-

Titolo

-

U. S. troops on armored transports

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: Troops on wheels

-

Subtitle: A modern cavalryman is a rough-riding, hard-hitting member of a tiny task force that does a big job

-

extracted text

-

WHEN America’s new Army swung in-

to action against the Nazi foe in

North Africa, and on every important fight-

ing ground since, our battling divisions went

into combat behind a fast-moving screen of

highly trained mechanized cavalry—scout-

ing the enemy, probing delicately for his

strengths and weaknesses, pouring back a

flood of vital information that enabled our

commanders to dispose their troops to the

best advantage.

This reconnaissance screen performs one

of the most important services in war. The

men who handle these missions are among

the toughest, bravest, and smartest troops

we can boast, and they are carrying on a

proud tradition of American arms.

For today’s U.S. cavalryman wears the

crossed-sabers emblem on his uniform as

proudly as any swashbuckling trooper of

the glamorous past, although the weapon

he yanks out of his leather scabbard is more

likely to be a Tommy gun than a saber, and

the scabbard itself is slung on a burly mo-

toreycle or a go-anywhere jeep.

True, our Army still has crack horse out-

fits for specialized work, but cavalry in

modern war is mainly mechanized, and its

basic function is reconnaissance rather than

combat—even though the nature of their

work requires cavalry detachments to be

among the fightingest units in any army.

The cavalryman in battle lives a life that

can only be described as full and active. He

operates as part of a miniature task force,

usually well in advance of the main body

of troops or far out on the flanks, often as

much as 50, 80, or 100 miles behind the

enemy's forward positions.

His is a slashing action—quick penetra-

tion of border or road guards, a headlong

dash down side roads or trails, a blasting

exchange of fire with an enemy strong

point or counter-reconnaissance patrol.

Then in a moment he becomes a stealthy

intruder, horsing his vehicles up into the

brush or woodland, hiding them under trees,

putting out cat-footing patrols to probe for

hostile encampments in the dark.

Always the cavalryman concentrates on

getting the information, protecting it, and

getting it back to the command post. In ful-

filing his duties he must be tough as a

commando and smart as a G-2 officer.

Mechanized cavalry units go into action

plentiully supplied with technical tools—

Vebicles, weapons, and radio equipment.

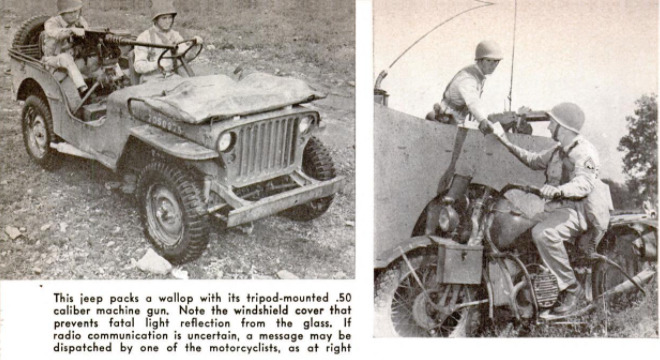

Their’ basic roiling stock includes the

powerful armored scout car and the Army's

Dew shaft-driven motorcycles, as well as

the handy midget cars best known to the

public as jeeps, although cavalrymen are

more likely to call them “bantams” or

“quarter-tons.”

Reconnaissance details have thelr own

“heavy artillery” n the form of hard-punch-

ing 37-mm. antitank guns and 81mm. mor-

tars. The cars also carry heavy and light

machine guns, which, added to the rifles,

carbines, and submachine guns of the me,

20d up to & very respectable fire power.

Other weapons include ground mines, smoke

and gas charges, and demolition kits with

TNT charges, fuses, and detonating cord.

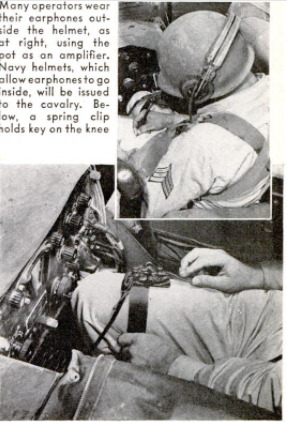

Radio communication naturally is the

heart and soul of fast reconnaissance work.

Cavalrymen working deep in enemy terri.

tory can feed & steady flow of reports to

headquarters by means of the powerful

Signal Corps code transmitters mounted In

scout cars. For shorter distances, and par-

ticularly for advance reconnaissance when

the heavier vehicles are ia concealment and

small observation parties go out In Jeeps or

on foot, the cavalry has a portable receiver

transmitter of special design, working with

voice transmission.

