the air, and vice versa. At headquarters

there is an air-support officer and ground

officers—often from both the infantry and

the artillery. The location of the control

is at or near the ground command post.

Here everything can be coordinated, here

the staff work is done and the major de-

cisions made. The officer in charge is the

quarterback: he calls the plays. The play-

ers plunge and twist in their own way,

taking advantage of the openings on the

spur of the moment. It is this combination

of integrated effort and individual initiative

that wins battles.

The directing heads are on the ground

but many of the decisions are made in the

air. When, for example, a reconnaissance

pilot blows obstructing forces out of the

way, he has in effect made a decision. The

mechanized forces on the ground can go

straight ahead. When, owing to strong air

opposition, antiaircraft fire, or adverse

weather conditions, he cannot solve the

problem in such summary fashion, he may

still be able to facilitate the advance by ad-

vising a movement around the hostile units,

or some other maneuver suggested by his

observations. In any case the decisions on

the ground are made largely on the basis

of what he sees and does from his moving

vantage point above the battlefield.

The diversity of the jobs he is called on

to do is almost unlimited. Clearing away

impediments to the advance of motorized

forces is only one of them. One of his prin-

cipal missions is to take out antitank guns

to facilitate the advance of our own tank

attacks. One of the most important lessons

learned from study of the German air-

ground combat-team action is the technique

used by the Stukas in destroying antitank

guns to prepare the way for tank advances.

After a break-through the support bomber

protects the flanks of the penetrating forces.

He is active in covering parachute troops

and air infantry during transit and landing,

and in preventing the enemy from bringing

up an overwhelming force to wipe out such

detachments after they have seized a stra-

tegic position. The tendency is to extend

the operational field of support aviation

both in a geographical and a functional

sense—to assign new missions to the sup-

port groups and let them range farther

afield in performing new and old missions.

Aside from the training, experience, and

enterprise of personnel, the factors which

make for success in support aviation are

offensive weapons, including airpla es and

their armament; communications and con-

trol, and strategic location of airdromes.

The last is not the least important. In gen-

eral it is desirable to base support aircraft

close to the fighting front, so that planes

can be in action in the least possible time

after taking off. This makes the rapid con-

struction of forward or advanced airdromes

a prime necessity. New, specialized organi-

zations are being developed for this purpose

by the Corps of Engineers. Two battalions

of specially trained engineers, comprising

a force of 1,000 to 1,200 men, can in about

two weeks clear and grade an emergency

field large enough to accommodate all types

of military planes. Many such fields are re-

quired, because, quickly as they are built,

they are even more quickly damaged. For-

ward airports, and the planes based on

them, are of course a favorite target for

enemy bombers, and around each principal

field there must be auxiliary fields for dis-

persal of aircraft, so that when an attack

comes there will not be too many eggs in

any one basket.

An advance airport comprises a great

deal more than a flat, hard surface. Unless

it is to be used only as an emergency land-

ing spot, it requires gasoline stores, a power

supply, some repair facilities, and shelter

for personnel. The Army has repair trucks

for aircraft, carrying all necessary hand

tools and even light machine tools, and re-

cently flying repair shops have been added.

These are transport planes equipped with

tools for emergency repairs to enable a

damaged ship to be flown back to a repair

depot. Another auxiliary service that can-

not be dispensed with at the front is avia-

tion weather forecasting. When urgent

need arises, military fiers are willing to go

up in any kind of weather that by some

stretch of the imagination can be termed

fiyable, but the least the ground forces can

do is to keep them informed on what they

are going to encounter. Accordingly, where

tactical units go the mobile weather units

must go, to make local observations and

maintain contact with the weather stations

in the rear by teletype and radio. Ease of

communication is likewise vital to support

aviation: without an efficient communica-

tion service there can be mo effective co-

ordination between units. Visual signaling

is used to some extent for communication

with airplanes flying in close support. But

the principal contact between air and

ground is of course by radio, both voice and

telegraph. Since, flying near and over enemy

positions, the operators must expect their

messages to be monitored by hostile sta-

tions, simple secrecy codes are devised to

designate targets, time of attack, number

of planes, and the like; and these codes are

re-keyed as often as necessary. (Continued)

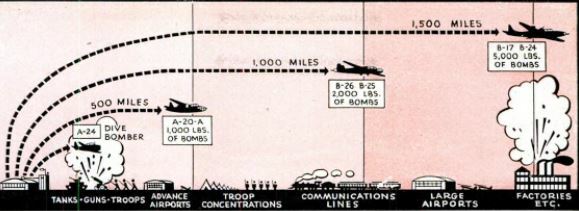

The planes most frequently used in sup-

port of ground forces are the A-24 dive

bomber and the A-20-A, a fast, short-range

two-engined bomber. (The A-20-A’s were

one of the features of the recent maneuvers

in the damage they inflicted on the Red and

Blue armies.) The more powerful medium

bombers of the B-25 and B-26 types also are

used in support, but for the most part it is

a light bombardment job and smaller bomb-

ers fill the bill. For close support the dive

bomber is preferred. European experience

indicates that its reign as en instrument of

terror is already over. The French may

have been stunned by the German dive

bombers; the Russians were not, and shot

down great numbers in the fall of 1941.

