-

Titolo

-

U. S. best flyers' training

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Selection, training, integration - three reason why we have the world's best flyers

-

extracted text

-

"OUR FLYERS are the best in the

world!"

So says General H. H. Arnold, com-

mander of the U. §. Army Air Forces, Flat

statements from Arnold are rare. He is as

cautious in speech as he is daring in tactics.

He made the statement to a graduating

class at Randolph Field a year and six days

after Pearl Harbor. The commander had

adequate time to draw a real conclusion.

Then he quoted the score to prove it.

From February 1 to December 5, 1042, the

Army Air Forces had destroyed 928 enemy

aircraft, losing but 234 of their own; an

all-over advantage of nearly four to one.

Consider the fact that most of our air-

men lacked previous combat experience,

and faced air organizations seasoned by

three to five years of actual warfare.

What is it then, that our flyers have

that qualifies them to remain alive in the

face of this superior experience, and to

roll up overwhelming evidence of personal

superiority ?

Some theorists claim that the average

American is physically and psychologically

superior to the typical Axis warrior. Our

practical militarists prefer to let Herr

Goebbels carry the propaganda ball for

the super race, while we build a super air |

force from plain average-run Yanks.

Leaving the Superman theory to Axis

prevaricators and comic-book artists, it is

possible to trace the military margin to

more prosaic reasons; selection, training, |

and integration.

Our pilots have more flying time before

they get a look at the enemy than most |

Axis airmen have before they are finally

shoveled under. The typical Yankee combat

pilot has 200 flying hours in primary, basic, |

and advanced training; 100 more in transi-

tional schools; 200 in operational schools; |

and a final polishing off right behind the

theater of combat to fit him into the local |

military conditions. In the 1918 scrap, pilots |

were sent into battle with about 90 hours,

to face veterans of three years’ combat. |

The Germans knocked them down with both

hands. This trip it is different.

Typical of the reports on the results of

our training is one that came back with

the 19th Bombardment Group, home from

Australia. For several anxious months, 48

Flying Fortresses had held the balance be-

tween success and failure in Japan's at-

tempt to invade the down-under continent.

Now that proper reinforcements have been

sent there, and the war-tired veterans

brought home to spread their experience

among the younger airmen, it is safe to

tell how thin that red line was between

ourselves and defeat. While it would be

unjust to state that these 48 crews, unaided,

held off attack, their constant pounding of

Rabaul and other points probably set the

Japs off balance so that a full-scale jump

onto the continent was impossible.

The total score of these craft that oper-

ated unaided by fighters may be remem-

bered as long as airmen fight in the sky.

Most Americans reading in dispatches from

Australia before last November that Gen-

eral MacArthur's Fortresses had again

raided Jap installations in New Guinea, pic-

tured swarms of four-engined Boeing B-17's

leaping out of carefully constructed, mirac-

ulously camouflaged runways, to pound

Rabaul again and again.

It wasn't that way. MacAr-

thur's Fortresses were for many

‘months a mere four dozen, many

of them patched from wrecks

dragged out of the Philippines.

They were kept in the air with

Yankee ingenuity, defended on

the ground with plain guts, and

kept potentially dangerous by the

best training and teamwork ever

known to mankind. They were

attacked with the best fighter

equipment the Mikado could con-

Jure up. Still the Fortresses re-

mained as the outer rampart of

the continent. Now, amply re-

inforced, Australia appears im-

pregnable.

The evidence piles up that Gen-

eral Arnold is right. As the final

scores are tabulated the total in-

dicates that the four-to-one ad-

vantage is holding and growing

greater. The margin of superi-

ority holds and holds well. Why?

We, as a nation, are willing to

spend the money for adequate

training. While time is carefully

doled out and every tick of the

cadet’s clock put to work, we

have skimped no material and

effort to give our airmen the best

possible chance of survival and

victory. Our selection for air

training is made strictly on merit

and performance. Compare this with the

German system where the first requisite

for nomination to the Luftwaffe is race and

political connection. In Nippon, selection

is made by family.

Like the aircraft they fly, our airmen’s

superiority comes first from the selection

of proper materials. Making silk purses

from sow’s ears and pilots from ninnies or

ham-fisted thickskulls is equally disappoint-

ing work. The Air Force's first job is to

get men who are first-rate timber.

The cadet selection board takes the first

step in the necessary weeding out. The

basic primary physical requirements are

well known. A good airman must have the

stamina to stand up to the physical wallop

that aviation gives the human frame. The

innovation is in the psychological factors

involved: is the man men-

tally equipped to fly? If so, what kind of

flying will he be good at? Does he belong

in the cockpit at all, or at the navigator’

table or lying flat on his stomach operating

our precious bombsight ?