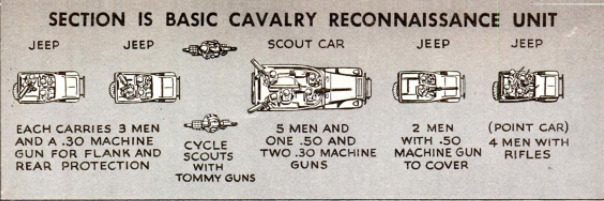

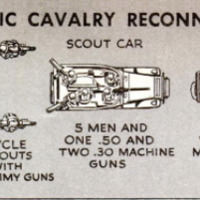

"The basic unit of organization for mecha.

nized cavalry is the section, made up of a

scout car, four Jeeps, and two motorcycles.

Two sections make a platoon, regarded as

the main tactical unit in reconnaissance

tactics, while three of these platoons make

a troop

A reconnaissance troop is assigned to

each triangular infantry division, while each

of our motorized divisions has a full “recon”

squadron—three regular troops, an armored

support troop, and a headquarters troop.

Headquarters troop handles such matters

as supply, administration, communications,

and motor maintenance. The support troop

is designed as a heavyweight outfit, with

15 to 20 hard-hitting combat vehicles of the

tank type, plus various supplementary cars.

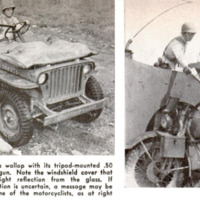

A typical arrangement of a section oper-

ating on a road might find the scout car

preceded by two jeeps and followed by the

motorcyclists and the remaining two jeeps.

The lead jeep, functioning as a point car,

carries a driver and three riflemen, and is

covered and protected by the second jeep,

with two men and a .50 caliber machine gun.

‘The scout car, carrying the section com-

mander, has light armor plate and packs a

punch with a .50 and two .30 caliber ma~

chine guns. The cyclists normally stay close

to the commander, ready to dart ahead or

into a side road on short scouting missions,

or to whirl around and head back to deliver

messages or warn following units of danger.

Each of the two jeeps at the rear carries

three men and a .30 caliber machine gun.

Their main mission is flank protection and

reconnaissance. In an operation where en-

emy heavy units may be encountered—

tanks, mobile assault guns, armored cars,

and the like—one of the rear jeeps probably

would be assigned to tow a 37-mm. antitank

gun.

This road arrangement is capable of wide

variation, of course. If the outfit hopes to

smash through light enemy resistance at

high speed and move on into open territory,

the scout car may lead the way. This means

running the risk of road mines or concealed

artillery, yet in some circumstances the ad-

vantage to be gained might be worth the

try.

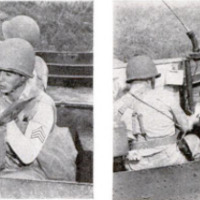

Obviously, it takes cracking good soldiers

to carry out these missions, with their wide

range from head-on combat to stealthy

scouting. Cavalrymen are good and they

look it—tough and businesslike in the drab

greenish-gray coveralls which serve as their

battle dress. They are quiet and watchful,

as befits troops who may be spending a good

deal of their time in enemy territory. They

are the kind of soldiers who carry their

weapons along to mess, and disperse under

the trees to eat without being reminded

of it.

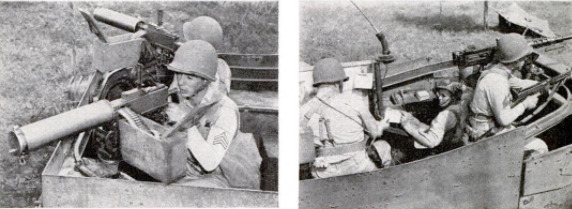

The teamwork required in a scout car and

the supporting elements of a section rivals

that of a heavy bomber crew. The com-

mander, to begin with, must have expert

knowledge of all his vehicles, weapons, and

communications equipment, and of the en-

emy’s as well. He must be expert at visual

reconnaissance, have a sound understanding

of intelligence problems to make his reports

to headquarters of maximum value, and

know methods of supply and techniques of

construction well enough to do a swift and

efficient job of demolition if the chance

arises during a sweep through hostile ter-

ritory.

In’ addition, the cavalry leader must have

a good grip on basic infantry combat tac-

tics, as well as the specialized tactics of his

own branch. And he must have a thorough

knowledge of maps, navigation, and orlentn-

tion problems. This latter qualification came

to the fore especially throughout the desert

fighting in North Africa, where many

sweeps of hundreds of mile were carried

out over the trackless sands, depending en-

tirely on compass readings, dead reckoning,

and celestial observations.

The more of these skills a trooper ac-

quires, the better all-around cavalryman he

becomes, although naturally his primary

concern must be his own specialties In the

team setup. Thus the driver's first concern

must be his combat vehicle. Ho has to he

able to handle it across any going from a

concrete highway to a shallow creek and

perform the elementary repairs and main-

tenance the Army classes as “first echelon.”