But, regarded as just another weapon, in-

dicated in some situations and contra-indi-

cated in others, it has its place. Its accur-

acy and maneuverability fit it for use

against precision targets and what the

Army poetically calls “fleeting targets of

opportunity.” Most free-lance bombing in

close support is of this character. The tar-

gets may be troop concentrations or move-

ments, minor field fortifications such as pill-

boxes, motorized columns, artillery in posi-

tion or in motion, etc. The effectiveness of

the attack depends on speed and surprise.

The pilot takes off, sees what he is after,

and dives at it. The usual height at the be-

ginning of the dive is around 8,000 feet. A.

descent of about 4,000 feet is usually re-

quired for the 70-degree angle favored in

this kind of operation. At an altitude be-

tween 3,000 and 4,000 feet the bombs are

released. The plane levels off

at 1,500 feet and zooms away.

In direct support horizontal

bombing is preferred. The

A-20-A affords greater bomb-

loading than diving aircraft

and has the additional advan-

tage of high speed in horizon-

tal flight. The prey of the

A-20-A is lines of communica-

tion, airdromes and aircraft

on the ground, bomb dumps,

troop concentrations, com-

mand posts, and the like. Most

of the work is done at low al-

titudes. The attack bomber is

necessarily a_grass-cutter at

times; he is not reckless, but

he works at the most effective

altitude, whatever that may

be. At very low levels he relies

on great speed relative to the

target and its defenders for

protection. By flying close to

the ground and taking advan-

tage of the cover of trees and

hills he can often surprise his

objective, and be off before ground crews

can aim their guns.

The conventional weapons of the attack

bomber are the machine gun and the bomb,

and the bomb is the more important. The

big bombs used in long-range strategic

bombing are mot suited for support avia-

tion. In this field multiple assaults with

comparatively light bombs are most effec-

tive. As far as possible, loading is limited

to a very few types. Against fortifications

demolition bombs weighing between 50 and

250 pounds are standard. Demolition bombs

operate by concussive pressure or blast,

consequently almost half the weight con-

sists of TNT. Against personnel, fragmen-

tation bombs are used. These usually come

in 30 and 100-pound sizes, and they differ

from demolition bombs in that most of the

weight is in the metal case. An ordinary

fragmentation bomb contains less than five

pounds of TNT. Such bombs will damage

light material targets, such as airplanes on

the ground, but their primary purpose is to

kill. Machine guns of .30 and .50 caliber

are similarly used against ground troops,

and also afford protection against hostile

aviation.

A new factor in close-support operations

is the growing conviction that the light

bomb is not the weapon to destroy tanks.

The problem of attacking tanks from the

air has not been solved—in fact, until some

better method is devised, there is the feel-

ing that tanks must be hit by air-borne can-

non, such as the 37-mm. carried by the P-39,

a pursuit ship. The success of these guns

in antitank operations from the air during

the recent Army maneuvers suggests the

possibility of their eventual use on the light

‘bombers.

These are the weapons. Their tactical use

is something that cannot be blueprinted. All

military operations, as planned in advance,

are in a sense a preparation for the unex-

pected. Yet there are some fairly well-de-

fined rules for the most effective use of sup-

port aviation. These relate mainly to the

optimum number of planes for a given op-

eration. Against precision targets and in

close support the single airplane is most

adaptable and gives the best results. It is

likewise effective against linear targets, such

as marching or motorized columns, but usu-

ally such objectives are important enough

to warrant the use of small formations—

loose three or four-plane elements. Such

columns are very inviting targets for sup-

port bombers. The attacking units approach

obliquely, turn, and fly over the objective

only during actual delivery of offensive fire.

The conventional method is for the leading

plane to line up the target with the gun

sight, nose down and deliver forward ma-

chine-gun fire, level off, and release bomb

loading. The following planes repeat this

procedure on other portions of the column.

Usually a single pass is sufficient to obtain

effective hits. When defensive fire is heavy

it is inadvisable to make more than one

pass; the defenders are apt to be more ac-

curate in thelr aim the second time around.

Larger formations, up to squadron size

(12 to 15 planes) may be used against area

targets. A squadron is about as much as

one commander can handle in the air, and

the target has to be worth while to warrant

80 much risk and expenditure of material.

In these cases a bombing pattern is worked

out in advance, with each plane in the squad-

ron assigned to a specific portion of the area.

The altitude is likely to be comparatively

high and the bombsight is necessary for ac-

curate aim.

If, in accordance with present plans, we

are to have an air force of 500,000 men, the

support groups will have to be a great deal

larger than they are now. The present air

support is good —what there is of it. Train-

ing additional personnel will be a consider-

able job in itself. The problem is one of joint

training. Air-support fliers must have at

least a fair understanding of ground-force

operations and dispositions, besides the tech-

nique of air attack, communication, map

and photograph reading, and all the other

subjects with which they must be familiar.

The ground forces, for their part, must learn

the potentialities and limitations of combat

aviation, ground reconnaissance with a view

to selecting targets for aviation, signaling to

aircrat, and so on. Above all, once the ele-

mentary stages have been passed, there

must be joint training in maneuvers. The

soldier, like other men, learns mainly by

practicing what he has been taught. The

frequent use of ground officers as observers

from aircraft, and of air officers as observers

with ground forces, is vital to progress in

this field. And that progress is vital to the

Army,

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Carl Dreher (Article Writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1942-02

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

82-89

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google Digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Roberto Meneghetti

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 140, n. 2, 1942

Popular Science Monthly, v. 140, n. 2, 1942