The young American, below the age of

27, in good health and possessing at least a

high-school education or better, applies to

his local cadet selection board with three

letters of recommendation from persons of

standing in his community. He undergoes a

physical examination similar to that given

any officer candidate. Subsequent tests tell

more about his personal qualities and quali-

fications than any number of diplomas or

letters of recommendation, however detailed.

They show exactly where he stands in the

things that the Army needs in its flyers.

The most important fact which the primary

psychological search tries to determine is

whether the cadet candidate is mentally

equipped to learn—whether he can absorb

the complex information about to be flung

at him completely, accurately, and in the

short time which the war emergency pro-

vides for him.

This qualifying exam has proved so ac-

curate that the two-year college require-

ment, previously held as absolutely neces-

sary, has now been virtually abandoned.

Actual military experience indicates that,

in many cases, a purely academic attitude

may Kill the very instinct that makes an

audacious pilot, an imperturbable bom.

bardier, or a nerveless navigator.

The primary examination has been rigged

Dy the psychologists to determine whether

the candidate has the basic stuff of which

Afr Force personnel is to be formed. Can

he comprehend instructions? Can he size

up new and unfamiliar materials and situ-

ations? Can he follow directions accurately

without lengthy auxiliary explanations? His

judgment must be dependable, his sense

of organization flawless. The qualifying

exam weeds out most of the unfits, but

the dangerous job of weeding out the bor-

der-line cases comes farther along the line.

Once appointed, the men are moved along

to the reception centers, where they are

sorted out to determine just what job they

will hold later on. Commissioned air-crew

members are divided into three classes of

activity; bombardiers, pilots, and naviga-

tors. There was a time when men who

were unable to make the grade as pilots

were trained to hold the other two posts.

Psychologically, this was a poor system, a

relic of World War I. In spite of itself, it

produced some excellent air-crew members,

simply because the basic requirements for

navigator and bombardier differed so vastly

from that of the pilot that there was a good

chance that if the man flunked out in his

flight checks, be had what it took for one

of the other two air posts.

‘The bombardier requires excellent hand-

eye co-ordination, superior finger dexterity,

great motor steadiness, and the ability to

‘make complex calculations under conditions

of the utmost stress. In addition to this,

Be must have sufficient mechanical aptitude

to operate the complicated bombsight.

A pilot, on the other hand, must be able

to absorb the complex motor skills involved

in fying, the physical business of getting

one’s hands and feet together and in perfect

rhythmic movement, to go through the

complex motions required in flying the

modern airplane. He must demonstrate

superior reaction time and an ability to

make quick, accurate observations, and

possess a certain cockyness required for

combat. The fighter pilot should, in addi-

tion, possess a certain “killer instinct” that

makes him different from other pilots or

alr-crew members.

The navigator, on the other hand, must

De the imperturbable pedant of the crew.

Besides the prerequisite flair for mathe.

‘matics, he must possess not only the motor

co-ordination required for the handling of

‘navigation instruments, but also a calmness

that permits him to continue his calcula~

tions despite setbacks and interruptions.

A battery of tests awaits the cadet when

he arrives at one of the reception centers.

His case history, his childhood, and his edu-

cation are carefully checked into. Another

written examination follows, but the bur-

den of the physio-psychological determina.

tion of what he is good for is bone by

apparatus tests which determine which

of the three jobs, if any, he is good for.

The apparatus is purposely deceiving, so

that no ambitious kid fitted for the navi

gator’s post may deliberately flunk his way

into flying school.

There are no hard-and-fast rules about

selection. The psychologists are working on

new examinations all the time, and when

new tests are rigged and found to be more

accurate, they are placed in the examina-

tions, supplementing or replacing those

in use. For instance, there is the simple

peg-turning test. Students are placed at a

board in which are set rows of pegs. Half

the peg tops are painted black, the other

half white. The student is instructed to

turn each ome 180 degrees. The time and

accuracy are clocked and recorded. A simi-

lar test of moving pegs from one board to

another a full arm's length away, checks

arm and hand dexterity.

Discrimination reaction time is tested by

red and green lights placed on a board in

front of a seated student. Certain combina-

tions are extinguished by switches at the

student’s hand. When

the cadet gets the

right switch to match

the combination, a

white signal light

goes out. The factor

recorded is the

amount of time it

takes the cadet to

extinguish the white

light in 50 tries.

