-

Titolo

-

The making of U. S. air gunners

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: Flying sharpshooters

-

Subtitle: Here's what happens in the five week that turn a green hand into a crack air gunner

-

extracted text

-

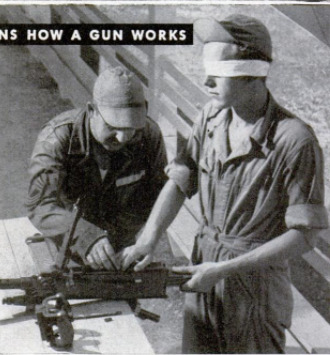

WHEN you read of American aerial

gunners scoring amazing victories

over Axis fighters, do so with the realiza-

tion that many of them, only a few months

ago, had never even

seen a machine gun.

Intensive, thorough

training has given

them the skill of vet-

eran air fighters.

Our gunners fortu-

nately are blessed with good shooting eyes.

They spring from fathers who have handled

rifles since early boyhood. Even without

long, hard training in the art of shooting,

they're more than a" fair match for our

enemies.

But I'd like to present an even more en-

couraging picture. Recently I spent several

days at McCarran Field near Las Vegas,

Nev., one of the Army's schools for train-

ing in flexible gunnery. There I observed

“students, all volunteers, in every stage of

the rigorous five-week course as youngsters

fresh from replacement centers labored and

sweated to win their precious sergeant’s

stripes and gunner's wings. There I ob-

served in the making the smashing victories

that will make tomorrow's news headlines.

Talk to any gunner who has experienced

the withering fire of a German or Jap, and

he'll tell you our boys are better than their

opponents.

Sergt. Hamilton Moore rode the clatter-

ing tail of a Flying

Fortress to help beat

back the Jap fleet at

Midway. Together

with Paul Johnson, a

staff sergeant man-

. ning the upper turret,

he knocked off four Zeros on one flight,

filling them with .50 calibers at 300 to 450

yards. Moore and Johnson went up with

1,200 rounds of ammunition, came down

with 800 remaining in their belts. Four

hundred rounds, four Zeros!

From every front, word comes back to

the schools that American gunners are

taking a terrific toll of the enemy. The

guns of a Flying Fortress dropped three

Sento Zero Zeros off Alaska in six secfnds.

Over France a Fortress exploded a German

fighter at 1,200 yards, a distance normally

considered beyond the effective range for

the .50 calibers.

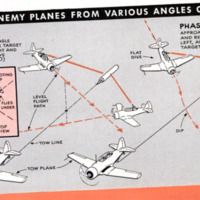

When a gunner roars into combat, his

shooting job calls for the automatic solu-

tion of several triangles. Were he to halt

for even a second to think about the prob-

lems, the enemy might shoot down the

bomber he's guarding.

Psychologists are just now taking over

the vastly important job of conditioning

him for such moments. Every one of the

35 days in gunnery school witnesses one

more strand of the pattern woven into

training and habits.

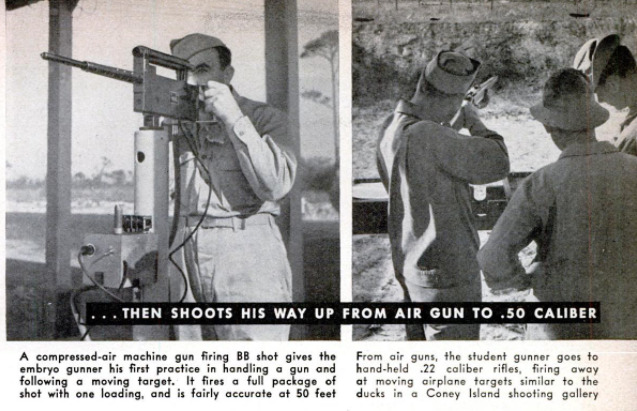

You'd be amazed to see recruits awk-

wardly fingering a BB gun one Monday

and tossing off glibly five weeks later such

terms as exterior ballistics, apparent speed,

and range estimation, then winding up with

a sharpshooting demonstration by plug-

ging a fluttering white target from the

after cockpit of a gunnery plane or the

belly turret of a Fortress.

What has occurred meanwhile? First,

they have learned by trapshooting to aim

and lead a target, winging clay birds as

they speed straight away, to right and left.

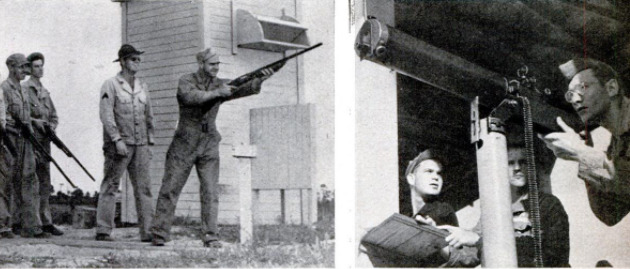

Then, on a moving-base range, they con-

tinue skeet-shooting from trucks bumping

15 miles an hour around a mile-long track.