‘Aside from that, he must know the ways

of camouflage and concealment. Ho must

have a hair-trigger reaction to signals and

commands, and must blend with the other

vehicles on the road as a good taxi driver

blends with fast-moving traffic, anticipating

what the other drivers are going to do.

The cavalrymen who ride the bucking

Jeep must be ready to function as the point

of the column, and keep a wary eye on the

road for buried mines—one of the mechan-

176d troopers’ worst hazards, They must

know how to read maps and keep them-

selves oriented at all times, and must have

special preparation for effective reconnais-

nance, including the ability to Judge num-

bers of men and vehicles on a road, the

approximate size of enemy camps, and the

difference between the enemy's special types

of heavy and light artillery, or heavy and

medium tanks. They must also be expert

Fiflemen and machine gunners, able to lay

down un effective harassing oF covering fire.

Motorcycle scouts ure as tough and handy

ax any men in our Army. It is scarcely pos-

sible to overestimate the courage and physi-

cal ‘stamina Jt takes to chaufteur one of

nese over-powered, war-going kiddie cars

down pounding hard routs, over washboard

or corduroy wurtace, dodging boulders, and

Withering through sandpits, while the other

men of the section enjoy the comparative

luxury of squatting on a steel storage well

and clinging to the relatively stable business

end of 30 caliber machine gun.

“The cyclist is above all clse a road agent

Rot in the old-time sense of the dashing

outlaw who held up stage coaches, but in

new technique of swift investigation of side

roads and suspicious terrain ahead. A motor-

Cyclo can do this Job faster than any other

vehicle. Often a joep and cycle are paired

for an assignment the Jeep to creep into

suspected terrain and defend itself if neces.

nary, the “cycle always ready to rip back

to the main body once the enemy has shown

his strength.

“Another special aptitude of the cyclist In

the trick of running Into trouble, doing a

quick turn, akidding to a stop, and going

into action at once with n Tommy gun or

carbine crows the protecting bulwark of

hia machine.

The radio man has an especially vital

Job, serving as the ears of the scouting de-

Wil. A good

operator not only is alert to receive mes-

sages and quick on the transmission, but

will systematically monitor his radio nets

to pick up collateral information about what

is going on at the flanks or with other

scout cars in the net. He also keeps track

of where the car is at any given time, looks

back frequently to orient himself on the

map board, and in an emergency can jump

up to replace one of the gunners.

All cavalry equipment is in a continuous

process of improvement. Thus the six-ton

M3A1 scout car itself, while admittedly a

very handy vehicle, is regarded in the Army

as more or less obsolescent, and it is no

secret that a more modern combat car will

soon take its place, endowed with heavier

armor, greater fire power, and superior

ground-covering qualities. If the old scout

car had a real fault, it was in lacking versa-

tility and power across country. Our com-

manders hate nothing worse than the spec-

tacle of U.S. Army units getting “road-

bound” and unable to move across fields

and intervening terrain to strike back on a

road beyond enemy blocks.

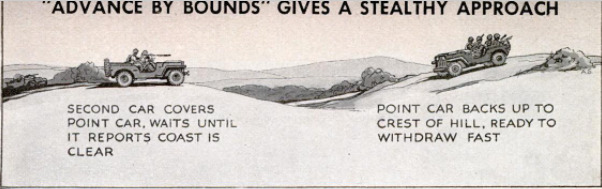

Elementary in the new cavalry technique

is the “advance by bounds,” in which one

car studies the terrain ahead, and then

rushes at full speed to the next covered

point—a hill crest or road turn—while the

following car waits to cover its move with

fire. That accomplished, the section makes

another bound ahead, accommodating its

maneuvers always to the terrain in which

it is operating.

In dangerous territory, Where the road

is broken and enemy resistance may be en-

countered at any point, the cars may turn

around in the road and back up to the

danger point, thus bringing heavy fire power

to bear over the peak of a hill and main-

taining themselves in position to withdraw

swiftly from a hot spot.

When reconnoitering a village or enemy

camp, the cavalrymen try to do their ob-

servation from the extreme flank or rear.

If an ambush is suspected on a road ahead,

they again prefer the safe method of dis-

mounted reconnaissance from the flank, but

if time is pressing they will switch tactics

and send a car in to slash through while

other vehicles cover the suspected zones

with fire.

More complex operations are not ready

for public discussion now. It should be

enough to set down for the record that the

American cavalryman is a tough hombre on

wheels today—he already was tough!

-

Autore secondario

-

John H. Walker (Article Writer)

-

William W. Morris (Photographer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1943-05

-

pagine

-

49-52, 208

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google Digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)