Serial reaction

time is another char-

acteristic which the

psychological lab

tests with great in-

terest. Its rig seats

the cadet at a set of

dummy airplane con-

trols, stick and rud-

der, in front of a

board on which a set

of light buttons de-

scribe the three-di-

mensional motions

of a plane in flight.

The lights are set in

two rows, one red

and one green. The

lines of lights de-

scribe a curve across

the top for bank or side-to-side motion of

the stick, up and down for the stick’s for-

ward and back movement which represents

nose up or down in the plane. A straight

horizontal set records the movements with

the rudder bar. With a complicated set of

electrical switches, the examiner flashes a

control position, indicating it with one set

of lights. The student must then bring

the controls into such a position as to light

the set of buttons opposite those already

lit. The reaction time and accuracy is

tested.

Most cadets think this test is exclusively

for testing prospective pilot ability. Actu-

ally no one test determines a final selec-

tion. This piece of apparatus merely indi-

cates how well a cadet can get his hands

and feet to act in unison to produce a de-

sired effect under pressure. Many a bud-

ding pilot has been “thrown” by this hurdle,

fearing lest this was the final test whether

he was to fly, navigate, or bomb.

Steady hands are a prerequisite in all

three posts in a bomber. The pilot must

be able to fly a straight course to an objec-

tive through a hail of antiaircraft fire in

the final bomb run. The bombardier must

lie and manipulate his sight while the rest

of the crew mans machine guns to ward

off the attack; the navigator must hold the

sextant in untrembling hands when all his

precalculated courses are shot to the devil

by adverse weather

or military condi-

tions.

The cadet is seated

at a tiny box in

whose cover is a nail

hole. He is handed a

charged metal sty-

lus and told to insert

it in the hole and

hold it steady, with-

out touching the

sides. If a contact is

made, the circuit is

closed and a point

is recorded against

the student. Fore-

warning the student

as to what is going

to happen has little

or no effect on the

result. He sits down,

determined to hold

steady, come what

may. Then a non-

commissioned officer

sneaks up behind

him murmuring such

words of encourage-

ment as, “So you

think you'll be able

to fly, flutterfingers—why, you cluck, there

are better heads than yours on cabbages.

If you can’t hold still now, what'll you do

when the ack-ack starts shooting?” Then a.

bunch of scrap-metal hung from the ceil-

ing in the opposite room is dropped with a

sound like the crack of doom, or a klaxon

is sounded close to the cadets ear. No

one is perfect on this test, but a low-failure

score on this test is a good indication.

Bimanual co-ordination, the art of get-

ting each hand to work at a separate job

to achieve a single unified result, is gauged

by another test. If you don’t think this

requires skill, try this simple test on your-

self: place your left hand on top of your

head, your right on your stomach. Rub

your head with a circular motion, your

Stomach crosswise. Then try speeding up

the circular motion on the head and revers-

ing direction without breaking either the

rhythm or direction of the right hand. This

kind of co-ordination is essential in many

of the air-crew jobs. The newest piece of

equipment to test this is the lathe-type

tester. It consists of a flat, rotating disk

like a phonograph turntable, over which

rides a sliding arm with a dual-direction

stylus. The movements of this stylus are

controlled by two wheels, similar to those

on a lathe. There is a spot on the disk,

whose motion, direction, and rate of travel

are highly erratic. The cadet is supposed

to keep the stylus in contact with the spot

by means of two wheels. The examiners

record the number of times the cadet loses

contact with the spot.

New tests are introduced continually,

not only because the psychological division

is extremely progressive, but also because

frequent discussion of the tests between

students may rob them of their effective-

ness. - Certain tests must be a surprise to

be effective; others remain standard for a

long time.

At the reception centers, the students are

given a chance to register their prefer-

ences in assignments. In the beginning,

there was a mass rush toward the pilot

appointment, but a well-organized cadet-

relations program has convinced many stu-

dents that the man who flies the plane is

just the aerial hack driver, and increasing

numbers bid for navigator or bombardier as

first choice.

Wherever possible, the student is given

his choice of assignments. In horder-line

cases, his preference is the deciding factor.

Nevertheless, if he shows marked tenden-

cies toward navigation, has the necessary

education, and has the systematic mathe-

matical mind required for such a job, he is

counseled to accept this appointment.

Once the selection is made, the cadets are

sent to Army preflight schools for nine

weeks of Army education. Pilot candidates

then move off to established Army primary

flying schools to absorb the rudiments of

flying.