Now the birds wing in all directions. A

good shot will hit ten out of 25 during his

first round.

Aim, lead, and fire. That's the eternal pat-

tern. Now the embryo gunner advances to

hand-held .30 caliber machine guns. He

looks across an oval track, around which a

gas-powered car carries a white target,

passing alternately 100 and 400 yards from

the guns. Aim high, lead, and fire. Painted

bullets will reveal the score.

Near by the boys practice range estima-

tion, peering through standard sights along

wooden guns mounted on a long railing.

Every minute or so an attack plane roars

in, swishing past their sights only 50 feet

up. Over the radio they hear: “One mile

. . . one thousand feet . . . eight hundred

... six hundred . . . four hundred . . . two

hundred.” Shortly every man on the line

knows how that 60-foot span looks in his

ring sight at all ranges.

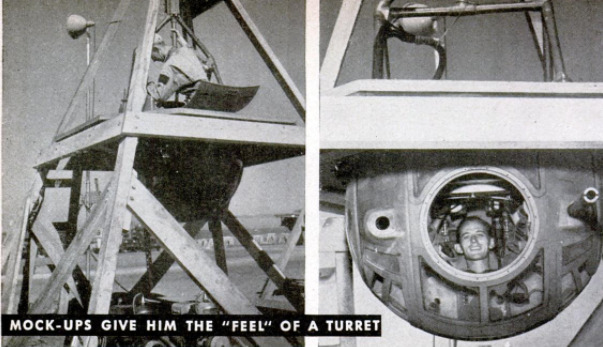

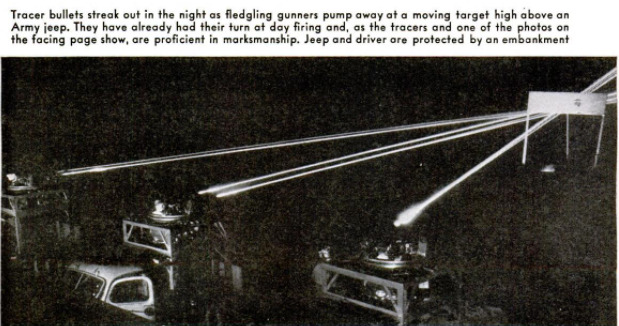

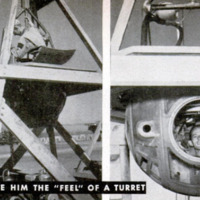

Now the boys get their first taste of the

big 50's. They crawl awkwardly into

powered turrets—the kind they'll fight from

in the Fortresses and Liberators—mounted

on heavy trucks, and train their weapons

on the same white targets. You note they

wait longer before touching the triggers,

and fire shorter bursts. They want every

possible shot to count.

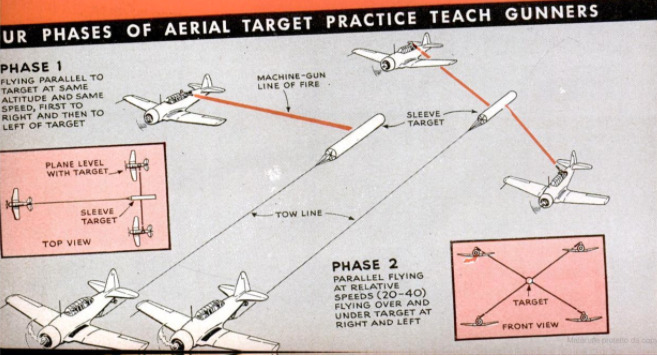

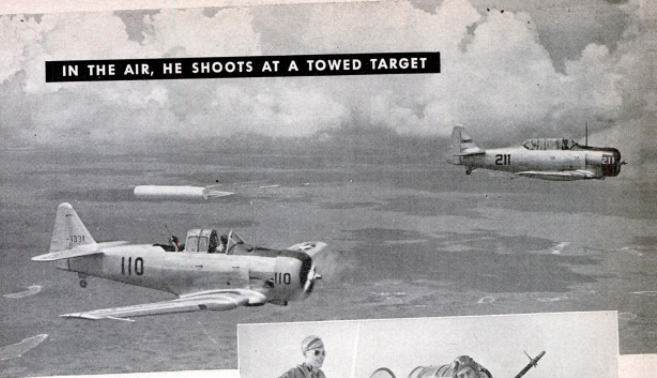

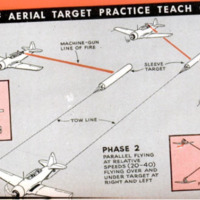

During the final week, having mastered

ground-range firing, from both swivel-

mounted and turret guns, the students

climb daily into planes for aerial firing.

Those Who pass successfully receive com-

bat-crew wings and sergeant's stripes, and

are assigned to teams for final training

before going into action.

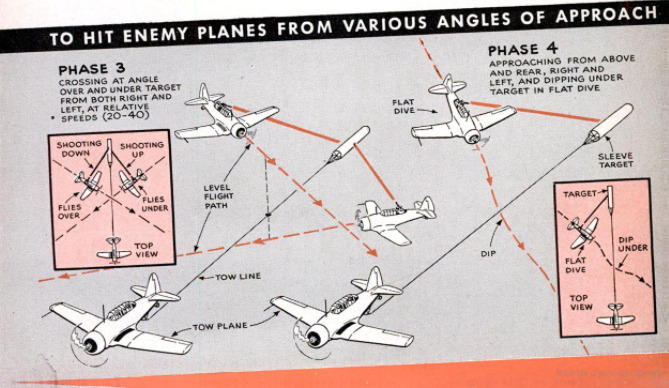

How well a gunner performs in combat

depends both upon his training and the ring

sight through which he views the darting

enemy plane. He times the target across,

and the angles take care of themselves.

This adds up to what he knows as rela-

tive or apparent speed, determination of

which requires that he know the range and

the length of time required for a target

moving at a definite speed to cross the ring.

As he grows more familiar with various

approaches in aerial combat, he is able to

estimate that speed by observing only mo-

mentarily the fight of a plane across his

ring.

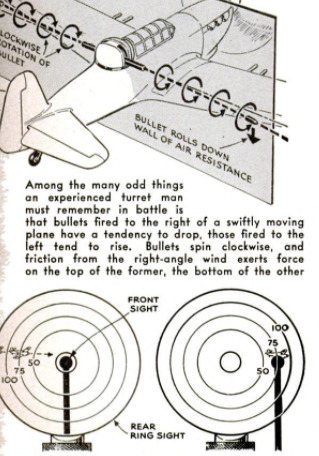

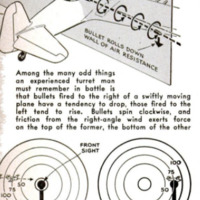

‘Another reason why aerial gunners must

undergo rigid training is that bullets don't

behave as they would if fired in the still

air of an indoor range from a stationary

‘position into a stationary target. Not only

does gravity pull a 50 caliber projectile

down and air resistance hold it back by

measurable amounts which vary with alti-

tude, but the surrounding air causes the

bullet to drift upward when fired to the

left of the plane, right when shot upward,

down when discharged to the right, and

left when shot downward.

Too, the very rush of the plane forward

imparts a sideways movement to the bullet

until air resistance causes it to straighten

out and actually lag behind the firing plane.

Wind rushing past further complicates

aim, bringing into play a third factor called

ballistic deflection. This means the gunner

must actually lead the target by an addi-

tional amount, depending upon the angle

at which he fires.

Few military experts thought two years

ago that aerial gunnery as exemplified by

American crack shots would account for a

high percentage of hits at ranges exceeding.

a half mile. Then the 50's commenc:

proving their worth, Germans and Japs

became wary of moving in too close, and

air battles raged with fighters pot-shooting.

from 600, $00, and 1.000 yar, sweeping in

for quick passes at closer ranges. But the

50 caliber is still deadly against these tac-

tics. With a well-trained man behind it,

it can throw 400 to 600 slugs a minute into

a hat at 3,000 feet. And that's shooting!

-

Autore secondario

-

Andrew R. Boone (Article Writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1943-04

-

pagine

-

118-125

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google Digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Schermata 2022-02-23 alle 15.01.30.png

Schermata 2022-02-23 alle 15.01.30.png Schermata 2022-02-23 alle 15.01.35.png

Schermata 2022-02-23 alle 15.01.35.png Schermata 2022-02-23 alle 15.01.42.png

Schermata 2022-02-23 alle 15.01.42.png Schermata 2022-02-23 alle 15.01.54.png

Schermata 2022-02-23 alle 15.01.54.png Schermata 2022-02-23 alle 15.02.02.png

Schermata 2022-02-23 alle 15.02.02.png Schermata 2022-02-23 alle 15.02.08.png

Schermata 2022-02-23 alle 15.02.08.png Schermata 2022-02-23 alle 15.02.22.png

Schermata 2022-02-23 alle 15.02.22.png Schermata 2022-02-23 alle 15.02.40.png

Schermata 2022-02-23 alle 15.02.40.png Schermata 2022-02-23 alle 15.02.45.png

Schermata 2022-02-23 alle 15.02.45.png Schermata 2022-02-23 alle 15.02.51.png

Schermata 2022-02-23 alle 15.02.51.png Schermata 2022-02-23 alle 15.02.57.png

Schermata 2022-02-23 alle 15.02.57.png