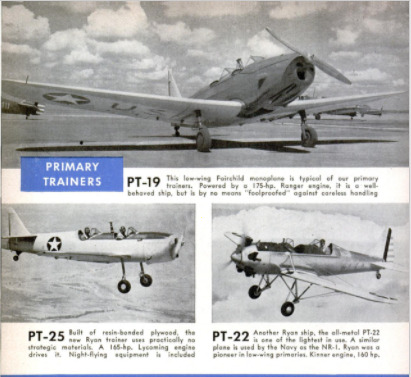

Here the cadet makes the acquaintance

of the PT series, a rugged group of pri-

mary trainers designed to give the pilot his

aeronautical ABC's. He learns to taxi, take

off, fly straight, climb, turn, glide, and

land. He learns to land with and without

power, upwind and crosswind. He learns

to spiral and side slip; to stall the plane,

power-off and power-on; to spin and re-

cover. During this procedure, acrobatics

are stressed, along with steep turns and

chandelles.

The thing that makes our elementary

flight training unique is the type of equip-

ment we use, from the very beginning. The

line of U. 8. primary trainers includes the

Stearman, Fairchild, Ryan, and others. The

lowest powered of these ships carries 165

hp. The average is 210; some even run 265.

Italy's average primary trainer is powered

by ‘a 100-hp. engine, Germany's average

runs 90, and Britain's is in the 135 bracket,

while Japan's primary trainers are reported

to carry somewhere in the neighborhood of

85.

American instruction is based on co-

ordination and judgment. It is built on the

idea that the military pilot is destined to

fly airplanes with power enough to get him

into trouble if he fails to respect it—and to

get him out if he handles it right.

The popular Fairchild PT-19, a low-wing

monoplane powered by a 175-hp., six-in-line

Ranger engine, is typical of the Army's

trainers. A well-behaved airplane, it Te-

sponds obediently to controls, exhibits no

control trickiness or flying vices of any

kind. On the other hand, no advanced aero-

dynamics have been built into the airplane

to compensate for students’ sloppiness in

flight technique. The Fairchild is built with

a sturdy, welded, steel-tube fuselage. Its

wings are of resin-bonded spruce, fabric-

covered. Unlike most primary trainers, the

PT-19 is equipped with a flap or air brake;

not that its landing speed requires it, but

because some instructors think that its use

should be made part of the flying routine

early in the cadet's career.

The newest of the trainer series, the Ryan

PT-25, a ship built entirely of resin-bonded

Plywood, also has a flap. Many of the pri-

maries, however, still retain the old-fash-

ioned biplane rig. Orthodox builders find it

easier to incorporate the basic requirements

for this ship—stamina—into the two-wing

design. These types include the PT-15, the

St. Louis trainer, powered by a 225-hp.

Wright Whirlwind; Stearman‘s PT-13, pow-

ered by a 225 Lycoming radial; 17 and 18,

which are identical except for thelr power

plants—the 220-hp. Continental and the

225 Jacobs. The Waco PT-14, powered usu-

ally with a 220 Continental is also in wide

use. The lightest in the series are the

Myers, a small biplane powered by a 145

Warner engine, and the Ryan PT-22, pow-

ered by a 160-bp. Kinner engine. Both of

these ships are of all-metal construction.

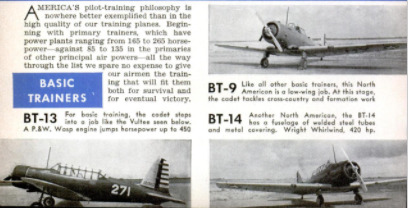

The next jump is into basic training air-

planes. All of these are low-wing mono-

planes. The power is suddenly doubled.

Sensitive flaps, landing flaps, and a con-

trollable-piteh propeller add considerably to

the pilot's woes. Most of these ships are all

metal, weigh over two tons fully loaded,

‘and are equipped with a panel full of instru:

ments and two-way radio. Here the cadet

learns instrument flying, cross-country fly-

ing, and primary formation fying. Here he

puts into practice the ground-school educa-

tion—navigation, meteorology, code and

volce communications that have been

pounded into his cranium between fights.

The most commonly used equipment in

this class is the North American BT-l4,

powered by a 420-hp. Wright Whirlwind

engine. This ship has a remarkably tough

structure. Like the average primary, its

fuselage is built of welded steel tubes, but

the outer surfaces are fabric-covered alumi-

num sections

bolted to the fuselage. The ship cruises at

about 150 m.p.h. and has a range of 600

miles. In the same general class are the

Vultee, the BT-13 and 15, similar designs

powered respectively with 450-hp. Pratt &

Whitney Wasp and 420 Wright Whirlwind

engines.

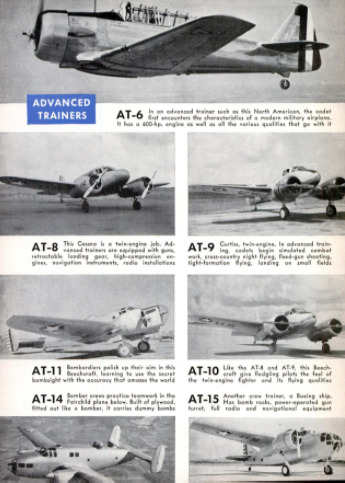

Tn the advanced trainer, flying takes on

a serious military aspect. This ship has

most of the characteristics of a full-grown

military airplane—guns, retractable land-

ing gear, high-compression engines, full

navigational instruments, complete radio.

Here the cadet begins simulated combat

training during the day and cross-country

at night. He flies tight formation, lands in

small, unfamiliar fields, shoots the trainer's

fixed guns, gets the theory of combat, and

is further indoctrinated in the science of

air warfare. The North American AT-6 has

been currently standardized for this job,

and turned out in large volume production.

This ship is reputed to be the toughest air-

plane ever built, structurally and opera-

tionally. Its wing is all aluminum alloy,

with two spars in its center section and one

in the outboard panels. Still being a trainer,

it bears the last semblance of the steel.

tube structure in a part of the fuselage up

to the back cockpit. No great effort has

been made to make this ship easy to fly.

While it is no man-killer, it contains all the

potential headaches of fighting ships but in

a lesser degree. The AT-6 has a 600-hp.

engine and all the grief that comes with it.

The cadet learns to baby his engine after

take-off, the art of getting the maximum

performance out of his power plant on long

cross-country flights. He has learned ad-

vance aerobatics, elementary gunnery. In

the primary and basic types, the cadet has

learned to be a pilot; in the AT series he

learns to be a sky soldier.

By the time the student completes Ad-

vanced Training, his instructors know what

kind of pilot he is going to be. The pursuit-

talented kids go off to their particular type

of advanced and operational training, the

bombers go to be molded into an integrated

crew.

Basic combat trainers are merely AT's

armed with four .30 caliber fixed machine

guns and a couple of camera guns. The

pursuit pilot's life from this point on is

filled with aerobatics and gunnery. He

graduates to obsolescent P-40's and is final-

ly polished off in the latest equipment,

taught operations, and sent to a combat unit

which finally teaches him local conditions

whose acquaintance is the price of survival.

The bombardment-pilot cadet has, in the

meantime, joined up with units handling

twin-engined trainers which first give him

the rudiments of multi-engined ships. The

Curtiss AT-9 and the Cessna AT-17 teach

him the fine art of engine synchronization,

how to fly with one engine dead, and the

complicated procedures of handling engines,

props, flaps, and the 13 other major con-

siderations in taking off and landing larger

ships. Furthermore, he learns the art of

dividing the job with a copilot. In the

meantime, other members of the air crew

have been selected and trained. The officer

members he left behind in the classification

centers as bombardier and navigator join

up at this point.

The secrecy that shrouds the bombsight

prevents discussion of the bombardier’s

training, but it should suffice to say that

these lads can hit a pickle barrel from

10,000 feet. They have gotten most of their

practice in the Beechcraft AT-11s, a twin-

engined job powered by 450-hp. Pratt &

Whitney Wasps. The navigator's time has

been spent chiefly in the AT-7, similar to

the 11, lacking only the bombardier’s nose.

The next step is into crew trainers. Here

the other members of the bomber’s crew—

radio operator, flight engineer, and ar-

morer—are added. These men are non-

commissioned officers, graduated from the

special schools of the Air Forces Tech-

nical Training Command. Specialists in

their individual fields, they were found

physically and temperamentally fit to be

air-crew members, and, after completing

their specialized ground training, were sent

to gunnery schools to learn the art of

handling the free and turret-mounted .50

caliber machine guns that arm our bombers.

The bombardier and navigator also got

flexible gunnery practice, 50 that they can

man their posts when the bomber goes into

combat.

From the crew trainers, the men enter

the ships in which they will finally face the

enemy. Veterans, back from combat units

(we have some after a year of war), give

the new crews the latest dope on combat

and survival. Then they are shipped off to

the theaters of war. They are not, how-

ever, flung into battle immediately. The

process of indoctrination continues. Opera-

tional training under escort, in formation

with veterans of the area, gives the new

men the feel of being artists in destruction.

-

Autore secondario

-

William S. Friedman (Article Writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1943-04

-

pagine

-

96-102, 210, 212

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google Digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)